A review of John Chrysostom’s works as it relates to the Christian doctrine of tongues.

His works on the doctrine of tongues are not so cut-and-dry as many portray him. A further look demonstrates far more complexity with grey areas and questions that remain unanswered.

This fourth-century Church Father is one of most quoted authors of the subject. His popularity on the topic is due to the great reverence associated with his name, the easy access of English translations, and his connection to miracles by the highly influential eighteenth-century writer Conyers Middleton. However, Chrysostom’s work is not a primary source that many have elevated it. There are much better sources elsewhere.

Table of Contents

- About Chrysostom

- Chrysostom on Montanism

- Chrysostom on the tongues of Pentecost

- Chrysostom on the tongues of Corinth

- Chrysostom on Miracles

- Clues about Chrysostom’s definition on the doctrine of tongues

- The Spirit sounding within him?

- The Corinthian tongues being a liturgical language?

- Some Additional thoughts about Chrysostom on Tongues

About Chrysostom

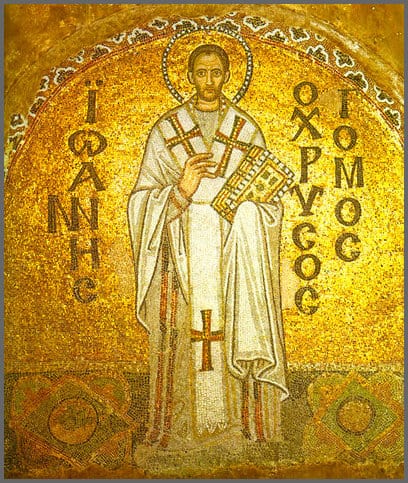

John got the title Chrysostom — which means golden mouthed, not because it was his last name, but to his great eloquence. This term was applied to him well after his death. Anyone reading one of his homilies can tell that he had the intellectual acuity combined with public acumen, and articulate speaking skills. He is one of the few that spoke or wrote in the first person within the community of ecclesiastical writers. He was considered the defacto standard for all that followed him in the Eastern Byzantine Christian world.

This is a look at his coverage of the subject with three important questions to be answered.

-

Did he believe that miracles had ceased in the Church altogether and so the idea of Christian tongues in the contemporary Church is moot?

-

What did he think happened at Pentecost? Was it the instant ability to speak in foreign languages, or was it something else?

-

What did he think of the Corinthian problem of tongues?

-

Did he recognize or argue against the Montanist practice of tongues?

Chrysostom on Montanism

The Montanist question will be answered first because it is the simplest. He did not recognize any Montanist contribution to either tongues or miracles in any of his texts.

Chrysostom on the tongues of Pentecost

Chrysostom clearly defined the doctrine of tongues as the spontaneous utterance of a foreign language unknown beforehand by the speaker. There was no concept whatsoever of a private, ecstatic or heavenly prayer language in his coverage.

Speaking in tongues was an issue that he was keenly aware of. He was constantly being asked that question, and felt it necessary to make a reply in his Homily, On the Holy Pentecost:

For if one wishes to demonstrate our faith, we believe this has been done without an assurance of a pledge or signs with it. Except those ones who have received first the sign and pledge, do not believe it concerning the unseen things. I, on the other hand, indeed show a complete faith without this. This is therefore the reason why signs are not happening now.1

His answer was that signs were for the unbeliever. The faithful require no external signs for assurance because the Christian life is an internal matter of the heart and mind. If one depends on signs as the most important factor in personally knowing God, or as the stimuli that motivates in the Christian life and witness, then signs and miracles are the guiding force in life. It becomes the central part of one’s identity which must constantly be pursued. Chrysostom favored the ascetic inward life of devotion, acceptance, and good deeds as the guiding principle in the Christian life over being directed by external signs. Miracles and signs were too abstract and impersonal as a framework for daily Christian living.

Chrysostom on the tongues of Corinth

This revered Church Father’s Homilies on Corinthians has had one of the most far reaching effects on Western Christianity. The following is an analysis of his texts, and documents the impact of them on future theologians and historians.

