Gregory of Nyssa on divine speech, human languages, and Pentecost.

Gregory of Nyssa, along with Augustine, Bishop of Hippo, and Gregory Nazianzus, set the framework for the christian doctrine of tongues from the fourth-century and onwards. Although there are other narratives during this period such as John Chrysostom, Cyril of Alexandria, Cyril of Jerusalem, and Pachomius, these did not have the future impact on this doctrine as the above three accomplished.

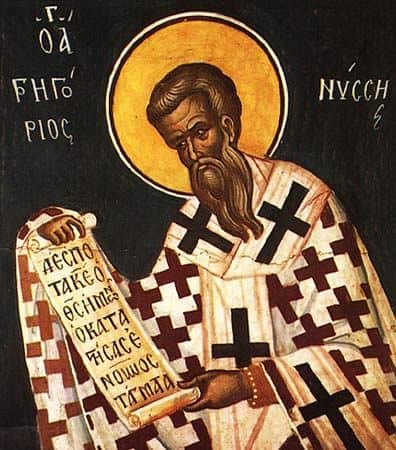

The focus of this article is on Gregory of Nyssa. His name is hardly known, if at all, in chapels, streets, or coffee shops today, but in his time, he was a powerful writer, speaker, and teacher. His influence was widespread throughout all Christendom.

Gregory of Nyssa was a fourth-century Bishop of Nyssa – a small town in the historic region of Cappadocia. In today’s geographical terms, central Turkey. The closest major city of influence to Nyssa was Constantinople – which at the time was one of the most influential centers of the world.

Gregory of Nyssa, along with Gregory Nazianzus and Basil the Great were named together as the Cappadocians. Their influence set the groundwork for christian thought in the Eastern Roman Empire. Gregory of Nyssa was an articulate and a deep thinker. He not only drew from christian sources, but built his writings around a Greek philosophical framework.

His theory of divine speech and human languages demonstrate an important perspective in the history of the christian doctrine of tongues.

Nyssa’s idea of divine and human language

Gregory wrote a detailed treaty against a man named Eunomius who had a large following in the christian community, but in matters of theology slightly changed some constants that better suited his philosophy of god and life. There were many subtle shifts that go beyond this study. However, the controversy brings to light Gregory’s views of speaking in tongues.

Eunomius brought up the question whether God spoke in human language, specifically the Hebrew language. Gregory answered by building his thesis around the confusion of languages written in the Book of Genesis. His observations gave a number of valuable thoughts. The first one being that language is a human invention allowed to grow and develop, and that God Himself does not speak in human language as His normal mode of communication.

As he wrote in Contra Eunomium:

So that our position remains unshaken, that human language is the invention of the human mind or understanding. For from the beginning, as long as all men had the same language, we see from Holy Scripture that men received no teaching of God’s words, nor, when men were separated into various differences of language, did a Divine enactment prescribe how each man should talk. But God, willing that men should speak different languages, gave human nature full liberty to formulate arbitrary sounds, so as to render their meaning more intelligible.1

Whenever Gregory referred to God speaking, he left the word ambiguous in Greek as voice (phônos — φῶνος).

The avid reader may find that the English translation of the treatise Contra Eunomium found in the Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church second series does not prove this theory. This is a problem of the English translation which in other areas is a good one, but fails when it comes to differentiating between the Greek nouns, glossa which is the noun for language and phonos which means sound or voice (γλῶσσα and φῶνος).

Secondly, Gregory believed that there was only one language before the confusion of languages at Babel. What exactly this language was, he does not know. He left this one ambiguous too, using voice again, rather than language in the majority of occasions, especially highlighted in this key passage “μιᾷ συνέζων φωνῇ πάντων ἀνθρώπων τὸ πλήρωμα,” “the aggregate of men dwelt together with one voice among them.” The word here for voice is φωνῇ not language as the original English translation of this text provided.2

He did not believe man’s original language was the language of God because God did not use human language as the basis of His natural way of communicating. He refuted the idea that Hebrew was first original one because it was not the most ancient of languages.

