A Catholic history of speaking in tongues from the first Pentecost until the rule of Pope Benedict the XIV, 1748 AD.

The following are the results of a detailed study of early church, medieval and later medieval Catholic writers through seventeen-centuries of church life.

The results are from the Gift of Tongues Project which had a fourfold purpose to:

- uncover new or forgotten ancient literature on the subject

- provide the original source texts in digital format

- translate the texts into English and add some commentary

- to trace the perception of tongues in the church from inception until modern times.

Table of Contents

- A Pictorial Essay on the Catholic history of Speaking in Tongues

- A short Observation on Pentecostal Tongues

- The Doctrine of Tongues from the First to Third-Century

- The Golden Age of the Christian Doctrine of Tongues: the Fourth-Century

- The Connection between Babel and Pentecost

- Hebrew as the First Language of Mankind and of Pentecost

- Pentecost as a Temporary Phenomenon

- Augustine on Tongues Transforming into a Corporate Identity

- Gregory of Nyssa and the One Voice Many Sounds Theory

- Gregory Nazianzus on the Miracle of Speech vs. the Miracle of Hearing

- The Expansion of the Christian Doctrine of Tongues from the Tenth to Sixteenth-Centuries

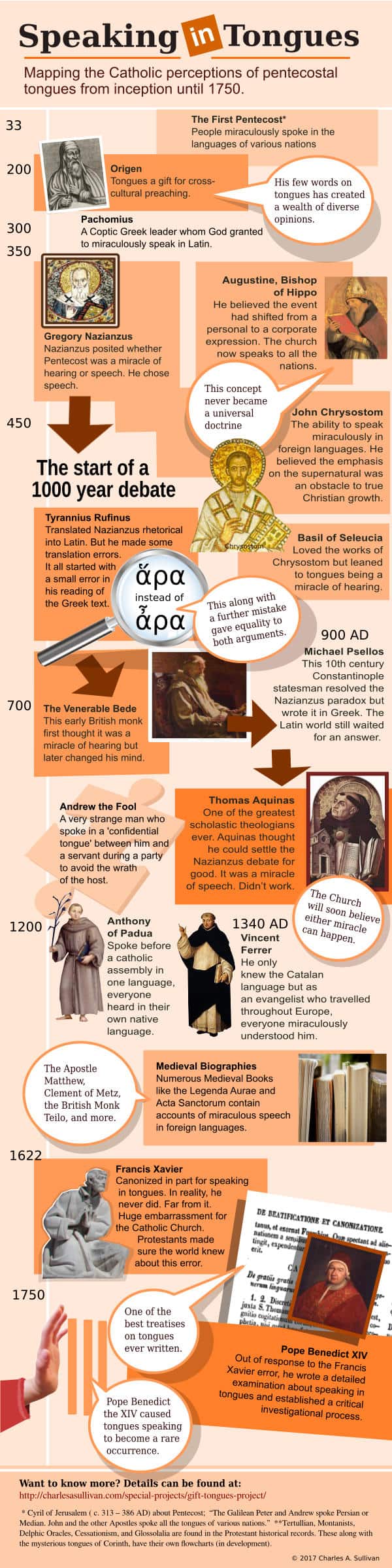

A Pictorial Essay on the Catholic History of Speaking in Tongues

The graphic below assists the reader in quickly understanding the passing tradition of speaking in tongues throughout the centuries in the Catholic Church. The rest of the document will describe these findings. Click on the links throughout this document for more details, or go directly to the Gift of Tongues Project for actual source texts.

A Short Observation on Pentecostal tongues

The large corpus of material studied and compared demonstrates a pattern. The Christian doctrine of tongues was related to human languages for almost 1800 years. The mechanics of how this happened differed. There were perceptions of it being a miracle of speech, hearing, or both. There were no references to angelic speech, prayer language, glossolalia, or ecstatic utterances until the nineteenth-century. The coverage of glossolalia is in Part 2 of this series.

As described by the writer Luke in the first part of the Book of Acts, the address of the Pentecost event in ecclesiastical literature has far more coverage than Paul’s address to speaking in tongues. There is a division between the ancient authors on the theological symbolism of Pentecost. They understood Pentecost in two ways: a symbol of the Gospel becoming a universal message beyond the Jewish community’s boundaries and/or for the Jewish nation to repent.

The focus of this summary is the nature and mechanics behind speaking in tongues. The exploration of tongues as a theological symbol are throughout the source texts documented in the Gift of Tongues Project.

The Doctrine of Tongues from the First to Third-Century

The first Pentecost happened somewhere between 29 and 33 AD, depending on which tradition one chooses to date the crucifixion. The event was listed close to the start of an account written by the physician turned writer, Luke. A work that is universally addressed today as the Book of Acts. The Pentecost narrative is very brief. As mentioned in the Introduction, the English version of this text describing the Pentecost miracle contains approximately 206 words. Perhaps 800 if one includes Peter’s sermon. Two hundred six words echoed throughout history have inspired hundreds of millions to ponder and often replicate in their own lives.

