An analysis of the Testament of Job, its controversial state on speaking in angelic tongues, and its place in the christian doctrine of tongues.

The Testament of Job’s narration of Job’s three daughters speaking in the dialect of angels piques curiosity, especially those who hold an interest in the christian doctrine of tongues. Were they speaking a supernatural language of angels that purportedly the early Christian church of Corinth produced and later the Montanists? Alternatively, were they speaking in highly exalted poetic language as the Delphic prophetesses practiced?

An obvious third question then arises. Did the tongues of angels perpetuate in the early church and beyond? No literature so far in any ecclesiastical text examined in the Gift of Tongues Project has addressed the subject. It is not a part of the ancient traditions in Western or Eastern Christianity.

These first two questions and more are the purpose of this article.

Viewpoints on the Testament of Job

The Testament of Job is a dividing line between two interpretational systems. The traditional one, which was held by Catholicism and Protestants until the 1800s, holds little value to the Testament of Job or anything understood as angelic tongues. The understanding of the christian doctrine of tongues was either miraculously speaking or hearing a foreign language during this period.

The modern definition is a different approach. The Higher Criticism glossolalic doctrine of tongues provides an answer through the Delphi prophetesses in Greek history and then winds its way to Pentecost, Corinth, and then Montanism. The concept of glossolalia in this stream of thought is “utterances approximating words and speech, usually produced during states of intense religious experience.”1 It is not considered miraculous but a psychological condition. The connection with the Testament of Job is through this framework. It does not flow through the traditional one.

Two academics from the Pentecostal viewpoint, Gordon D. Fee and especially Russell P. Spittler, modified the Higher Criticism analysis with the Testimony of Job to prove that the Christian rite of tongues as an angelic, non-human language. Consequently, it gives historical validity to the present Pentecostal doctrine of tongues.

The Higher Criticism approach ignores the wealth of literature and history of the doctrine of tongues written by ecclesiasts over the centuries. As discussed through the Gift of Tongues Project, it is a major flaw in academic research and writing over the last one hundred years—not that ecclesiastical writings are necessarily correct, but ruled out of the discussion without any consideration.2

The Pentecostal doctrine of tongues as an angelic language is on the quiet underside of the Pentecostal experience. A personal prayer language that is known only between the person and God, or a supernatural language of praise and worship, are more frequent renderings.

How this angelic tongue concept first originated in Pentecostal circles, it is not known. One must keep in mind that a casual reading of the Bible combined with a sense of mysticism could easily create such a sense in any epoch of Christianity.

What is the Testament of Job?

The plot of the Testament of Job is a 100 BC modification of the popular and old Book of Job found in the Bible.

This retelling is different and adds new twists and turns. The focus of this study about Job’s last words to his seven sons and three daughters. Job bestows his physical assets to his sons and a supernatural gift for his daughters; three heavenly made sashes that when worn, cause his daughters to enter a different mental state where eternal ones replace the present realities. It also causes them to sing exalted hymns in the dialect of certain angels.

It is hard to distinguish whether the Greek or Jewish influences dominate this book. This complexity has vexed many academics and remains a question unsolved.

This work is not in the Jewish, Protestant, or Catholic Bibles, nor is it a routine document within Christian or academic circles. The church has historically been aware of this text from inception, but its popularity for research purposes increased in the 1800s.3

An article posted on the web attributed to Michael A. Knibb and Pieter W. van der Horst, editors, Studies on the Testament of Job gives a good outline of the whole work.

Fee and Spittler on the Testament of Job and tongues

The revered Pentecostal scholar, Gordon D. Fee, promoted that the Corinthian tongues was the uttering non-human angelic language:

That the Corinthians at least, and probably Paul, thought of tongues as the language(s) of the angels seems highly likely–for two reasons: (1) There is some evidence from Jewish sources that the angels were believed to have their own heavenly language (or dialect) and that by means of the “Spirit” one could speak this dialect. Thus in the Testament of Job 48–50 Job’s three daughters are given “charismatic sashes” which when put on allowed Hemera, for example, to speak “ecstatically in the angelic dialect, sending up a hymn to God with the hymnic style of the angels. And as she spoke ecstatically, she allowed ‘The Spirit’ to be inscribed on her garment.” Such an understanding of heavenly speech may also lie behind the language of I Cor 14:2 (“speak mysteries by the Spirit”). (2) Once can make a good deal of sense of the Corinthian view of “spirituality” if they believed themselves already to have entered into some expression of angelic existence. This would explain their rejection of sexual life and sexual roles (cf. 7:1–7; 11:2–16) and would also partly explain their denial of a future bodily existence (15:12, 35). It might also lie behind their special interest in “wisdom” and “knowledge.” For them the evidence of having “arrived” at such a “spiritual” state would be their speaking the “tongues of angels.” Hence the high value placed on this gift.4