In almost every piece of tongues literature referencing the Church fathers, the following quote from Chrysostom is sure to be cited:

This whole place is very obscure: but the obscurity is produced by our ignorance of the facts referred to and by their cessation, being such as then used to occur but now no longer take place. And why do they not happen now? Why look now, the cause too of the obscurity has produced us again another question: namely, why did they then happen, and now do so no more?2

This is a leading statement by those of the cessationist movement who believe the supernatural era was completed at the founding of the Church. This belief concludes that the miracle of tongues did not perpetuate itself after this. Therefore, it is not necessary to trace the definition, or evolution of the doctrine of tongues because anything defined after the first century is based on a false supposition.

The fourth century leaders Chrysostom, and Augustine, along with the fifth century Cyril of Alexandria carried similar thoughts on the subject, though each one represented this concept slightly different. Augustine restricted his opinion that only the individual expression of tongues had ceased, not the corporate one. Other miracles such as healing, prophecy, etc., were still viewed as operative.3 Cyril of Alexandria held that the miraculous endowment of languages at Pentecost was a temporary sign for the Jews. Those that received this blessing continued to have this power throughout their lives, but it did not persist after their generation.4 The association between these three demonstrates that there must have been an interpretive movement of this kind in the fourth and fifth centuries that bordered on a universal thought.

However, there are problems. It does not take into account the tongues-speaking experience of the fourth century Egyptian Monastic leader, Pachomius. The writers of this account display him speaking miraculously in an unlearned foreign language, and no one in antiquity has disputed or countered the theological legitimacy.5 Basil of Seleucia who tried 50 years later to emulate Chrysostom’s style and wrote a commentary on Pentecost, did not overtly carry on this tradition of cessation,6 but then he did not disprove it either. It was simply omitted in his coverage. Neither was the doctrine found in eighth century John of Damascus texts, who liberally borrowed from Chrysostom’s works.7

These are from a small sampling, more materials may come up on these two I have not read that may contradict my opinion. Michael Psellos in the tenth century failed to recognize any of these three about cessation in his comprehensive coverage on tongues, choosing to exclusively follow Gregory Nazianzus.8

On the other hand, Thomas Aquinas in the thirteenth century sided with Augustine that the miracle of tongues had switched from an individual, to a corporate expression.9 These examples demonstrate that the cessationalist doctrine of tongues was dominant and powerful during the fourth and fifth centuries, but it was not universal. It did perpetuate, but it was not the defacto standard.

The one who captivated this doctrine for centuries was Gregory Nazianzus which had no reference to cessation at all. His technical approach can be traced in Christian literature for well over nine-hundred years.10 He did not address whether tongues ceased or perpetuated, he solely concentrated on the mechanics on how this miracle operated at Pentecost.

For more information on Gregory Nazianzus on the doctrine of tongues, see, Gregory Nazianzus on the doctrine of Tongues Intro.

The earliest that Chrysostom’s name prominently recirculated after the fourth century in connection with miracles and the doctrine of tongues was by the English Church historian, Conyers Middleton, who wrote the controversial and game-changing 1749 work, Divine Inquiry. Middleton outlined that signs and miracles have not occurred since the time of the apostles. It was written both as an antidote against the excesses of Christian mysticism during his time and the establishment of the Protestant identity separate from the Roman Catholic authority. His scant reference to Chrysostom in the above work, along with more details found in, An Essay on the Gift of Tongues,11 gained attraction to Chrysostom’s thoughts. The concept became a stolid symbol for the conservative protestant identity in 1918, when the last theological leader of a united Princeton Seminary, B.B. Warfield, published, Counterfeit Miracles.12 Warfield utilized Chrysostom as a champion of that cause. The golden mouth preacher found a prominent proponent which renewed an interest in his works within the western world. The theological idea of cessation grew prominent in many theological circles and today is known as cessationism.

Chrysostom on Miracles

Did Chrysostom really believe miracles had ceased? A further look is yes if one does not look at all the information and no if the information is examined more closely. There has been some mulling over this since the publication of Free Inquiry where Middleton himself showed some difficulties with Chrysostom on the subject.13 He cited many examples from Chrysostom about the nature of demons and their remedies; such as letters about a young friend of Chrysostom, Stagirius, who chose the monastic life, and had both physical and emotional issues which Chrysostom sought healing through exorcism.14 Another one was cures using consecrated oil,15 and also believed that the sign of the cross was a “defence against all evil, and a medicine against all sickness, and affirms it to have been miraculously impressed, in his own time, on people’s garments,”16 and lastly that forcing one possessed by a demon to be near or touching the tomb of a Christian martyr, can bring about healing.17 There is more to miracles to Chrysostom than what was supplied by Middleton. In Homily 38 of the Acts of the Apostles, Chrysostom described a boy who was miraculously healed.18 Many of these stories revolve around demons which were considered a normative experience in Greek everyday life. It was not an unusual or extraordinary event. This was so prevalent that it would not be labelled as a special gift that only happened at the birthing of the Church. Added to this fact that Chrysostom believed the central Christian identity was “to enlist in Christ’s army for warfare against the devil and his hosts”.19