But some who have carefully studied the Scriptures tell us that the Hebrew tongue is not even ancient like the others. . .3

Nyssa’s idea of Pentecost

Gregory does not make the Pentecostal event related in the Book of Acts as a reversal of Babel. Instead, he sees parallels between the two stories on the nature of language with different outcomes. In the Pentecost story, he explained it as one sound dividing into languages during transmission that the recipients understood.

For at the river Jordan, after the descent of the Holy Ghost, and again in the hearing of the Jews, and at the Transfiguration, there came a voice from heaven, teaching men not only to regard the phenomenon as something more than a figure, but also to believe the beloved Son of God to be truly God. Now that voice was fashioned by God, suitably to the understanding of the hearers, in airy substance, and adapted to the language of the day, God, “who willeth that all men should be saved and come to the knowledge of the truth.”4 5

Gregory believed the sound of God speaking at in the events of Jesus’ baptism, and the transfiguration was not a language, rather, it was a sound that had the ability to adapt during transmission into a targeted human language.

Now when one reads his accounts of Pentecost, this same formula is found with those imbued with the fiery tongues.

In his treatise Contra Eunomium he wrote:

We have read about this in Acts, that the sounds were being divided into many according to the power of God, so then no one would be bereft of their language.6 7 8

And then again in his homily De Spiritu Sancto sive in Pentecosten:

Consequently, the narrative of the Book of Acts says that while these people are gathered in the upper room, is the dividing up in each one the pure and supernatural fire in the form of languages according to the number of disciples.

So then these people are thus discoursing in Parthian, Mede, and Elamite in the other remaining nations, adapting their voices with respect to authority to every state language. Even as the Apostle says, “I wish five words to speak with my mind in the Church in order that I may benefit others than a thousand words in a tongue.” Truly at that time the benefit was the same language begotten into foreign languages so that the preaching to those ignorant of the truth would not be in vain when those preaching thwart them by a single voice. Now indeed while existing according to the same sounding language, it is necessary to seek after the fiery tongue of the Spirit for the illumination of those who dwell in darkness through error.9

Gregory of Nyssa’s homily on Pentecost is a happy tome which began with his reference to Psalm 94:1, Come, let us exalt the Lord and continues throughout with this joyful spirit. In reference to speaking in tongues, he wrote of the divine indwelling in the singular and the output of a single sound suggesting a miraculous multiplication into languages during transmission. This emphasis on the singularity may be traced to the influence of Plotinus — one of the most revered and influential philosophers of the third-century. Plotinus was not a christian, but a Greek/Roman/Egyptian philosopher who greatly expanded upon the works of Aristotle and Plato. He emphasized that the one supreme being had no “no division, multiplicity or distinction.”10 Nyssa strictly adhered to a singularity of expression by God when relating to language. The multiplying of languages happened after the sound was emitted and therefore conforms to this philosophical model. However, Nyssa never mentions Plotinus by name or credits his movement in Contra Eunomium so it is hard to make a direct connection. I believe that there is some influence here.

What then was the sound that the people imbued with the Holy Spirit were speaking before it multiplied during transmission? Nyssa is not clear. It is not a heavenly or divine language because he believed man would be too limited in any capacity to produce such a mode of divine communication. Neither would he believe it to be Hebrew. Maybe it was the first language mankind spoke before Babel, but this is doubtful. Perhaps the people were speaking their own language and the miracle occurred in transmission. I think speaking in their own language with a miraculous transmission is the likeliest possibility. Regardless, Gregory of Nyssa was not clear in this part of his doctrine.