A blogger advances Fee’s teaching by the name of notsohostilepentecostal which demonstrates that there is some traction within the Renewalist community:

However, there is some historical, precedence for interpreting tongues as angelic speech, since the Jews already believed that angels had their own language and that the Spirit of God could cause someone to speak it (Fee 200-201).5

Indeed, a debate raged over this very point on a Christian chat board. One of those engaged in the discussion understood Paul’s reference to the modern rite of tongues as an angelic language:

. . .Paul was referring to angelic or heavenly languages or at least that this is what the Corinthians themselves thought, where some are not prepared to offer their own views.

For those of us who can pray in the Spirit (tongues), it is hard to imagine when the Holy Spirit prays on our behalf to the Father that he would be forced to speak a frail mortal language; do people actually believe that the Godhead and the Angelic hosts do not communicate via a heavenly tongue/communication?6

Fee cites Russell D. Spittler’s translation as found in the book, Old Testament Pseudepigrapha to build his thesis and rests solely on this reference. He does not substantiate his claims with any other source.

Spittler himself, a Harvard graduate, and now retired professor from Fuller Seminary, is also from a Pentecostal background and affiliation.7 He mixes both Higher Criticism and Pentecostal influences in his translation. This combination is not unusual nor surprising. This relationship has existed for almost a hundred years and substantiated in a previous series on Pentecostal tongues and Higher Criticism.

Unfortunately, Spittler, and then Fee who follows his line of thought, do not accurately translate Greek to make their case.

The best argument that these two can make is that that the persons allegedly speaking in the languages of angels were speaking and articulating in highly exalted hymns—ones that the brother of Job claimed to have recorded in writing and left for posterity. This type of inspiration was not unusual with Greek prophecy. Articulation of hymns and poetry was the common delivery method of visions and ecstasy for the Delphi prophetesses in ancient Greece. Their prophecies, initially induced by the volcanic fumes emitting from cracks in the chamber, could change the destiny of wars and whatever question, small or great, seekers came for.

Read the Delphi Prophetesses and Christian Tongues for more information.

It also is very simplistic to try and build a case for angelic tongues on three paragraphs of intertestamental fiction. It was never meant to be a didactic piece. One has to ignore over a thousand years of Christian and Jewish literature that relates to the tongue genre to make this case plausible.8 Indeed, the text itself, if read with serious intent, leads to a highly exalted state of praise, resulting in the production of extraordinary hymns/poems that is above regular human capacity. It has little to do with a strange or exotic language.

The above statements should suffice as a complete argument, but for the sake of thoroughness, here are the source details along with some commentary.

The Translations and the source

The Greek text is fairly straightforward. It is the English translations where one begins to see major differences and interpretations.

This article follows the numbering system displayed by the Online Critical Pseudepigrapha, and also followed by the book, Old Testament Pseudepigrapha. The headers 45 to 53 are the ones under evaluation, and 48 to 50 specifically refer to angelic tongues.

The Spittler translation

The first translation is from the Old Testament Pseudepigrapha (1983). Russel P. Spittler is the translator. I have highlighted the important passages in red.

The charismatic sashes

48:1 Thus, when the one called Hermera arose, she wrapped around her own string just as her father said. 2 And she took on another heart—no longer minded toward (Pg. 866) earthly things— 3 but she spoke ecstatically in the angelic dialect, sending up a hymn to God in accord with the hymnic style of the angels. And as she spoke ecstatically, she allowed “The Spirit” to be inscribed on her garment.

49:1 Then Kasia bound hers on and had her heart changed so that she no longer regarded worldly things. 2 And her mouth took on the dialect of the archons and she praised God for the creation of the heights. 3 So, if anyone wishes to know “The Creation of the Heavens,” he will be able to find it in “The Hymns of Kasia.”