The following are the histories of tongues after the first Pentecost. It assumes a thorough knowledge of the Book of Acts. Some understanding of Paul’s references to tongues in his first letter to the Corinthians may help too.

The earlier church writers who lived between the first and third centuries did mention the Christian doctrine of tongues, such as Irenaeous, who stated it was speaking in a foreign language. There was also Tertullian who recognized the continued rite in his church. Nevertheless, they failed to explain anything more than this. Their actual texts offer little information more than an acknowledgment of its existence.

The debate inevitably leads to Origen – one of the most controversial figures on speaking in tongues. Modern theologians, commentators, and writers all over the broad spectrum of Christian studies believe Origen supports their perspective. These various viewpoints have created an Origen full of contradictions.

Origen was a third-century theologian viewed as either one of the greatest early Christian writers ever because of combining an active and humble faith with a deep intellectual inquiry into matters of faith. He was labeled a heretic after his death for his limited view of the Trinity. He lived at a time the Trinity doctrine was in its infancy and not fully developed. His views did not correlate with the later formulation, and he was posthumously condemned. After careful investigation about his coverage on speaking in tongues, Origen hardly commented on it. If one is to conclude with the limited coverage by him, he did not think there was anyone pious enough during his time for this task, and if they were, it would be for cross-cultural preaching.

The Golden Age of the Christian doctrine of Tongues: the Fourth-Century

There is difficulty finding Christian literature from the first to third-centuries on almost any subject, including speaking in tongues. This lack is due to the devastating effects of the Roman emperor Diocletian’s persecutions in the third century. This problem dramatically changes in the fourth century when Christianity becomes a recognized religion, and later the foremost one within the Roman Empire.

The fourth-century began to unfold more critical details on speaking in tongues. Cyril of Jerusalem wrote that Peter and Andrew spoke miraculously in Persian or Median at Pentecost and the other Apostles were imbued with the knowledge of all languages. The founder of the Egyptian Cenobite movement, Pachomius, a native Coptic speaker, was miraculously granted the ability to speak in Latin.

The doctrine of tongues divided into five streams in the fourth-century.

- The first interpretation was the speaking in Hebrew, and the audience heard in their language.

- The second was Pentecost as a temporary phenomenon.

- The third was the one voice many sounds theory formulated by Gregory of Nyssa.

- Fourth, the transition of a personal to a corporate practice represented by Augustine.

- Fifth, and last of all, the tongues paradox proposed by Gregory Nazianzus.

Some may reckon that two more belong here–the cessation of miracles and the Montanists. Both Cessationism and Montanist tongues are perceptions developed during the eighteenth-century and later. These last two theories are covered in separate articles found at the Gift of Tongues webpage.

Before winding down the path of the five explanations, it is necessary to take a quick look at the confusion of tongues found in the Book of Genesis. This story has an essential relationship with the discussions to follow.

The Connection between Babel and Pentecost

One would assume that the reversal of Babel would be one of the earliest streams of thinking about Pentecost. This proposition is surprisingly, not the case. The idea that the ancient Christian writers would connect the confusion of languages symbolized by the city Babel in the book of Genesis with Pentecost seems logical. The book of Genesis, the first book of the Bible, has a brief narrative that described how humankind originally had one language. This oneness changed with their determination to build a tower to reach into the heavens. This act was unsuccessful by introducing a plurality of languages. Although the text lacks details, the text suggests some form of arrogance and self-determination apart from God. The tower also represented humanity’s ability to do great evil collectively. In response, God chose to divide the one language into many languages and scatter humanity throughout the earth to curb this amassing of power. The overall traditional record does not associate Pentecost as a reversal of Babel.

The connection between God giving Moses’s commandments on Mt. Sinai would appear to be the better correlation. God spoke to Moses directly and established a religious and world order. The Talmud states that God spoke this to Moses in 72 languages – a number understood symbolically as all the world’s languages.

When the Pentecost occurred in the Book of Acts, the apostles and 120 more miraculously spoke in a whole host of languages. The event was the establishment of a new religious and world order that built upon what happened at Mt. Sinai.

The Jewish community today annually celebrates the giving of the law of Moses and call this day Shevuot, which calculates the same days after Passover as Pentecost does. However, this theory has a significant problem. The Shevuot holiday is not an ancient one and does not trace back to the first-century when the first Pentecost occurred. Luke does not mention a direct connection to Shevuot, and neither do any of the ancient Christian writers.

The Babel allusion prevailed discreetly in later dialogues, especially two concepts. The first one related to which language was the first language of mankind and how that fit into the Pentecost narrative. The second relating to the one voice spoken many languages heard theory. The description of both concepts is provided below.

