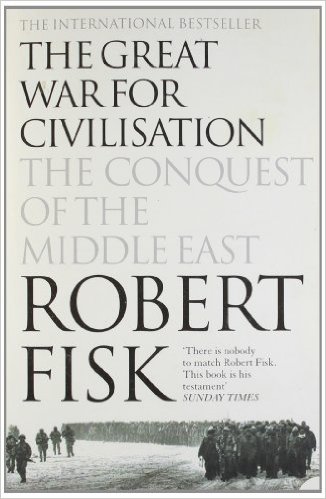

The Great War for Civilisation: The Conquest of the Middle East by the seasoned author and journalist, Robert Fisk is a compilation of his over 30 years of on-field experiences in the various war zones around the Mediterranean and Middle East. The result is comprehensive portrait from a litany of primary sources that makes this book a definitive work.

This work is difficult, challenging and long, but worth every word. One cannot read this in one, or even two sittings. Nor can it be read for great lengths of time because the dark corners of humanity are ever present in this book. Such imagery requires one to pause repeatedly and escape from such realities.

Fisk purposely over-documented The Great War for Civilisation. There is no other choice for the author to do this as detractors, especially those of government, military and enforcement institutions, would like to refute such findings and discredit him personally. The greatest strength of his book is the documentation that takes it out of the realm of his personal opinion and into the place of factual history. It is a work that has been sorely lacking in this genre.

This is not a book for those who like clichés or black and white answers. Fisk avoids both which causes the reader to wonder initially if one ever will arrive at a some conclusion amid the vast amount of information he uncovers. He seldom takes enough time to reflect or philosophize about the lessons learned from all these experiences. It is a constant barrage of facts with few references connecting these behaviors into a larger narrative. The lack in this area may be why he has succeeded in fact finding so long. Trying to figure it out would invite cynicism and throwing in the white towel.

The book has a liberal dose of history throughout but is not history for the sake of history. It is the necessary building of a plot to explain the present.

The following quote is one of his few philosophical moments in the book:

Soldier and civilian, they died in their tens of thousands because death has been concocted for them, morality hitched like a halter round the warhorse so that we could talk about ‘target-rich environments’ and ‘collateral damage’ – that most infantile of attempts to shake off the crime of killing – and report the victory parades, the tearing down of statues and the importance of peace.

Governments like it that way. They want their people to see war as a drama of opposites, good and evil, ‘them’ and ‘us’, victory or defeat. However, war is primarily not about victory or defeat but death and the infliction of death. It represents the total failure of the human spirit. [Pg. XIX]

Humanity and inhumanity is the core of his observations and message. He finds inhumanity everywhere in the vestibules of power that he has observed. It is found in the semantics where ‘collateral damage’ is replaced for the killing of innocent civilians. It is in attaching the word ‘terrorist’ to enemies of a state which strips them of human status and consequently these people can be tortured, abused, neglected and discarded without any rights.[Pg. 464] Over and over again, Fisk brings names to those who have been or are key characters in the conflict. He constantly refers to the regular person off the street who suffered or died as a result of the inhumanities involuntarily forced upon them. He does not restrict this analysis to a few despots or exceptions; it is found in almost every political entity involved in the Middle East.

He has a strong criticism towards Israel’s Prime Minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, who sees Palestinians a people who cannot manage their affairs and in need of an overseer such as Israel. [Pg. 535] He is highly critical of George Bush’s war on terror, and even harsher tones for Bush’s Secretary of Defense, Donald Rumsfeld; who at one time was on good terms with Saddam Hussein. He derided President Clinton for using Iraq as a prop to deflect the Monica Lewinsky affair, and Tony Blair, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom at the time, also falls under his critical scrutiny. Saddam Hussein painted as an evil despot, and Yasser Arafat, as a defeated warrior who made too many compromises at the Oslo accords. No government leader, opposition, or foreign policy comes out looking right under his critical microscope. The only signs of mercy shown are his portraits of everyday people.

The overarching narrative is rarely directly addressed. It leaves readers to fill in the blanks. What do his experiences about all these conflicts have in common? Fisk would likely say it started with Western European colonialism that improperly sliced-up the Ottoman Empire.