50:1 The the other one also, named Amaltheia’s Horn, bound on her cord. And her mouth spoke ecstatically in the dialect of those on high. 2 Since her heart also was changed, keeping aloof from worldly things. For she spoke in the dialect of the cherubim, glorifying the master of virtues by exhibiting their splendor. 3 And finally whoever wishes to grasp a trace of “The Paternal Splendor” will find it written down in the “Prayers of Amaltheia’s Horn.”910

M. R. James edition (1897)

M. R. James is the first one to pen a popular English translation of Testament of Job back in the late 1800s. It is a dated read with some awkward translation solutions.

There are significant differences between his and Spittler’s translation. In the bigger picture, Spittler’s translation is the preferred choice, but when it comes to the angelic speech sequences, James’ older translation is the more literal and avoids the word ecstatically which does not exist in the Greek.

He goes by a different numbering and chapter system that is not used in the Testament of Job editions today.

23 Then rose the one whose name was Day (Yemima) and girt herself; and immediately she departed her body, as her father had said, and she put on another heart, as if she never cared for earthly things.

24 And she sang angelic hymns in the voice of angels, and she chanted forth the angelic praise of God while dancing.

25 Then the other daughter, Kassia by name, put on the girdle, and her heart was transformed, so that she no longer wished for worldly things.

26 And her mouth assumed the dialect of the heavenly rulers (Archonts) and she sang the donology of the work of the High Place and if any one wishes to know the work of the heavens he may take an insight into the hymns of Kassia.

27 Then did the other daughter by the name of Amalthea’s Horn (Keren Happukh) gird herself and her mouth spoke in the language of those on high; for her heart was transformed, being lifted above the worldly things.

28 She spoke in the dialect of the Cherubim, singing the praise of the Ruler of the cosmic powers (virtues) and extolling their (His?) glory.

29 And he who desires to follow the vestiges of the “Glory of the Father” will find them written down in the Prayers of Amalthea’s Horn.11

The Greek

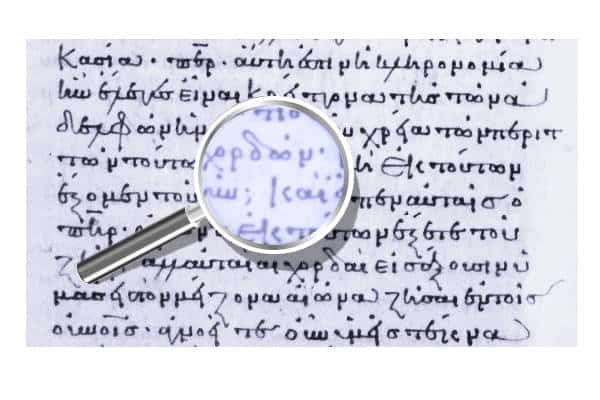

I have highlighted in red the words and phrases that match the above.

48 1 οὕτως ἀναστᾶσα * ἡ μία * * * ἡ καλουμένη * Ἡμέρα περιείληξεν τὴν ἑαυτῆς σπάρτην * καθὼς εἶπεν ὁ πατήρ * · 2 καὶ ἀνέλαβεν ἄλλην καρδίαν, * μηκέτι τὰ τῆς γῆς φρονεῖν · 3 ἀπεφθέγξατο δὲ τῇ ἀγγελικῇ διαλέκτῳ * *, ὕμνον ἀναπέμψασα τῷ θεῷ κατὰ τὴν τῶν ἀγγέλων ὑμνολογίαν · καὶ * τοὺς ὕμνους οὓς ἀπεφθέγξατο * * εἴασεν τὸ πνεῦμα ἐν στολῇ τῇ ἑαυτῆς ἐγκεχαραγμένους.

49 1 Καὶ τότε * ἡ Κασία περιεζώσατο καὶ ἔσχεν τὴν καρδίαν ἀλλοιωθεῖσαν ὡς μηκέτι ἐνθυμεῖσθαι τὰ κοσμικά · 2 καὶ τὸ μὲν στόμα αὐτῆς ἀνέλαβεν τὴν διάλεκτον τῶν ἀρχῶν, * ἐδοξολόγησεν δὲ τοῦ ὑψηλοῦ τόπου τὸ ποίημα. * 3 διότι εἴ τις βούλεται γνῶναι τὸ ποίημα τῶν οὐρανῶν , δυνησητε εὑρεῖν ἐν τοῖς ὕμνοις Κασίας.

