The relationship between Pentecostals and the historians Philip Schaff, F. W. Farrar and others along with their influence on the modern definition.

How the traditional definition of tongues all but died and was replaced by the Pentecostal practice of Pentecostal glossolalia — an umbrella term for the language of adoration, singing and writing in tongues, and/or a private act of devotion between a person and God.

Before 1906 there were only two definitions of speaking in tongues within the traditional Christian practice:

- Tongues as the spontaneous ability to speak a foreign language not previously learned or known beforehand

- tongues as someone speaking in one voice and everyone hearing in their own language.

In the 1800’s, this definition expanded:

- Firstly, redefined as glossolalia: an ecstatic state that produces speech-like syllables. A social phenomenon, not a miraculous one

- then modern Pentecostal tongues: a spiritualization of the glossolalia doctrine.

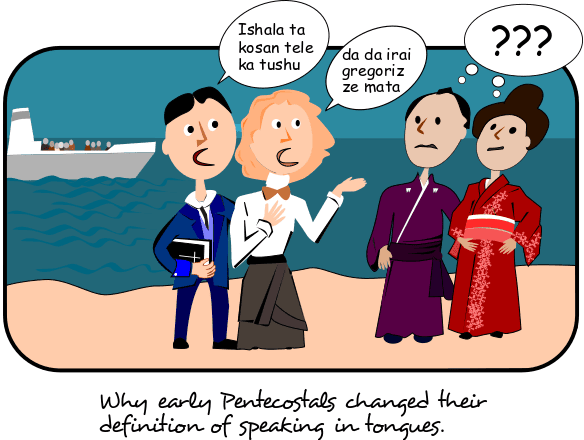

The Azusa Street revival began as a traditional Christian tongues doctrine: many people imbued with the Holy Spirit were perceived with the ability to speak a foreign language spontaneously. The Azusa people and those involved in the greater grassroots holiness movement saw this as a sign to evangelize all the nations. This theology was called Missionary Tongues.

As previously noted in Pentecostal Tongues in Crisis, Pentecostal missionaries arrived at their foreign destinations and discovered they did not have this supernatural linguistic ability.