Secondly the healing of the young boy was either a direct intervention by God, or by the laws of nature. It was not attributed to the powers of a faith healer, which Chrysostom believed whose office had died. The healing via consecrated oil, and the sign of the cross suggests that Chrysostom believed that miracles had transferred from the individual and into the corporate Church expressed in the form of rituals. This is a similar concept espoused by Augustine who believed that the gift of tongues did not die, but rather its expression switched from the individual to the Church.20

The downgrading of miracles is consistent with Greek philosophic principles, in which even St. Paul recognized as different from Jewish perceptions, “For indeed Jews ask for signs and Greeks search for wisdom.”21 Signs were not a priority, understanding and applying meaning was utmost. This was very evident even at the time of Origen whose coverage of I Corinthians dwelled greatly on the concept of knowledge rather than the literalness of the text.22

Chrysostom demonstrates a cautionary approach to miracles. His response reflects a man who lived a very ascetic and restrictive lifestyle. The goal of every Christian’s life was not the outward activity such as healings or miracles, but the purity and selflessness of the inner soul. He very much minimized individualism and espoused corporate good. This can be gleaned from his writing found in his Homilies in Matthew 9:32;

For, as to miracles, they oftentimes, while they profited another, have injured him who had the power, by lifting him up to pride and vainglory, or haply in some other way: but in our works there is no place for any such suspicion, but they profit both such as follow them, and many others.23

He also outlined here the real danger of pride within those who perform miracles and cautioned against this type of leadership. Conversely, he demonstrated an openness to miracles happening through an anointed person. He believed many succumb to the temptation of pride. Perhaps he is following in the same line of thinking as Origen that the decline in miracles was due to the lack of altruistic, pious, and holy individuals in his generation.24 Chrysostom never named anyone in his lifetime ever achieving this status. This was likely why he venerated deceased saints who had achieved a high spiritual status in their lives that very few could ever achieve. He believed that they had miraculous powers even after they died and those attending by their graves could muster restorative power. This veneration in some Churches still exist today. The alleged skull remains of Chrysostom’s body, was brought out for a brief public viewing in 2007 at the Monastery of Mt. Athos. It was claimed to be healing people who appeared by it.25

Rowan A. Green took a deep look at Chrysostom and miracles in his book, The Fear of Freedom: A Study of Miracles in the Roman Imperial Church, and felt pressed to ask the question, what is Chrysostom worrying about? He answered by writing, Chrysostom identifies the quest for miracles with the magical practices he naturally supposes Christians must avoid. Still more, the Jews tend to become scapegoats in Chrysostom’s polemic.26

Another dynamic may be the idea of political stability. The central authority of the Church was based on literature, liturgy, ritual and offices, which were uniformly observed and established. If signs and wonders became the central focal point, it would have severely challenged the structure of the Church and could bypass established leadership, and all other established principles.

Clues about Chrysostom’s definition on the doctrine of tongues

Chrysostom had further important points in his Homilies on I Corinthians which is imperative to look into:

I Corinthians 14:3. . . .And it was thought great because the Apostles received it first, and with so great display; it was not however therefore to be esteemed above all the others. Wherefore then did the Apostles receive it before the rest? Because they were to go abroad every where. And as in the time of building the tower the one tongue was divided into many; so then the many tongues frequently met in one man, and the same person used to discourse both in the Persian, and the Roman, and the Indian, and many other tongues, the Spirit sounding within him: and the gift was called the gift of tongues because he could all at once speak various languages. . .

I Corinthians 14:10 There are, it may be, so many kinds of voices in the world, and no kind is without signification:” i.e., so many tongues, so many voices of Scythians, Thracians, Romans, Persians, Moors, Indians, Egyptians, innumerable other nations. . .27

It is consistenly found in Chrysostom’s hermeneutic that the tongues of Babel, Pentecost and Corinth were the same thing. He mixes verses from many books to make a linear narrative on the doctrine.