50 1 Καὶ τότε περιεζώσατο καὶ ἡ ἄλλη ἡ καλουμένη Ἀμαλθείας κέρας· καὶ ἔσχεν τὸ στόμα ἀποφθεγγόμενον ἐν τῇ διαλέκτῳ τῶν ἐν ὕψει , 2 ἐπεὶ καὶ αὐτῆς ἡ καρδία ἠλλοιοῦτο ἀφισταμένη ἀπὸ τῶν κοσμικῶν· λελάληκεν γὰρ ἐν τῇ διαλέκτῳ * τῶν * Χερουβὶμ δοξολογοῦσα τὸν δεσπότην τῶν ἀρετῶν ἐνδειξαμένη τὴν δόξαν αὐτῶν · 3 καὶ ὁ βουλόμενος λοιπὸν * ἴχνος ἡμέρας καταλαβεῖν τῆς πατρικῆς δόξης * εὑρήσει ἀναγεγραμμένα ἐν ταῖς εὐχαῖς τῆς Ἀμαλθείας κέρας.

The actual full Greek text

The transcribed text from the original Greek minuscule is found at The Online Critical Pseudepigrapha. It is an excellent site that has manuscript variances noted as hyperlinks. The level of reading difficulty is not hard to adapt for those with New Testament Greek skills.

If you desire to delve deep into the original text, you can go to the Bibliothèque nationale de France online and view an important source minuscule text: Greek manuscript 2658 and start with folio 93 (image 100). This link gets you to the start of the important sequence beginning at header number 45. In the Testament of Job research language, this manuscript is referred to as “P”–one of the best manuscripts on Testament of Job.12

The use of ecstatically

Spittler substantiates his use of ecstatically through comparative analysis and not the Greek text. His position is found in the footnotes where the idea of an angelic language has lesser emphasis and greater towards that of a human-derived one. I have only quoted the following footnotes pertinent to this discussion. Perhaps, I am providing too much information, but since underreporting continues to remain a serious problem with the christian doctrine of tongues, this is supplied in overabundance as part of an antidote:

48a The accounts of the daughters putting on their sashes (48-50) show several common elements: (1) the name of the daughter; (2) donning the sash; (3) having the “heart changed”; (4) no longer concerned with worldly things; (5) glossolalia in the language of specified human beings; (6) a brief characterization of the contents of glossolalia; and (7) reported preservation of the speeches in mythical books (but see n. H to 48).

48d V heightens by adding “and at once she was outside her own flesh,” which parallels Paul’s ecstatic ascent; he twice wondered whether the ascent was “in the body” or “outside the body” (2Cor 12:2ff.). The changed “heart” (cf. 49:1; 50:2) refers not to conversion but appears rather to describe the onset of the ecstatic state, “the descent to the Merkabah.” When Saul was “also among the prophets,” it is said that “God gave him another heart.” Note the similarity to the language of Montanus preserved in the 4th-cent. Heresiologist Epiphanius: “Behold! Humankind is like a harp, and I a strum as a plectrum; humans sleep, I am awake. Behold! The Lord is the one who excites the hearts of humans, the one who gives them a heart” (AdvHaer 48.4.1).

48f Similarly, “the dialect of the archons” (49:2), “the dialect of those on high” (50:1), “the dialect of the cherubim (50:2), “the distinctive dialect” (52:7). The source of Paul’s “tongues. . . of angels” (I Cor 13:1)? Paul, however, does not use alone. In the account of the Pentecostal glossolalia, Luke uses the word expressly for humans (of varied nationality) and not for angels; contrast his use of “magnify” (megalunein; see n. a to 38). In ApAb 17, and angel teaches Abraham a heavenly song, recital of which leads him to a vision of the Merkabah. The singing of hymns by females (“virgins”) in the language of the cherubim—as well as the notion of the “Chariot of the Father”–is known also to Resurrection of Bartholomew (ed Budge, Coptic Apocrypha, pp. 11f., 1189)

51a Here and at 51:4, as well as 52:12 (cf. 18:2: songs of victory taught by the angel), the products of the daughter’s glossolalic speeches are described as hymns, although they are called “prayers” at 50:3. What singing angels sound like, which presumably those using their language would resemble, can be gauged from 2En 17:1 J: “In the middle of the heaven, I saw armed troops, worshiping the LORD with tympani and pipes, and unceasing voices, and pleasant [voices and pleasant and unceasing] and various songs which itis impossible to describe. And every mind would be quite astonished, so marvelous and wonderful is the singing of these angels. And I was delighted listening to them.13

The Montanists

Spittler’s introduction proceeds to make a solid connection between the Tongues of the Testament of Job and that of the Montanists in the second century AD. He thinks a portion of the Testament of Job, the piece we are looking at here, was a later emendation and insertion by the Montanists.