A narrative begins to appear a third of the way in the book when he covers the massive detainment, torture, executions and rapings of Algerians sponsored by the Algerian government in the early 1990s. A conflict that was a tit-for-tat tussle between government and reactionist forces, prompting an unending cycle of provocation and retribution resulting in the loss of untold innocent civilian lives. This cycle of provocation is a thesis throughout the book applied to almost every other conflict. These governments or despots have appeased their American sponsors and avoided world scrutiny by terming their behavior as a war on ‘terrorism’. Terrorism is an arbitrary word at the best of times and often left for the lowest members of police or security forces to define.

Torture and execution become a staple diet within the confines of the book because of this.

He demonstrates the double-sided American policy with the Armenian Genocide. An event where the U.S. government has agreed to call the slaughter of a complete ethnic group by the Turks as a dispute rather than genocide to secure good relations with Turkey. Fisk displays here the U.S. government putting political aims more important than truth.

He firmly believes one of the greatest errors of the United States foreign policy is ignoring the United Nations resolution 242. A text that calls for the nation of Israel to return to their pre-1967 borders. The resolution allows forced-out Palestinians back to their land; a land that was annexed by Israel after the 1967 war. A matter no longer referenced as occupied territory by the United States, but as ‘territories in dispute’. A semantic which gives Israel more credence for ownership.[Pg. 539] Fisk believes that Israel’s acceptance of 242 would be a strong step for peace in the Middle East but finds it unattainable in the Israeli psyche. It is so far from the Israeli mindset that when he conversed with a young Israeli immigration officer she did not even know that the resolution existed.[Pg. 550]

The 1991 liberation of Kuwait, and the 2003 war on Iraq move strengthens his thesis. The United States singular desire to take down Saddam Hussein at the expense of the civilian population paid a hefty future price of disrespect. The severe sanctions against any imported items into Iraq after the liberation of Kuwait was an act of inhumanity according to Fisk. He details the problem of much needed medical supplies for hospitals badly required for treating the higher than the average number of children acquiring leukemia. A condition that is much greater than world standards and arguably through contact with depleted uranium shells used by the American and British forces. The American administration would not allow for import of these medicines for fear that they convert them for weapons of mass destruction. Fisk himself performed a donation drive in Britain, convincing both the Americans and Iraqi Government to the rightness of his cause, and personally delivered medical supplies to these children in several Iraqi hospitals.

The semantics is found in the words collateral damage. Fisk documents the cluster bombs being thrust on civilian populations and indiscriminate bombings of civilian homes to which the American Government never apologized. The U.S. simply stated that this was collateral damage. A term that dehumanized and ignored the innocent victims. This arrogant behavior intensified the anger within the Iraqi populace. He puts the reader into a paradox. If the United States was only interested in taking down Saddam and his regime why were the average citizens of Iraq being punished? The Iraqis felt like the overthrow of one regime was simply supplanted by another foreign one that didn’t care about their welfare at all. Worst of all, a non-Muslim one. These sanctions fostered a negative reaction to the West. Fisk chose to quote Margaret Hassan, a British woman married to an Iraqi, and who also who ran the CARE office in Baghdad, on how negative the sentiment was;

They think that we will be so broken, so shattered by this suffering that we will do anything – even give our lives – to get rid of Saddam. The uprising against the Baath party failed in 1991, so now they are using cruder methods. But they are wrong. These people have been reduced to penury. They live in shit. And you have no money and no food, you don’t worry about democracy or who your leaders are.[Pg. 867]

There are some references to religious conflict between Muslim and Christians, Muslim vs. Muslim, and Muslim vs. secular Muslim, but this is mostly tertiary according to Fisk. He believes these are internal and foreign government policy failures expressed in the brutality, executions, and torture. These have fomented a great part of the current Middle-Eastern scenario today. This leads the reader to think that the failure of government and international communities to bring about justice and root out brutality has led many civilians and organizations to turn to Islam as a better alternative.

Fisk does not believe religion is the most important catalyst in these conflicts. There are two exceptions to this which are traced to the U.S. and Britain’s participation in the liberation of Kuwait. The first one relates to the military staging area of Saudi Arabia which contains the two holiest places of the Muslim religion; Mecca and Medina. The Americans and the British, perceived as Christian nations, underestimated the religious backlash of militarily building up a strong presence in Saudi Arabia. Fisk quoted Ali Mahmoud, the Associated Press chief in Bahrain, to explain this repercussion which now appears prophetic, “The fact that the theocratic and nationalist regimes have invited the United States to the Middle East will long be resented and never will be condoned. When the crisis is over, [Iraq’s invasion into Kuwait] the worst is yet to come.” [Pg. 725] The Western Christian forces should never have assembled in Saudi Arabia.