His conclusion that tongues-speech in I Corinthians was obscure, his virulent anti-semitism, and narrow literalist interpretations all contributed to difficulty understanding this subject. He could not comprehend a Jewish antecedent as a background to Paul’s narrative of I Corinthians.

The Spirit sounding within him?

The above passages demonstrate that the miracle of Pentecost was the supernatural endowment of speaking in different languages. One portion of the text requires some additional thought. What did he mean by “the Spirit sounding within him.”? The actual Greek reads: τοῦ Πνεύματος ἐνηχοῦντος αὐτῷ which should properly be translated as:

While the Spirit teaches to him

This is slightly different from the standard English translation quoted above. It changes the nuance and should then read: “and the same person used to discourse both in the Persian, and the Roman, and the Indian, and many other tongues, while the Spirit teaches to him: and the gift was called the gift of tongues because he could all at once speak various languages.”

The old English version leaned on the Latin translation of the text which emphasized the idea of the Spirit sounding within (insonantes Spiritu) rather than the Greek which, according to Donnegan’s Greek Dictionary, believed Chrysostom used the word in other works to mean to teach or instruct.28 Secondly the Latin put the text into the ablative rather than keep the sense of the Greek genitive absolute.

The reader may think that this is an innocuous point being made. There are a number of ways to understand the tongues miracle. The first one was that the person thought in their own language and as they began to speak, their thoughts were divinely intercepted and their lips produced sounds in different foreign languages, which the Latin translation could be understood leaning towards. It was an external miracle. Therefore there was little intellectual involvement on behalf of the speaker. Or it can be that the speaker spoke a single language, and the hearers heard in their own language. Another argument was that the miracle happened internally. The person miraculously understood and comprehended a language not previously known, had immediate fluency, along with full voluntary control of what he was saying, which the Greek tends to promote. The text illustrates that Chrysostom believed it was an internal miracle. He did not explain whether this was a temporary phenomenon with those at Pentecost, or that it persisted with them throughout their lives.

The Corinthian tongues being a liturgical language?

Chrysostom further wrote an analysis of I Corinthians 14:15 that dwelled on the subject of tongues as a special foreign language used in the Church service:

I Corinthians 14:15 See how this one gradually building the argument demonstrating that such a thing is not only unprofitable for everyone else, but for himself, if it is so, his mind is unfruitful?

If someone should utter on in the Persian language, or in some foreign one, and additionally he does not know what he is saying, therefore it will also henceforth be alien to him, not just to another person, because the mastery of the voice would not be understood. In fact, there were formerly many having the gift of prayer by aid of a language. The language was being uttered — a prayer language being emitted whether in the Persian or Roman voice, and meanwhile, the mind did not know the thing being spoken.29

The text infers here that Chrysostom was aware the earlier Church had a religious liturgical language issued in the form of prayer, and it was supposed to be used universally throughout Christendom — however, he wasn’t sure what that liturgical language was. His guess was either of the two more prominent languages within his realm; Latin or Persian. He did acknowledge that there were once people skilled in this practice within the Church liturgy, but not within his time. This is an odd statement because Cyril of Alexandria, whose influence in Alexandria, Egypt, was only forty years later, stated that a Christian liturgical language, along with an interpreter-like-person called the keimenos was still in use within the Churches of Egypt.30

Chrysostom also pointed out that those previously who read or spoke in the religious liturgical language did not necessarily know what they were reading or saying. They were trained to simply read out the sounds, or speak them out from memory. It shows that this practice had been abandoned in the Antioch area by his time but not necessarily throughout the universal Christian community.

Some Additional thoughts about Chrysostom on Tongues

His fourth homily on the Acts of the Apostles clearly spells out that Pentecost was the supernatural endowment of one or many foreign languages.31

He also provides more material from his homilies On the Holy Pentecost about the passages in the Book of Acts where people being baptized, miraculously spoke in foreign languages:

The person in the process of being baptized immediately was uttering in the sound of the Indians, Egyptians, Persians, Scythians, and Thracians — one man was taking on many languages. 32

He takes a position here that the person was spontaneously speaking in all the languages of the world. It is a broad statement which does not explain the mechanics behind this. Was the person speaking a few words in one language, then switching to a second, and so on, until complete? Wouldn’t that take far too long? And would it be considered a miracle only to say a few words in each language and then switch to another?