When the new prophecy erupted, there was no contest over canon, scripture, or doctrine. When, however, the original Montanist trio passed and the foretold end had not yet come, the movement organized and the prophetic ecstasy spread. Prophetic virgins constituted themselves into an institution. At one point—before A.D. 195—an anti-Montanist writer demanded of the Montanists where in scripture prophetic ecstasy might be claimed. In an era of canonical flexibility, a Montanist apologist, probably of Jewish background, made use of a “testament” known to him in which he found ideas compatible with his own species of Judaic practice. By creating Testament of Job 46–53, possibly inserting chapter 33, and certain other restyling, the apologist for the new prophecy produced a text wherein the daughters of Job were charismatically, or magically, lifted into prophetic ecstasy, enabling them to speak in the language of angels.14

He also alternatively speculated that these last parts of the Testament of Job may have been added by the Therapeutae–a first-century Jewish group described by Philo of Alexandria. A group who had similar structures and beliefs to those of the Qumran communities.

The Montanist argument and their association with the christian doctrine of tongues is a dubious assertion. They are but a small, speculative drop in a much larger dynamic of church history. The emphasis of Montanist influence can only occur with the de-emphasis and purposeful ignoring of major ecclesiastical texts addressing the christian doctrine of tongues.

The connection or lack thereof between Montanists and the Christian office of tongues is part of a previous series on the History of Glossolalia and specifically, A Critical Look at Tongues and Montanism

Dialects and Ecstatic speech

dialects of angels

The use of the word dialect—διάλεκτος is a key term in this whole document. One of my first concerns in studying this word is our immediate perception of it to mean regional or geographical variations of a parent language. This assumption may not be the case. This word along with apotheggomai–ἀποφθέγγομαι to utter, or sound forth, or speak one’s opinion plainly, are both parts of the Pentecostal narrative found in Acts chapter 2.

Although the sequence of words is similar between the two documents, 130 years separated their origin and written in different geographic regions. Dialect—διάλεκτος and even apotheggomai–ἀποφθέγγομαι may not share the same meaning between the Book of Acts and the Testament of Job.

After looking at διάλεκτος for some time, the emphasis is not on dialect but on language. Διάλεκτος and the Greek word for language, glossa, γλῶσσα, can overlap in meaning. Perhaps, the use of διάλεκτος is to emphasize the peculiarity or specialness of the situation.

The application of dialektos to the Testament of Job text is that the three daughters were speaking in a human language that was highly exalted and structured praise, something so well presented that it appeared to be of angelic origin. The emphasis on the word hymns in the actual Greek text is dominant in the angelic interplay.

Another clue comes from the Talmud which fosters the idea that angels were assigned to certain countries or language groups. In the case of Judaism, some advanced the idea that their angels could only comprehend Hebrew. “For R. Johanan declared: if anyone prays for his needs in Aramaic [ie. a foreign tongue] the ministering Angels do not pay attention to him because they do not understand that language.”15

If this passage is understood correctly, which some dispute the literal meaning and see a more political undertone, then Jewish thought, or some sects of Judaism, understood angels with linguistic limitations based on human language, geography, and politics.

The Dead Sea Scrolls, especially the Songs of the Sabbath, relate the divine presence of angels in worship; especially in the impartation of knowledge and highly exalted expressions. There is no emphasis or recognition of an alternative heavenly language spoken by humans in this context either.16

The description of daughters speaking in the dialect of archons or cherubim is not surprising. The Qumran communities exhibit a full hierarchy of angels and a form of worship that integrates both angels and humans. The hierarchy listed by the narrator in Testament of Job is a trope—a figure of speech emphasizing how the praise was incrementally getting stronger and more impactful.

Ecstasy

The Greek was provided to reinforce the fact that the word for ecstasy does not exist in the source text. There may be one listing that leans towards Spittler’s interpretation. The found evidence is in header 52 not included in the above text. When the angels came to take Job away, his daughters played instruments to bless the holy angels:

And they blessed and glorified, each one in the remarkable language.17

[καὶ ηὐλόγησαν * * καὶ ἐδόξασαν * * ἑκάστη ἐν τῇ ἐξαιρέτῳ διαλέκτῳ]

Spittler has some validity from this text to prove angelic tongues but the overwhelming evidence shown throughout this article weakens his assertion.