Hebrew as the first language of humankind and Pentecost

There is a substantial corpus about Hebrew being the first language of humankind within ancient Christian literature. There is also a tiny allusion to Pentecost being the speaking of Hebrew sounds while the audience heard in their language. One must keep in mind that this theory about Pentecost does not flow throughout the seas of Christian thought, only in the shadows.

The idea of Hebrew as the first language of humanity starts with the early Christians such as first-century Clement, Bishop of Rome, fourth-century Augustine, Bishop of Hippo, for at least part of his life (He changed his position later). Fourth-century Gregory of Nyssa repudiated the concept of Hebrew as the original language of humanity. The concept was endorsed again by the eighth-century historian and theologian, the Venerable Bede. In the tenth-century Oecumenius, Bishop of Trikka believed that Hebrew was a divine language because when the Lord spoke to Paul on the road to Damascus, it was in Hebrew.

The eleventh-century philosopher-theologian, Michael Psellos, referred to an ideology that placed Hebrew as the first language. He alluded that Pentecost potentially were the speakers vocalizing in Hebrew while the audience heard it in their language. This idea was a hypothesis, not a position he endorsed. Thomas Aquinas too mentioned this explanation but quickly moved onto better, more rational theories.

The speaking of Hebrew sounds and the audience hearing in their language was a small theory that never gained widespread attention. The doctrine never became a standard one with a vibrant local or international appeal.

See Hebrew and the First Language of Mankind for more information.

Pentecost as a Temporary Phenomenon

A text loosely attributed to the fifth-century Pope of Alexandria, Egypt, Cyril of Alexandria, described Pentecost as the “changing of tongues.” Pentecost was the use of foreign languages at Pentecost as a sign for the Jews. This event was a miraculous endowment, and those that received this blessing in @31 AD continued to have this power throughout their lives, but it did not persist after their generation.

Cyril represented the city of Alexandria at the height of its influence and power throughout Christendom. His biography concludes that he was quarrelsome and violent. There are unsubstantiated claims that he was responsible for the death of the revered mathematician, astronomer, philosopher, and scholar Hypatia. Although his reputation today remains controversial, his earlier stature and his near-universal influence require careful attention on the subject of Pentecost. His ideas of Pentecost may have been an older tradition passed down and reinforced by him. The theory of a temporary miracle restricted to the first generation of Christian leadership is hard to trace a start point. There are not enough ancient texts on the subject to build a historical framework.

However, the theory arose again in the thirteenth-century with no references in-between. The celebrated scholastic writer and mystic, Thomas Aquinas, weighed in on the temporary question. Whenever Aquinas addresses a theological subject, it is worth the time to stop and consider. He brought a broad array of the various Christian traditions, writers, texts, and Scripture into a systematic form of thought. Not only was Aquinas systematic, but also a mystic. The combination of these qualities gives him a high score in covering the doctrine of tongues.

He held a similar position on Pentecost to that of Cyril of Alexandria, though he does not mention him by name. He believed the apostles were equipped with the gift of tongues to bring all people back into unity. It was only a temporary activity that later generations would not need. Later leaders would have access to interpreters, which the first generation did not.

Aquinas’ argument is a good and logical one. Unfortunately, the Christian history of tongues does not align with this conclusion. After Aquinas’ time, numerous perceived cases of the miraculous endowments contradict such a sentiment.

The temporary idea of Pentecost was restricted to this miracle alone. There is no implied idea that this temporality extended to miracles of healing, exorcisms, or other divine interventions.

Augustine on Tongues Transforming into a Corporate Identity

Augustine Bishop of Hippo promoted that the Christian rite of speaking in tongues transferred from a personal to a corporate expression. He espoused this position over his lengthy and complicated battle with the dominant tongues-speaking Donatist movement.

The Donatists were a northern African Christian group, broken off from the official Catholic Church over reasons relating to the persecutions against Christians by edict of Emperor Diocletian in the third century. A controversy erupted in the region after the persecutions abated. There was division over how to handle church leaders who assisted with the secular authorities in the persecutions. This problem became a source of contention, and it conflagrated into questions of church leadership, faith, piety, discipline, and politics. One of the outcomes was a separate church movement called the Donatists. At the height of their popularity, the Donatists statistically outnumbered the traditional Catholic representatives in the North Africa region. At the height, it had over 400 bishops.

The Catholic Church was in a contest against the Donatist claims of being the true church. One of the assertions the Donatist’s provided for their superior claim was their ability to speak in tongues. This declaration forced Augustine to take the Donatists and their tongues doctrine seriously and build a dynamic offense against them.

Augustine’s polemic against the Donatists has generated more data on the Christian doctrine of tongues than any other ancient writer and gives a good lock into perceptions of this rite in the fourth-century.

Augustine attacked the Donatist claim of being the true church in several ways.

- One was through mocking, asking when they laid hands on infants whether they spoke in languages or not.