The concept of one voice many sounds theory competed with the idea of tongues as a miraculous endowment of one or more foreign languages as the proper theological interpretation of Pentecost. Augustine forwarded the one voice theory as political ammunition against the rival Donatist movement. On other occasions he held to the foreign language one.11 Basil of Seleucia (fifth century) held to the one voice one but slides into foreign languages at the end of his document.12 The Venerable Bede held onto the idea of one voice many sounds in the 8th century, but loosened this stance later on.13

The one voice theory never gained the momentum that the miracle of a foreign language generated over the centuries.

The differing views between Nyssa and Nazianzus on Pentecost

Gregory of Nyssa and Gregory of Nazianzus were acquaintances in real life, perhaps more so because of Gregory of Nyssa’s older brother, Basil the Great. Gregory Nazianzus and Basil the Great had a personal and professional relationship that greatly impacted the church in their dealings with Arianism and the development of the Trinity doctrine. Unfortunately, a fallout happened between Gregory Nazianzus and Basil the Great that never was repaired.14

Gregory Nazianzus recognized the theory of a one sound emanating and multiplying during transmission into real languages. He seriously looked at this solution and posited this against the miracle of speaking in foreign languages. He found the one sound theory lacking and believed the miracle of speech was the proper interpretation. Perhaps this is a personal objection to Nyssa or a professional one based on research. There are no writings between Nyssa or Nazianzus that allude to a contested difference between them on the subject. Nyssa’s contribution to the christian doctrine of tongues has long been forgotten in the annals of history, but Nazianzus has survived. On the other hand, the theory itself posited by Nyssa never did vanish. These two positions by Nyssa and Nazianzus set the stage for an ongoing debate for almost 900 years.

- NPNF2-05. Gregory of Nyssa Pg. 276

- See NPNF2-05. Gregory of Nyssa Pg. 276 for the full text

- NPNF2-05. Gregory of Nyssa Pg. 276

- NPNF2-05. Gregory of Nyssa Pg. 275

- Καὶ γὰρ καὶ ἐν τῷ Ἰορδάνῃ μετὰ τὴν τοῦ Πνευμάτος δύναμιν, καὶ πάλιν ἐν ἀκοαῖς τῶν Ἰουδαίων, καὶ ἐν τῇ μεταμορφώσει, φωνὴ γίνεται ἄνωθεν διδάσκουσα τοὺς ἀνθρώπους, καὶ σχῆμά τι μή τὸ φαινόμενον οἴεσθαι μόνον, ἀλλὰ καὶ τὸν ἀγαπητὸν Υἰὸν τοῦ Θεοῦ πιστεύειν εἴναι ἀληθῆ. Τοιαύτη φωνὴ πρὸς τήν τῶν ἀκουὀντων σύνεσιν ἐν τῷ ἀερίῳ σώματι παρὰ τοῦ Θεοῦ διετυπώθη κατὰ τὴν ἐπικρατοῦσαν τῶν φθεγγομένων συνήθειαν γενομένη. MPG.Vol. 45. Col. 993 Contra Eunomium, Lib. XII

- My translation

- An alternative translation as found in Schaff’s Nicene and Post Nicene Fathers is, “We read in the Acts that the Divine power divided itself into many languages for this purpose, that no one of alien tongue might lose his share of the benefit.”NPNF2-05. Gregory of Nyssa Pg. 276

- Ἐν ταῖς Πράξεσι μεμαθήκαμεν διὰ τοῦτο τὴν θείαν δύναμιν εἰς πολλὰς διεσχίσθαι φωνὰς, ὠς ἄν μηδεὶς τῶν ἑτερογλώσσων ἀποστεροῖτο τῆς ὠφελείας. MPG.Vol. 45. Col. 997 Contra Eunomium, Lib. XII

- My translation from Migne Patrologia Graeca. Vol. 46. Col. 695ff

- As found in the Philosophy Basics website

- See Augustine on the Tongues of Pentecost for more information

- See Basil of Seleucia on Pentecost: Notes for more information

- See Bede’s Initial Commentary on Acts 2:1-19 for more information

- Frienship in Late Antiquity: The Case of Gregory Nazianzen and Basil the Great