A history of the word gift, as in gift of tongues, throughout christian history.

How the perceptions of this word has changed over eighteen centuries and shaped our contemporary understanding.

A fourfold aim of collating, digitizing, translating, and tracing the Christian doctrine of tongues from inception until 1906.

A history of the word gift, as in gift of tongues, throughout christian history.

How the perceptions of this word has changed over eighteen centuries and shaped our contemporary understanding.

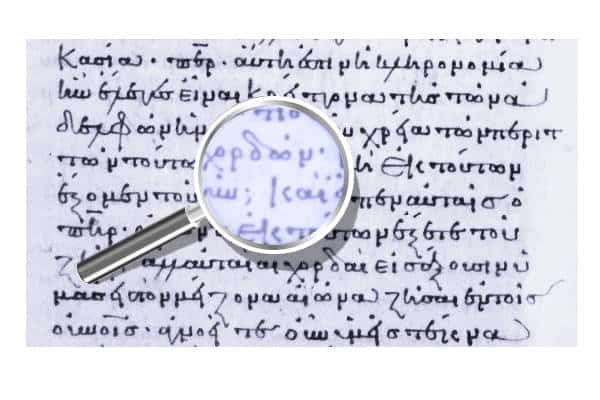

A journey that delves deeply into Greek grammar, etymology, and the politics behind the translation of Origen’s comments of I Corinthians 14:13–14.

This article covers the great third century Church Father, theologian and writer, Origen, regarding his commentary on the above passage in Greek. The coverage here is technical and produces by a step-by-step process in producing an English version. By doing so, the system reveals problems that plague the translation of ancient Christian texts.

An etymological exploration of the word χάρισμα from select writings of the Church Fathers.

Χάρισμα has a much wider semantic range than most realize and assists in a better understanding of St. Paul’s usage.

By going through a select set of writers from the third to fourth centuries, Athanasius*1, Eusebius, and Gregory of Nazianzus, a clearer picture is developing on how the ancients understood the word.

In a traditional English translation, one is forced to use gift in every instance of χάρισμα. In my translations below, I am breaking this tradition because the Church Fathers indicate a wider semantic range. Really, I am not sure if there is a one word equivalent in English for this word. The sense from these authors is that χάρισμα means this: the giving of your talents and service as an expression of thanks for what He has done in your life and reflecting God’s image in all that you do. I think endowment, expression or manifestation may be better English choices depending on the circumstance. These words do not completely match the Greek either and appear too simplistic, but comes closer in many instances.

How Pentecostals built their historical framework for their doctrine of tongues from Higher Criticism literature–a necessary but unlikely relationship.

This merging of two opposed systems, one dependent on the supernatural, and the other focused on the rational and logical with no reference to any divine entity, makes for one of the most major shifts in the history of the christian doctrine of tongues.

As shown throughout the Gift of Tongues Project, tongues as an ecstatic utterance was a new addition to the doctrine of tongues in the 19th century. There is no historical antecedent for ecstatic utterance, glossolalia and their variances before this era. Nor is there a connection with the majority of ecclesiastical writings over 1800 years which had a different trajectory.

Examining the nature, function, and history of angels in the Dead Sea Scrolls and two intertestamental books to find a connection with St. Paul’s reference of the tongues of men and angels.

Paul and the authors behind the Dead Sea Scrolls, the Testament of Job, and the Book of Enoch are products of a milieu that believed in the divine interplay between angels and the worshipper. So, if one wants to find an answer to Paul’s mysterious reference about angelic tongues, the highest probability exists in these texts.

The subject is especially important to those of the Renewalist persuasion (Pentecostals, Charismatics, and Third Wave Christians). They believe that the tongues of angels Paul refers to is to the mystical rite of speaking in tongues. The explanation is this: when a person is divinely inspired and begins speaking tongues, they are speaking in a heavenly language that angels speak.

An analysis of the Testament of Job, its controversial state on speaking in angelic tongues, and its place in the christian doctrine of tongues.

The Testament of Job’s narration of Job’s three daughters speaking in the dialect of angels piques curiosity, especially those who hold an interest in the christian doctrine of tongues. Were they speaking a supernatural language of angels that purportedly the early Christian church of Corinth produced and later the Montanists? Alternatively, were they speaking in highly exalted poetic language as the Delphic prophetesses practiced?

Why Paul never used the word synagogue to describe the movement he inspired and chose ecclesia instead—the Greek word we translate as church.

The short answer is that he couldn’t use the word synagogue for a variety of legal and administrative reasons. Ecclesia was a better fit for their role as a para-synagogue organization within the Jewish umbrella.

There is a second option but not so strong as the first one. Paul thought of ecclesia as defining his concept of Messianic Judaism a restorative movement claiming back to the time of Ezra.

The reasons and impact of Christianity’s separation from its Jewish parent.

Christianity started as a grass-roots Jewish movement that had its origins in the Galilee and Jerusalem regions.

There were two reasons that this offspring of a Jewish parent split: the destruction of Jerusalem, and their excommunication by Rabban Gamaliel II. This separation was distinct by the time of the Bar Kokhba revolt.

One must keep in mind that the separation was a gradual one. There were amicable relations between the two parties for centuries—so close that it caused competing interests.

A detailed look at praying in tongues from a historic Jewish perspective. The results may surprise many readers.

When one examines praying in tongues from a Jewish liturgical perspective, the understanding of praying in tongues changes dramatically. The most important finding is that praying in tongues was part of a list of liturgical activities noted by Paul occurring in the Corinthian assembly. A list includes speaking in tongues, hymns, psalms, and the amen construct. These are all found in ancient Jewish traditions.

They all point to the fact that the Corinthian assembly had inherited the liturgical rites of their greater global Jewish community.

A history of speaking, interpreting, and reading from 500 B.C. to 400 A.D. in Judaism and early Christianity.

An interactive infographic to help you navigate Paul’s world and how these offices later evolved in the Christian Church. Clicking on the image will bring you to the full interactive site.

IMPORTANT! Please note that the interactive file was an experiment in coding and design. The end result is that you have to wait a bit longer before the file is rendered, especially on mobile phones. My apologies in advance.

Paul’s mention of speaking in tongues in I Corinthians is deeply wrapped in the Jewish identity. The same goes for his understanding of speaking, reading, and interpreting of tongues. These rites have a rich history that goes well over 800 years. The initial origins are deeply connected to the times of Ezra.