- Or he stated that the gift had passed. The cessation statement was one of many volleys that he made. This cessation needs further clarification. Augustine meant that the individual endowment of miraculously speaking in foreign languages had ceased from functioning. The corporate expression still remained. It cannot be applied to mean the cessation of miracles, healings, or other divine interventions. Augustine was exclusively referring to the individual speaking in tongues. Nothing more.

- In other words, the individual expression of speaking in tongues changed into a corporate one – the church took over the function of speaking in every language to all the nations.

He described Pentecost as each man speaking in every language.

This transformation from individual to corporate identity was referenced by Thomas Aquinas in the thirteenth-century in his work, Summa Theologica, but built little strength around this theme. He left it as is in one sentence.

There is no question that the semantic range of this experience fell inside the use of foreign languages. Augustine used the term linguis omnium gentium “in the languages of all the nations” on at least 23 occasions, and linguis omnium, speaking “in all languages”. Neither does Augustine quote or refer to the Montanist movement in his works.

The Bishop repeatedly answers the question “If I have received the holy Spirit, why am I not speaking in tongues?” Each time, he has a slightly different read. What did he say? “this was a sign that has been satisfied” — the individual expression has been satisfied. He then offers a more theological slant in his Enarratio In Psalmum, “Why then does the holy Spirit not appear now in all languages? On the contrary, He does appear in all the languages. For at that time, the Church was not yet spread out through the circle of lands, that the organs of Christ were speaking in all the nations. Then it was filled-up into one, with respect to which it was being proclaimed in every one of them. Now the entire body of Christ is speaking in all the languages.”1

One has to be very cautious with Augustine on this topic. He was pitting the Catholic Church as the true one because of its universality. He inferred that the Donatists were not so ordained because of their regionalism. His answers were more polemic than theological.

Augustine’s polemical diatribes against the tongues-speaking Donatists never became a universal doctrine. The individual to the corporate idea has indirect allusions in John Chrysostom and Cyril of Alexandria’s works, but nothing concrete. The concept faded out within a generation, and references to him on the subject by later writers are not very frequent, if at all.

See Augustine on the Tongues of Pentecost: Intro for more information.

Gregory of Nyssa and the One Voice Many Sounds Theory

Gregory of Nyssa represents the beginning of the Christian doctrine of tongues that has echoes even today.

Gregory of Nyssa was a fourth-century Bishop of Nyssa – a small town in the historical region of Cappadocia. In today’s geographical terms, central Turkey. The closest major city of influence to Nyssa was Constantinople, which was one of the most important centers of the world.

This Church Father, along with Gregory Nazianzus and Basil the Great were named together as the Cappadocians. Their influence set the groundwork for Christian thought in the Eastern

Roman Empire. Gregory of Nyssa was an articulate and a deep thinker. He not only drew from Christian sources but built his writings around a Greek philosophical framework.

Gregory sees parallels between Babel and Pentecost on the nature of language but produces different outcomes. In the Pentecost story, he explained it as one sound dividing into languages during transmission that the recipients understood.

Gregory of Nyssa’s homily on Pentecost is a happy one, which began with his reference to Psalm 94:1, Come, let us exalt the Lord and continues throughout with this joyful spirit. He wrote of the divine indwelling in the singular and the output of a single sound multiplying into languages during transmission about speaking in tongues. This emphasis on the singularity may trace to the influence of Plotinus — one of the most revered and influential philosophers of the third-century. Plotinus was not a Christian, but a Greek/Roman/Egyptian philosopher who greatly expanded upon the works of Aristotle and Plato. He emphasized that the one supreme being had no “no division, multiplicity or distinction.” Nyssa strictly adhered to a singularity of expression by God when relating to language. The multiplying of languages happened after the sound was emitted and therefore conforms to this philosophical model. However, Nyssa never mentions Plotinus by name or credits his movement in the writings examined so far, so it is hard to connect. One can only assign Plotinus as a potential influence.

What was the sound that the people imbued with the Holy Spirit were speaking before it multiplied during transmission? Nyssa is not clear. It is not a heavenly or divine language because he believed humanity would be too limited in any capacity to produce such a mode of divine communication. Neither would he understand it to be Hebrew. Maybe it was the first language humanity spoke before Babel, but this is doubtful. Perhaps the people were speaking their own language, and the miracle occurred in transmission. Speaking in their own language is the likeliest possibility. Regardless, Gregory of Nyssa did explain this part of his doctrine.

This theory did not solely rest with Gregory of Nyssa. He may be the first to document this position clearly, but the idea was older. There are remnants of this thought in Origen’s writing (Against Celsus 8:37) – though it is only one unclear but sort of relevant sentence and hard to build a case over.