Conclusion

The writer of the Testament of Job is drawing from the ancient Book of Job and spicing it up with some Hellenistic drama with a mixture of Jewish thought. The person is integrating the ancient rites of the Greek prophetesses going into ecstasy resulting in uttering apocalyptic, prophetic, and supernatural directives spoken in hexamic poetry. The story also weaves into the narrative the growing awareness in Jewish circles the presence of angels and their heirarchy, especially in the presence of worship, enabling participants to enter into a higher state of worship, a place reserved for angels and the heavenly places. The text itself states that these daughters who spoke in the dialect of angels expressed it in hymns, and in one instance a poem, which the story narrates were written down for posterity sake.

Spittler’s translation is not faithful to the text; the word ecstatically does not exist in the Greek. He is forcing the reader to believe in his viewpoint and Fee, not looking at the actual Greek, promotes Spittler’s translation and analysis. It becomes a cornerstone of Fee’s widely influential systematic Pentecostal theology on the tongues of Corinth. It is an assertion based on one text without reference or even wrestling with the tensions and contradictions with the many and important mainline Christian texts on the subject.

There is no connection between this document and the Montanists. It is a document firmly rooted in the Hellenistic Jewish thought and practice that surrounds the first century.

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/glossolalia

- Read the article, History of Glossolalia: Patristic Citation for more information.

- Job, Testament of, as found in the Jewish Encylopedia

- Gordon D. Fee. God’s Empowering Presence. Third Printing. Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers. 1995. Pg. 200–201

- The Essential Nature of Speaking in Tongues

- A chat on Assembly of God Tongues Oct. 1, 2016. by Biblicist—Full Gospel Believer.

- A small Spittler bio. This bio is the best I can find so far. As far as I know, he is no longer actively teaching or serving at Fuller Theological Seminary.

- See the Gift of Tongues Project Page for a detailed look at the names and writings on the christian doctrine of tongues throughout the centuries

- Numbers added here in the text by me. These were not part of the original copy.

- The Testament of Job, as found in The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha. Translated by R. P. Spittler. J. H. Charlesworth, ed. Vol. 1. New York: Doubleday and Company. 1983. Pgs. 865–866

- The Testament of Job, as translated by M. R. James. Apocrypha anecdota 2. Texts and Studies 5/1. Cambridge: University Press, 1897. As found at piney.com

- http://pseudepigrapha.org/docs/intro/Testament of Job

- The Testament of Job, as found in The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha. Translated by R. P. Spittler. J. H. Charlesworth, ed. Vol. 1. New York: Doubleday and Company. 1983. Pgs. 864–867

- The Testament of Job, as found in The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha. Translated by R. P. Spittler. J. H. Charlesworth, ed. Vol. 1. New York: Doubleday and Company. 1983. Pg. 834

- The Soncino Talmud. Trans. by Epstein I. London: Soncino Press. 1935. Pg. 162

- The tongues of angels in the Qumran liturgy is an article presently in research and next to be published on my blog

- Translation is mine

Thank you heartily for this latest addition to your corpus in the Gift of Tongues Project, touching on the “tongues of angels,” and the text of the Testament of Job and its presumed connections to Delphic, Montanist, and later Pentecostal and charismatic understandings of “tongues,” particularly as discussed in the influential works by Fee and Spittler. Brick-by-brick, your are building a formidable edifice of evidence for disabusing readers of tendentious modern and contemporary distortions stemming from insufficient awareness of the historical record.

I always understood the tongues of Pentecost to be a miracle of the hearing as every man heard in their own language. Is it possible that they were speaking all the different languages at once thus being the ‘speaking in tongues’? This also was a miracle. They didn’t need an interpreter either! Thanks.

The mechanics behind the miracle, whether the speaker spoke one sentence in one language, and then another sentence in another language until all languages were exhausted is a potential theory. However, no church writers have given this consideration. Could it have been that each speaker spoke one or two languages, and the collection of speakers, miraculously speaking different one or two languages, covered the linguistic spectrum? Once again we are confronted with historical silence on the actual mechanics of this miracle. A portion of the earlier church, especially that espoused by Gregory of Nyssa, believed Pentecost was the emission of one sound and it transformed in the hearers ears. Still, that does not arrive at answering your question. I don’t have a solid answer except for theories.