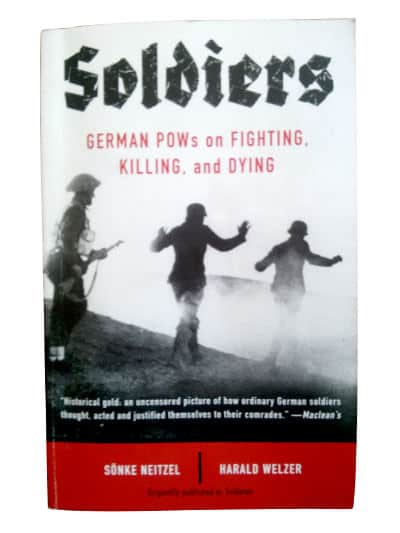

Soldiers: German POWs on Fighting, Killing, and Dying, by Sönke Neitzel and Harald Welzer is an eye-opening book about the amorality and monstrosities of German soldiers in the Second World War and how this mindset developed.

Sönke Neitzel, a German historian and “currently Professor of Military History at the University of Potsdam”1 and Harold Welzer, a German social psychologist, combine to build a definitive and unassuming portrait based on taped conversations of Germans detained in Allied war prisons. These were secretly done and transcribed by British and American intelligence agents during the Second World War. These dialogues helped the Allied forces better understand the technological and strategic initiatives within the German military during the War. However, the social and moral dynamics found in these discussions had little strategic value and were left unused for over five decades.

Neitzel accidentally found out about these records while working as a visiting lecturer in Glasgow in 2001. Further investigation uncovered a large library of over 100,000 pages. Neitzel contacted Harold Welzer who was electrified about the findings: “. . .men were talking live, in real time, about the war and their attitudes towards it. It was a discovery that would give unique, new insight into the mentality of the Wehrmacht and perhaps of the military in general.”2 Indeed, the documents revealed a rich wealth of information to build a historical and psychological portrait. The findings offered lessons not only on the German war machine, but war in general.

Their analysis dispelled the myth that German soldiers were merely following orders or that the violence was committed by a few rogue groups or leaders. The dialogues portrayed the everyday soldier, airman, or seaman, along with the upper echelons of military brass were compliant in the atrocities. Even the civilian administration was guilty. The mass executions were a lure for a good show, a “semipublic spectacle with a high amusement value.” The circumstances extended even to police officers who wanted to kill someone for the thrill of the experience.3

The book does not delve into the hearts and minds of soldiers and leaders who worked inside the concentration camps, only those captured in battle.

The authors sought to discover what influenced German soldiers to shift into an amoral and monstrous mindset. They concluded the most important factors were unlimited power, unbridled youth, shame, group dynamics, and the military frame of reference. The analysis ruled out any socio-economic status, religious identity, education level, or ethnicity as a contributing factor. Nor was ideology a force. Most soldiers were apolitical.4 The infamous SS or its armed wing, Waffen units, were neither entirely responsible. Soldiers in the general armed forces, the Wehrmacht, had also perpetrated severe violations. The actions were consistent of any participant in the German enterprise.

Wartime soldiers are by and large youngish men who have been separated from their real or would-be partners and freed from many social constraints. When stationed in occupied areas, they are given the sort of an individual power they would never enjoy in civilian society.” 5

Soldiers were most concerned with their own individual survival, their next home leave, the loot they could pilfer, and the fun they could have, and not the suffering of others, especially those considered racially inferior. Soldiers’ own fate was always at the center of their perception. Only in rare cases did the fate of enemy troops or occupied peoples seem worthy of note. Everything that threatened one’s own survival, spoiled the fun, or created problems could become the target of unlimited violence.6

The book is a much harsher reality than the one portrayed in the movie, Schindler’s List, but less intense than the narrative provided by Philippe Aziz, in his book, Doctors of Death, — which focused on the German medical leadership and experimentation on Jewish subjects. The atrocities being widespread and not restricted to loose canons or hierarchical force was also substantiated by Edwin Black in his book, IBM and the Holocaust: The Strategic Alliance Between Nazi Germany and America’s Most Powerful Corporation where he shows that low-level clerks and commoners who did the data entry for identifying Jewish identity in Nazi-occupied territories were also direct contributors to the holocaust.

The prison conversations bring to light the general war problem of autotelic violence — “violence committed for its own sake without any larger purpose.”7 This is a natural outcome when the modern rules of law are suspended in times of war. The authors shared a conversation of a Luftwaffe observer named Lieutenant Pohl, who said it only took him three days to get used to the violence. After the fourth day, he enjoyed shooting down soldiers — it was breakfast amusement. On one occasion he wanted to drop bombs on a crowded Polish town because he was so full of rage and he didn’t give a damn. “It would have been great fun if it had come off.”8

Another conversation shows how autotelic violence had become routine:

“We sank a children’s transport. . . which gave us great pleasure.”9

Neitzel and Welzer make a formative statement that the rape, tortures, mass killings, forced plunder, genocides, and other war-related fatalities were nothing new in the historical annals of war. The difference was the increased dimension and expression of such phenomena exercised by the Germans. The introduction of new technology and weaponry – the switch from horses, cannons and bayonets to planes, tanks, semi-automatic rifles, and weapons of mass destruction, allowed for death and destruction beyond any historical framework. This greatly expanded the ability to destroy without any limit.10 The coverage of later wars and revolts by the revered journalist, Robert Fisk, clearly points out that these evils are not a proprietary problem of Germany, but an expression of humanity’s dark side wherever a social system collapses and there are no limits on violence.11 Another distinction within the German establishment was the elimination of certain groups that had “nothing to do with the war itself.”12

The authors build a framework to answer why out of 17 million members of the Wehrmacht, there were only 100 attempts at rescuing Jews.13 They believe the solution can be found in their frame of reference. The frame of reference was built around military values in a wartime situation. It became extreme because German society was passive, tolerant of repression, restricted their opinions to the private realm, and did not question the military value systems.14 More importantly was the individual soldier’s relationship with his immediate comrades. Going against the group existential existence, even if the purposes are inhuman, is tantamount to the individual’s emotional or physical death.15

Naturally, the horrendous acts of violence against Jews are included in many conversations. These come as no surprise, but the callousness and the uncaring does. Soldiers got extra rations, pay incentives and other perks for execution duty.16 But a switch began to happen as the war began to shift into Allied control. More emphasis was placed on hiding the killings, including exhuming bodies and destroying any evidence. There was a certain fear that if the Germans lost the war, Jews would look for revenge.