Augustine, Bishop of Hippo, pokes at this too but is unclear. He mentions on many occasions “one man was speaking in every language” or similar.2 What does this mean? How can one man speak simultaneously in all the languages at the same time? Even if a person sequentially went through 72 languages speaking one short sentence, it would take over ten minutes and would not be considered a miracle – only a simple mnemonic recitation. Augustine did not make any attempt to clarify this statement. He was playing with the one voice many sounds theory in a polemical sense and altered the nuance. The idea shifted to the connection between oneness and unity, which in Latin, are similar in spelling. He wanted to emphasize that those who spoke in tongues do it for the sake of unity. He was arguing anyone who promoted speaking in tongues as a device to divide the church is a fleshly and evil endeavor.

The concept takes us to the fifth-century where Basil of Seleucia, a bishop of Seleucia in a region historically named Isauria – today a south-central Turkish coastal town known as Silifke. Basil of Seleucia followed the literary trail of John Chrysostom. He copied many of his traits, but in the case of Pentecost, he adds the one voice many sounds description.

See An analysis of Gregory of Nyssa on Speaking in Tongues for more information.

Gregory Nazianzus on the Miracle of Speech vs. the Miracle of Hearing

Gregory of Nyssa and Gregory of Nazianzus were acquaintances in real life, perhaps more so because of Gregory of Nyssa’s older brother, Basil the Great. Gregory Nazianzus and Basil the Great had a personal and professional relationship that significantly impacted the church in their dealings with Arianism and the development of the Trinity doctrine. Unfortunately, a lifelong fallout happened between Gregory Nazianzus and Basil the Great.3 This tension has little bearing with the topic at hand but builds a small portrait surrounding the key figures of the fourth-century who discuss the doctrine of tongues.

Gregory Nazianzus recognized the theory of a one sound emanating and multiplying during transmission into real languages. He seriously looked at this solution and compared to the miracle of speaking in foreign languages. He found the one sound theory lacking and believed the miracle of speech was the proper interpretation. Perhaps, Nazianzus had a personal objection to Nyssa or a professional one based on research. There are no writings between Nyssa or Nazianzus that allude to a contested difference between them on the subject. The one sound theory never did vanish; only the attachment of Nyssa’s name disappeared. These two positions by Nyssa and Nazianzus set the stage for an ongoing debate for almost two millennia.

Who is Gregory Nazianzus? Most people have not heard of him before, but his contributions to the Christian faith are many. This fourth-century Bishop of Constantinople’s mastery of the Greek language and culture is exquisite and hard to translate into English. His works come across as dry and esoteric in an English translation, whereas in the Greek, he is a well-spring of deep thought. Many church leaders during his period preached and then later published the speech as a homily. Nazianzus likely wrote first and preached later. His works do not come across as great sermons but great works of writing. All these factors have contributed to him being relatively obscure in the annals of Christian history – even though in the fourth-century, he was on the same level of prestige as Augustine or John Chrysostom.

The description of Pentecost as either a miracle of speaking or hearing became the focal point of Gregory Nazianzus in the fourth century when he wrote in one of his Orations that these both were potential possibilities, though he believed Pentecost as a miracle of speech.

Unfortunately, a Latin translator, Tyrannius Rufinus, misunderstood some finer points of Greek grammar when translating and removed Gregory’s preference of it being a miracle of speech and left both as equal possibilities. The majority of Western church leaders were unfamiliar with Greek and relied on Tyrannius’ Latin text. Tyrannius’ mistake created a thousand-year debate of the miracle being one of either speaking or hearing.

See Gregory Nazianzus on the doctrine of tongues intro for more information

The speech versus hearing argument was brought up again in the seventh-century by the Venerable Bede, who wrote two commentaries on Acts. The Venerable Bede lived in the kingdom of the Northumbrians (Northern England. South-East Scotland). He was brilliant in so many areas. Astronomy, mathematics, poetry, music, and literature were some of his many passions. His writing is very engaging and fluid – a good read. His Ecclesiastical History of the English People makes him the earliest authority of English history.

His first commentary delved deeply into the debate, and while studying only the Latin texts, concluded it was a miracle of hearing. In his second commentary, he changed his mind. He alluded Pentecost was a miracle of speech and conjectures it could have been both a miracle of speaking and hearing. He briefly wrote that either interpretation did not matter to him. Perhaps he took this conclusion to avoid saying he was initially wrong.

Another noteworthy discussion about the Nazianzus paradox was presented by Michael Psellos in the eleventh-century. His biography is not one of the religious cloth, but civic politics. His highest position was that of Secretary of State in the highly influential Byzantine City of Constantinople. He was a Christian who had a love-hate relationship with the church. One of the lower moments in that relationship was his choosing Plato over Aristotle. The church tolerated the non-christian writings of Aristotle but frowned on Plato. Psellos studied theology but loved philosophy, and this was a continued source of contention.