These questions are unfortunately not answered. Chrysostom himself realized this in his address on the doctrine of tongues in his homilies On the Holy Pentecost. He bluntly dived right in, stating that believers do not need signs. External things are insignificant. He knew his audience would not completely buy into this and added, “But I see that to be a teaching extending out for a long time. On which account I am going to bring an end to the word while adding a few thoughts.”33 He never completely finished the topic. It would have been helpful for posterity that he did. So he left us with a lot of question marks as to what he meant.

This may be the reason why Nazianzus’ writing of the subject perpetuated for centuries and his opinions did not. ■

- See A Snippet from Chrysostom’s “The Holy Pentecost” Homilies on the Pentecost 1:4(b) to 5. My translation

- Homily 29 on First Corinthians. Translated by Talbot W. Chambers. From Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, First Series, Vol. 12. Edited by Philip Schaff. (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1889.) Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight. http://www.newadvent.org/fathers/220129.htm.

- see Augustine on the Tongues of Pentecost Intro

- see Cyril of Alexandria on Tongues: Conclusion

- see Pachomius on Speaking in Tongues

- see Basil of Seleucia on Pentecost

- see John of Damascus on Tongues: Notes

- see Michael Psellos on the doctrine of Tongues

- see Thomas Aquinas on the Miracle of Tongues

- I previously wrote one thousand years but the last important instance of his debate is noted in Aquinas’ works. So it is round about 900 years

- Conyers Middleton’s Essay on the Gift of Tongues

- http://www.monergism.com/thethreshold/sdg/warfield/warfield_counterfeit.html#one

- Conyers Middleton. A Free Inquiry – New Edition. London. J. and W. Boone. 1844. Pg. 103

- The original text is found in Ad Stagirium a daemone vexatum. MPG. Vol. 47. Col. 423-448

- Homilies on Matthew. 32

- IBID Divine Inquiry Pg. 103

- In Julianum Martyrem. MPG. Vol. 50. Col. 669

- Acts of the Apostles. Homily XXXVIII, as found at New Advent. Translated by J. Walker, J. Sheppard and H. Browne, and revised by George B. Stevens. From Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, First Series, Vol. 11. Edited by Philip Schaff. (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1889.) Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight.

- Rowan A. Greer. The Fear of Freedom: A Study of Miracles in the Roman Imperial Church. Penn State Press. 2008. Pg. 54

- See Augustine on the Tongues of Pentecost for more info.

- I Corinthians 1:22 NASB

- See Origen on Knowledge

- Homily on Matthew 9:32

- see Origen on the Gift of Tongues for more info.

- http://www.johnsanidopoulos.com/2010/01/contemporary-miracles-of-st-john.html

- The Fear of Freedom: A Study of Miracles in the Roman Imperial Church. Penn State Press. 2008. Pg. 56

- Homily 35 on First Corinthians. Translated by Talbot W. Chambers. From Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, First Series, Vol. 12. Edited by Philip Schaff. (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1889.) Revised and edited for New Advent by Kevin Knight.

- Donnegan Pg. 494 [677]

- translation is mine

- See Cyril of Alexandria on Tongues: Conclusions for more info.

- Saint Chrysostom. Homilies on the Acts of the Apostles and The Epistle to the Romans. Vol. XI. as found in A Select Library of the Nicene and Post Nicence Fathers of the Christian Church. Philip Schaff, ed. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. 1899. Pg. 25ff

- See A Snippet from Chrysostom’s “The Holy Pentecost”

- My translation. Homily on the Holy Pentecost 1:4(b) to 5

Using Scripture as a source, in I Corth 13:10 the Apostle Paul states “when the perfect comes”….it appears in context that this will be Christ Jesus in His second coming or when believers in Christ will meet Him….the context is verse 12 which says ” For now we see through a glass darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known.”…..It appears Paul is looking to see Christ Jesus face to face, and not the completed Scriptures as some say is the context for the “perfect comes”. “Face” in the normative context is something related to a living object, and not what would be the completed Scriptures as having a “face”. I’d think God the Holy Spirit might have used another word, if meaning the completed Scriptures. I’m not trying to win an argument or position, but humbly trying to understanding the Cessation view…Blessings