The prisoners conversations about sexual assaults, rapes and violence against women was shocking. The soldiers’ dialogues carried the sense of pleasure and power without any remorse. While some women did receive better treatment, it was far from altruistic — the soldiers traded protection for a sexual favours. The women were eventually shot and killed in order to hide the abuses and avoid public shame of sex with a Jewish woman. There was also rampant prostitution. The authors described that the sexual predation was widespread throughout the military and led to a major spread of gonorrhoea and syphilis that overwhelmed the medical facilities. Antibiotics treatment had not been introduced yet, and contracting a VD severely weakened the military’s available manpower. The military responded by setting up and sponsoring brothels in order to counter this.

But without doubt, sex was part of soldiers’ everyday existence – with a whole series of consequences for the women involved.17

A statistic for the amount of rapes, violence, and murders against women done by German soldiers has never been given. However, the conversations by the soldiers indicate the rate must have been significantly high.

The overall discussions were so dark, contorted and distasteful, that my mind has difficulty imagining them. But they compelled me to ask, what kind of persons are we dealing with here? How could men with such strong values of hard work, respect, and honour, turn dark so quickly and heartlessly? How could they go home and speak to their wives, mothers or sisters about what they did? Once the war was over, was there a place for them to live? Or did their conscience already die and they moved about as empty shells?

The authors answered the first two questions. The latter questions about the post-war lives of these soldiers are left unanswered. How could these people find peace? Corrie Ten Boom, a Dutch woman dispatched to a concentration camp by the Nazis for concealing Jews in her family home, and author of Hiding Place gave one clue. While giving a speech in Germany shortly after the War, a former prison guard at Ravensbruck concentration camp approached her, though not familiar with each other, asked her for forgiveness against the cruelty he enacted on the people at Ravensbruck. She felt both were liberated through the act of forgiveness: letting go of her bitterness that could cripple one’s body and soul, and him, from the prison of his guilty conscience.18 Was this type of remorse and wanting catharsis widespread with post-war soldiers, or was Ten Boom’s encounter an exception? Soldiers: German POWs on Fighting, Killing, and Dying, would have been a more powerful book if the authors followed up interviewing a few of these prisoners that did such atrocities to find whether they remained defiant or later became remorseful.

The popular term today in military mental health circles for soldiers in this circumstance is called moral injury — the “reaction stemming from perpetrating, failing to prevent, or bearing witness to acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs.”19 Most literature on moral injury tend to treat the person as a victim and a mental health problem. I think the authors of Soldiers: German POWs on Fighting, Killing, and Dying would dispute the claim of the perpetrator as a victim. Although many situations can be a perceived sense of guilt and not real, the victims of a person committing a moral injury are either dead, disabled or emotional invalids, while the perpetrator goes on living. This is a cop-out that avoids addressing the moral failure and prevents the perpetrator to admit wrongfulness and receive full catharsis.

The stories shared in the book evoke such anger for real justice. If there is no remorse given by the perpetrators, or any attempt to say sorry to those who have been wronged, the only solace is that these people will have to answer before God at the day of reckoning for the blood of the innocents.

What can be learned from this book for today? This is not a book about ideology but the everyday person in the German military. The idea that, I don’t give a rat’s ass about anything except what affects me, was consistent within all the discussions and a key undertone among many others. A condition that allows hatred to ignite and go unchecked. A mindset that allows the person to complete instructions even against one’s moral convictions, and removes the person from any social responsibility. This circumstance opens a pandora’s box of monstrous proportions when no rules exist. Apathy is a much harder vice to correct than hatred and is the essence of inhumanity. This is not a simply a problem of World War II Germany – examples can be found in almost any major modern conflict in the world. Every society has to guard against this sin.

Would I recommend this book? This is one of the most difficult readings I have ever done. It is well written, researched and documented, but the subject matter is grisly. This book is not recommended for the casual reader, or for anyone personally haunted by the bitterness of war, but a source work for the historian, social psychologist, teacher, or journalist. Neither should one attempt to read in one, two or three sittings. The very nature forces one to read only bits at a time and put it away for a while.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/S%C3%B6nke_Neitzel

- Pg. Ix

- Pg. 137

- Pg. 319

- Pg. 165

- Pg. 77

- Pg. 49

- Pg. 46

- Pg. 69

- Pg. 321

- See the The Great War for Civilisation for more info

- Pg. 76

- Pg. 100

- Pgs. 34–35

- Pg. 336

- Pg. 126Ff

- Pg. 169

- https://www.guideposts.org/inspiration/stories-of-hope/guideposts-classics-corrie-ten-boom-on-forgiveness?nopaging=1

- Psynopsis: Canada’s Psychology Magazine

Christians should not be involved in the military. It is unbiblical to give oath allegiance to a human person telling you that it is okay to kill in the name of your country. Orders in the military often conflict with Christian morals and doctrine. Can you serve in medical or other service? At times that might seem to be okay. The America army present day is not different spread around the world raping murdering and torchering people in the name of protecting the homeland.