His intricate weave of Greek philosophy and Christian faith in a very conservative Christian environment surprisingly did not get him into more serious trouble. He was way ahead of his time. His approach to faith, Scripture, and intellect took western society five hundred or more years to catch-up.

Michael Psellos was caught between two very distinct periods. He lived in the eleventh-century and still was connected to the ancient traditions of the church. He was also at the shift of intellectual and scholarly thought. He bridged both worlds. These conditions are why his work is so important.

He thought highly of his opinions and liked to show-off his intellectual genius. After reading his text, it is not clear whether he was trying to solve the riddle of Nazianzus’ miracle of hearing or speech, or it was an opportunity to show his intellectual mastery. Regardless of his motives, he leaves us with an abundant wealth of historical literature on speaking in tongues.

What did Psellos write that was so important? Two things. He first clears up the Nazianzus paradox stating that it was a miracle of speaking. Secondly, he notably clarifies the similarities and differences between the ancient Greek prophetesses and the disciples of Christ. The prophetesses went into a frenzy and spontaneously spoke in foreign languages they did not know beforehand. The Apostles did not go in a frenzy but did spontaneously speak in foreign languages.

Psellos had detailed knowledge of the pagan Greek prophets and explained that the ancient female prophets of Phoebe would go frenzy state and speak in foreign languages. This explanation is a very early and essential contribution to the modern tongues debate because there is a connection given to the ancient Greek prophets going into ecstasy and producing ecstatic speech with Pentecost within modern academia. The theory proceeds to believe Pentecost and related experiences a synergism of the ancient Greek practice of ecstatic speech to make the Christian faith a universal one.

Psellos may be the oldest commentator on the subject of the Greek prophetesses, and his conclusions require significant consideration. His knowledge of ancient Greek philosophy and religion is unparalleled even by modern standards. It is also seven hundred years older than most works that address the relationship between the Christian event and the pagan Greek rite.

He described that the Pentecostal speakers spoke with total comprehension and detailed how it worked. The apostles thought process remained untouched, but when attempting to speak, their lips were divinely inspired. The speaker could change the language at any given moment, depending on what language group the surrounding audience possessed. He thought this action a miracle of speech and sided with Nazianzus.

The total control of one’s mind while under the divine influence differentiated the Christian event from the pagan one. As Psellos went on to describe, the Greek prophetesses did not have any control over what they were saying. There was a complete cognitive disassociation between their mind and their speech while the Apostles had complete mastery over theirs.

Last, Psellos introduces a concept of tongues-speaking correlated with pharmacology. He described the Hellenic world using plants to arrive in a state of divine ecstasy. His text infers the primary purpose was in the art of healing. His writing is somewhat unclear at this point, but there was a relationship between the two. Perhaps tongues-speaking practiced by the ancient Greeks was part of the ancient rite of healing. It is hard to be definitive with this because his writing style here is obscure. He warns to stay away from the use of exotic things that assist in going into a state of divine ecstasy.

Thomas Aquinas tried to conclude the tongues as speech or hearing debate. Aquinas proceeded to use his argument and objection method for examining the Nazianzus paradox. In the end, he clearly stated it was a miracle of speech. His coverage was well done. However, this attempt was not successful in quelling the controversy.

Another aspect that Aquinas introduced was the relationship between the office of tongues and prophecy. The topic has lurked as early as the fourth-century but never in the forefront. Aquinas put the topic as a priority. Given that he was a mystic and lived in a world that heavily emphasized the supernatural, this comes as no surprise. He believed that the gift of tongues was simply a systematic procedure of speaking and translating one language into another. The process required no critical thinking, spiritual illumination, or comprehension of the overall narrative. He believed the agency of prophecy possessed the means for translating and interpreting but added another vital asset – critical thinking. One must be cognizant of the fact that his idea of critical thinking is slightly different from ours. He includes spiritual illumination along with intellectual acuity as a formula for critical thinking. The prophetic person could understand the meaning behind the speech and how it applied to one’s daily life. Therefore, he felt prophecy was a much better and superior office than merely speaking and translating.

The Expansion of the Christian Doctrine of Tongues from the Tenth to Eighteenth-Centuries

The tenth to sixteenth-centuries could be held as the golden age of tongues-speaking in the Catholic Church, and arguably the most significant era for the Christian doctrine of tongues. The next two-hundred years that reached into the eighteenth-century was the civil war that raged between Protestants and Catholics that put miracles, including speaking in tongues, in the epicenter. These eight-centuries were the era of super -supernaturalism in almost every area of human life. Speaking in tongues was common and attached to a variety of celebrity saints – from Andrew the Fool in the tenth to Francis Xavier in the sixteenth. This period had established the doctrine of tongues as a miracle of hearing, speaking, or a combination of both.

Later Medieval Accounts of Speaking in Tongues

There are numerous examples. The later legend of the thirteenth-century had Anthony of Padua, a popular speaker in his time, spoke in the language of the Spirit to a mixed ethnic and linguistic gathering of Catholic authorities who heard him in their language. What was the language of the Spirit? This term was never clarified in the text or by any other author and a mystery.