The second one was in promoting an insurrection in Iraq during the 1991 war. George Bush authorized the broadcast and air-dropping of millions of leaflets in Iraq, encouraging the Iraqi people to overthrow Saddam and his regime. An act that prompted the Shia Muslim minority in the south, and the Kurds in the north, to rebel. It was a strategy that ended in a bloody response by the Iraqi Republican Guard while the U.S. stood aside and did nothing to protect them. Both these groups, especially the Shiite Muslims felt betrayed.

These injustices to the Arab peoples throughout the Middle East were expressed in the destruction in the World Trade Centers in New York which Fisk believed, “represented not just a terrible crime but a terrible failure, the collapse of decades of maimed, hopeless, selfish policies in the Middle East, which we would at last recognize – if we were wise – or which, more likely, we would now bury beneath the rubble of New York, an undiscussible subject whose mere mention would indicate support for America’s enemies”, [Pg. 1027] and then further added, “No, Israel was not blame for what happened on September 11th, 2001. The culprit were Arabs, not Israelis. But America’s failure to act with honour in the Middle East, its promiscuous sale of missiles to those who use them against civilians, its blithe disregard for the deaths of tens of thousands of Iraqi children under sanctions of which Washington was the principal supporter – all these were intimately related to the society that produced Arabs who plunged New York into an apocalypse of fire.”[Pg. 1037]

After reading the book, and spending a considerable amount of time reviewing his videos, he does not have a political agenda. His purpose follows the historical pillars of journalism. He believes that the role of a journalist is to “challenge authority – all authority – especially so when governments and politicians take us to war, when they have decided that they will kill and others will die.” [Pg. XXIII] His task is to uncover truth, and convey it to the public – a truth that is often purposely obscured, misappropriated, or spun by those who possess such power to tell.

Fisk is sprinting to get this message out about Arab injustice and how to rectify it. It may also be a form of catharsis for him.

I haven’t read a historical account that takes in such a comprehensive listing of forces, influences, corruption, power and revolt since Josephus’ War on the Jews written almost 2000 years ago. The geographic location is almost the same, with Rome being replaced by the United States. It is a repeat of a similar story.

This book answers for me one of the most difficult questions that I have asked for almost thirty years, who are the Arabs, and why are they so angry?

This work explains the Middle Eastern psyche for the Western reader without spin from either a religious or government perspective. Such coverage is a rarity.

The Great War for Civilisation: The Conquest of the Middle East, by Robert Fisk, answers that question in great detail, and much more. The book has an incredible amount of information about the Arab world, its psyche, and their place in the Middle East. He also focuses on the universal problems of war, corruption, lies, betrayal, and deceits. His historical record is fresh and is not the same as the typical Western accounts eschewed by Governments and pundits. In fact, he expansively wrote to rewrite history properly without the spin that is considerably different.

One thing he leaves out entirely, and maybe purposely is the role of corruption in this whole process. A factor that may be too subjective that cannot be so easily documented or proven, except on petty levels with taxis or lower government agents.

There is so much more that I would write about Fisk’s book, but it overruns the limit for standard book reviews.

If anyone wants to think about or understand the Middle East, this should be one of the primary source books for the Western reader. It is mandatory reading for anyone interested in this genre.

—————-

For further reading see :

Hello Charles

You have convinced me through your review that I need to read this book!! I have spent time with an Iraqi women and her hatred of the US was daunting. It’s a wonder why she even relocated to the states.

Perhaps this book will help me understand the Iraqi perspective in a more wholistic way.

Thanks for this review.

Linda

Mistake 1 An expanding Jewish national state in an Arab Muslim region

Mistake 2 Expanding Muslim migrants into western societies

Mistake 3 Attacking Muslim societies on behalf of the Jewish national state

Mistake 4 Antagonising Muslim immigrants in western societies

Mistake 5 Expanding “antisemitism” to mean disagreement with Netanyahu and his quotation of I Samuel 15.3

Mistake 6 Planning the extermination of Iran, Lebanon, Syria, West Bank, &c

Not 2 or 4 mistakes but 6.

Alison Weir, Stephen Sizer, Norman Finkelstein, Omer Bartov – all “antisemites”….!