In the fourteenth-century, Vincent Ferrer was a well-known evangelist, perhaps in the top 50 in the history of the church. He visited many ethnic and linguistic communities while only knowing his native Valencian language. His orations were so great and powerful that it was alleged people miraculously heard him speak in their language.

There were also revisions by later writers to earlier lives of saints such as Matthew the Apostle, Patiens of Metz in the third, and the sixth-century Welsh saints, David, Padarn, and Teilo. They were claimed to have spoken miraculously in foreign languages.

Speaking in tongues was also wielded as a political tool. The French religious orders, l’abbaye Saint-Clément, and l’abbaye Saint-Arnould had a strong competition between them during the tenth and fourteenth centuries. L’abbaye Saint-Clément proposed their order to be the foremost because their lineage traced back to a highly esteemed and ancient founder. L’abbaye Saint-Arnould countered with St. Patiens, who had the miraculous ability to speak in tongues.

The account of Andrew the Fool has an interesting twist in the annals of speaking in tongues. Andrew the Fool often cited as Andrew of Constantinople, or Andrew Salus was a tenth-century Christian follower known for his unique lifestyle that would be classified under some form of mental illness by today’s standards. However, many biographers believe it was a ruse purposely done by Andrew. There is a rich tradition of holy fools in Eastern Orthodox literature who feigned insanity as a form of a prophetic and teaching device. The story of Andrew the Fool’s miraculous endowment of tongues facilitated a private conversation between Andrew and a slave while attending a party. This miracle allowed them to talk freely without the party’s patron privy to the conversation and becoming angry.

The Legend of Francis Xavier Speaking in Tongues

The sainthood of Francis Xavier in the sixteenth century and the incredulous notion that he miraculously spoke in foreign languages brought the gift of tongues to the forefront of theological controversy. Protestants used his example of how Catholics had become corrupt, to the point of making fictitious accounts that contradict the evidence. A closer look demonstrated that the sainthood investigation process was flawed on the accounts of him speaking in tongues. On the contrary, a proper examination showed that Francis struggled with language acquisition. His sainthood with partial grounds based on speaking in tongues was a later embarrassment to the Society of Jesus to whom Francis belonged. The Society of Jesus is an educational, missionary, and charitable organization within the Catholic church that was ambitiously counter-reformation in its early beginnings. The Society of Jesus still exists today and is the largest single order in the Catholic Church.

The mistaken tongues miracle in Francis’ life also was a headache for the Catholic Church leadership itself. This controversy led to Pope Benedict XIV to write a treatise on the gift of tongues around 1748 and describe what it is, is not, and what criteria to investigate such a claim. He concluded that the gift of tongues could be speaking in foreign languages or a miracle of hearing.

This treatise was a well-written and researched document. No other church leader or religious organization, even the Renewalist movement, have superseded his work that seeks to validate a claim for speaking in tongues. After his publication, the investigation of claims for tongues-speaking in the Catholic Church had significantly declined.

- Augustine. Enarratio in Psalmum. CXLVII:19 (147:19)

- Sermo CLXXV:3 (175:3)

- Frienship in Late Antiquity: The Case of Gregory Nazianzen and Basil the Great

Hi Mr. Sullivan, a well researched article. I learned a great deal. My question. Is there any earlier church writings on tongues as the evidence of receiving the baptism of the Holy Spirit? And are there any writings by earlier Jewish theologians on tongues? Thanks

Tongues as evidence of the baptism of the Holy Spirit is a newer doctrine. The closest earlier equivalent I can arrive at is the Catholic doctrine of ecstasy especially espoused by Theresa of Avila. Some parallels can be found here: https://charlesasullivan.com/4428/thoughts-on-ecstasy-private-revelation-and-prophecy/

In relation to the tongues of Pentecost with Judaism, this was the first avenue I explored before the Gift of Tongues Project started. I submitted a paper in my Intro to Talmud class I took at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem looking for such connections in the 1980s. In the end, I did not find any earlier Jewish writings that parallel such an experience. However, there are strong parallels in Jewish literature and traditions to Paul’s references to the tongues of Corinth. This is part three of the summary which is in development right now.

Sir Professor Sullivan

Thank you very much for such a rich sources and resourses as well .

That is your kindness . Do not forget me please . You are a real miracle

onto my academic life .

Hi read through your article … can you please confirm the books or literature used for your citations… Im working on a Paper for school thank you..

This summary has hyperlinks throughout that you can click on. These links bring you to the detailed accounts and citations you are looking for. If there is a hyperlink missing, then go to the Gift of Tongues Project table of contents. The TOC contains a list of all the ancient authors on the subject mentioned in this article along with commentaries, translation notes, and in most cases, digitized source texts.

Thank you! This is exactly what I’ve been looking for. In your research on tongues, have you come across anything that would support the laying on of hands by laypeople in order to release dormant graces, as with the ritual of baptism in the Holy Spirit? I’ve been trying for years to locate evidence of this practice in the tradition of the Church.

The doctrine of the Baptism of the Holy Spirit is a recent doctrinal addition to the Christian faith. The closest historic parallel is the late Medieval Catholic doctrine of ecstasy. Some introductory information can be found in the following article, Thoughts on Ecstasy, Private Revelation, and Prophecy.

Hope this helps.

Hi Charles,

“However, there are strong parallels in Jewish literature and traditions to Paul’s references to the tongues of Corinth. This is part three of the summary which is in development right now.” Please can you explain ore develop this comment deeper ?

Thank You

There are a number of articles published about Jewish Customs and Corinth since this time found at the Tongues of Corinth section of the Gift of Tongues Project.

“However, there are strong parallels in Jewish literature and traditions to Paul’s references to the tongues of Corinth. This is part three of the summary which is in development right now,” has been removed from the article. This statement was an old one that no longer fits within this text. Thank you for pointing this out.

Charles A. Sullivan

Can you explain what is meant by corporate usage of tongues by Augustine? Was he implying that since the church was across many nations now, that act of “speaking in tongues” was fulfilled in Christians of different nation speaking in their language? Was it that one congregation was multilingual? Or something else?

Also, I’m curious how all of this fits with 1 Cor. 14:13-15. It seems that all of the scripture makes sense that Tongues is a skill to speak an unlearned language, except this passage. Would a person speaking a foreign language be doing so without his mind paying attention?

Augustine believed that the Church had become a universal phenomenon and corporately had the personnel available to speak whatever language was required to fulfil its mission both locally and abroad. A miraculous infusion of speaking a foreign language was no longer necessary.

The early concept of Pentecost does not align with I Corinthians at all. They are two different and distinct entities. An entire section of the Gift of Tongues Project is devoted to understanding I Corinthians from an early Church/Jewish perspective. Paul was not referring to anything miraculous. It was a problem of the ancient Jewish rite of speaking and interpreting inherited by the Corinthian assembly. See https://charlesasullivan.com/gift-tongues-project/#anch12 for more details.

Amazing. Thanks for your efforts. I can’t tell you how much this subject still divides Christians. What the above information shows me is that there is evidence that the Pentecost phenomena did not cease at all.

And, it seems that this gift of language is often miraculous at the hearing end and not by necessity in the speaking. A careful reading of Acts 2 suggests the same. The apostles could hardly have spoken every native language of all those listed, especially given the crowd and the confusion that occurs in such large gatherings. But its clear they did speak “in other languages as the Spirit gave them utterance.”

Dear Mr. Sullivan, Your #3 comment to encourage to learn ancient languages REVEALS you have a COMPLETE MISUNDERSTANDING of that Biblical Truth.

On the day of Pentecost those filled to OVERFLOWING WITH GOD’s HOLY SPIRIT, SPOKE in languages they had NOT learned.

They were empowered/unctioned by GOD’s HOLY SPIRIT to speak languages they had never learned. Verified on other occasions following that day.

Of course to BELIEVE that is true, one must believe in GOD ADONAI/JEHOVAH and that GOD is all knowing and all powerful, that GOD deals in the supernatural.

On the surface, it appears you have relegated speaking in tongues to the natural realm, denying the supernatural element.

Just as GOD supernaturally gave messages to HIS Prophets down through the ages; GOD has fulfilled HIS PROMISE to send the INTERCESSOR HOLY SPIRIT who prays through individuals in languages not learned, gives messages, and acts kn behalf of and for human needs to be supplied, speaks wisdom, knowledge, revelation/insight, Gives understanding and many supernatural comfort etc.

Seek GOD for HIS FULNESS and

– if you will allow HOLY SPIRIT to HE will pray/speak through you;

– If you have accepted the fact/ BELIEVED that JESUS is GOD, came in the flesh, died/shed HIS BLOOD as our sacrifice and asked JESUS/MESSIAH to become your personal SAVIOUR, YESHUA MESSIAH will come into your heart/spirit.

HOLY SPIRIT will impart the SPIRIT of CHRIST into your LIFE. When HOLY SPIRIT lives WITHIN a person if we ask HIM and then allow HOLY SPIRIT, HE will speak through us by HIS MIRACULOUS POWER. That us called Speaking in Tongues.

Sent from my iPhone

Yes, you are correct that ancient Church tradition understands it was the divine ability to miraculously speak a foreign language unknown beforehand by the speaker. Perhaps I did not emphasize that enough. Thank you for your response.

Thankyou Mr. Sullivan, very well researced and informative article on tracing the history of the phenomenon of Tongues. I was preparing a sermon on this, and was looking for evidence through Church history.