How glossolalia entered the christian doctrine of tongues vernacular and became the entrenched form of interpretation.

The 1800s was the era of a significant transition in the interpretation and understanding of the doctrine of tongues. This epoch was the time when the traditional interpretation which consisted of a supernatural spontaneous utterance of a foreign language gave way to enigmatic themes such as ecstatic utterances, prophetic utterance, ecstasy, and glossolalia.

Table of Contents

- Why speaking in tongues became a popular item for scholars to publish in the 1800s

- Ecstasy vs. Glossolalia

- The people behind the new definition

- The propagation of the new definition

- August Neander and his influence on Philip Schaff in promoting tongues as an ecstatic utterance

- The expansion of the new definition into the world of English literature

- Conclusion

Why speaking in tongues became a popular item for scholars to publish in the 1800s

A significant factor that fostered intense study was the Irvingite movement’s claim in the 1830s to have revived the gift of tongues. Their emphasis and practice of this doctrine brought the study of the gift of tongues out of a long slumber and into the critical attention of religious scholars throughout Europe.

The assertion about the Irvingites may be an over-generalization because the story of the alteration begins a few short years before them, but without this controversial apocalyptic and tongues-speaking group, international inquiry to the doctrine of tongues would never have occurred. There would have been no catalyst for propagating a new definition.

Ecstasy vs. glossolalia

One has to be mindful of the use of the word ecstasy used throughout this article. Medieval Catholic mysticism had defined ecstasy as a prerequisite state before a divine encounter – very similar but not exactly to what Renewalists today call baptism in the Holy Spirit. Indeed, this was a such an essential word in the late medieval vocabulary that the massive sixteenth-century Greek dictionary by Stephanus, Thesaurus of the Greek Language, allowed considerable space to define this Greek word. Ecstasy was an established religious concept that academics easily understood. The German academic community had taken this familiar religious symbol to express this phenomenon. However, the idea of ecstasy was not sufficient in the long run. It was the starting point in the evolution of the doctrine of glossolalia.

The people behind the new definition

The rise of glossolalia can be traced to Germany in the late 1700s and the 1800s. This era is the apex where the Rennaissance, Reformation, Humanism, Protestant, and anti-Catholic fervor all combined to produce some of the most significant historical and philosophical works from a christian framework.

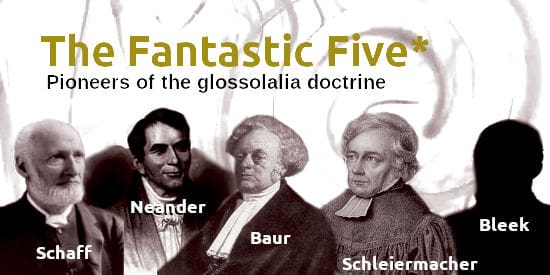

The story of glossolalia begins with five German scholars who promoted a fresh new approach to Biblical interpretation that purposely tried to avoid the trappings of traditional and enforced interpretations of Biblical texts:

Friedrich Schleiermacher whose method of interpreting the Bible along with his systematic theology, has granted him one of the most potent and influential personages that only the likes of Augustine can topple. He did not like institutional dogma or forced creeds and approached theological subjects from a sociological perspective. He promoted that any process cannot be forced to conform to an established framework and a conclusion does not have to arrive at a preconceived end.

A fellow teacher of Schleiermacher at the University of Berlin, W.M.L. de Wette, an Old Testament specialist who refined the idea of myth as a valid form of exegesis.1

- Ferdinand Christian Baur the founder, leader and teacher at Tübingen School of Theology2 who was deeply influenced by Schleiermacher and later by the philosophical influences of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. Hegel is a major figure in his own right, but his direct influence on glossolalia is faint. However, he created a new framework for Biblical interpretation which allowed such ideas to spawn.

Friedrich Bleek, a student of de Wette and highly praised by Schleiermacher himself, became one of the foremost German Biblical scholars of all time. He rose to prominence when he published “Origin and Composition of the Sibylline Oracles,” and “Authorship and Design of the Book of Daniel.”3

Last, but perhaps the most influential on the modern definition of speaking in tongues, was August Neander. August Neander was a disciple of Schleiermacher but more conservative in his views and less speculative on theological subjects.4 He also taught at the University of Berlin along with Schleiermacher and de Wette.

Schleiermacher does not have a direct say in the development of glossolalia to the christian doctrine of tongues, but his framework to allow such inclusion is obvious.

The propagation of the new definition

The late 1800s historian, author and Biblical exegete, Heinrich Meyer believed the first known academics to publish a critical work on tongues defined as an ecstatic utterance were Friedrich Bleek and FC Baur around 1830, just before the Irvingite movement’s break-out.5 He wrote:

Bleek believes that glôssai is a poetic, inspired mode of speech, whereas Baur believes it to be “a speaking in a strange, unusual phrases which deviate from the prevailing use of language.” – partly borrowed from foreign languages.6

The Exegetical Handbook authored by Heinrich Meyer believed that most commentators followed the standard definition that speaking in tongues was either a spontaneous speaking in a foreign language or the ability to easily learn a new language through study before Bleek and Baur came out with their alternative opinion.7

A German dissertation on tongues in 1836 entitled, Die Geistesgaben der ersten Christen: insbesondre die sogenannte Gage der Sprachen, by a man named David Schulz concluded that the most significant thinkers on the subject were Bleek, Baur, and Augustus Neander.8 Neander came a little later than the first two, but his contribution had more of a universal impact.

These three are critical early works. Almost all modern scholarly and clinical Biblical interpretation trends on the gift of tongues trace to them.

Two nineteenth-century Anglican scholars, Chr. Wordsworth and Rev. Edward Hayes Plumptre would disagree. Plumptre believed the glossolalia doctrine to be the “theories of Bleek, Herder, and Bunsen,”9 and Wordsworth attributes Heinrich Meyer, de Wette, and Bunsen.10 However, the texts they allude to cannot be located, and this study is unfortunately restricted to English translations of German texts. Based on English texts found so far, Heinrich Meyer’s evaluation and other works combine to mark Bleek, Baur, and Neander as the top three.

August Neander and his influence on Philip Schaff in promoting tongues as an ecstatic utterance

Neander was the more prolific expositor and his literature was highly praised. He was referred to by more theologians on the doctrine of tongues than any other. It was through him the modern definition became an entrenched one throughout western Christendom.

His legacy in religious studies was so great that Philip Schaff, who edited the highly praised and popular publication, History of the Christian Church, conceded that his work was an updated and modernized version of Neander’s writing.11 Schaff was trained in Germany, but moved to the US as a professor and widely disseminated Neander’s views. Neander also influenced Frederick Farrar, an English theologian, and writer, who convincingly brought Neander’s thoughts to the favorable attention of English readers.

The basis of Neander’s opinions can be credited to two writers, one named Herder, which is not detailed any further in Neander’s writing. The author is likely Johann Gottfried Herder. The second was FC Bauer, whom he greatly praised.

particularly Bauer, in his valuable essay on the subject in the Tubinger Zeitschrift für Theologie, 1830, part ii., to which I am indebted for some modifications of my own view.12

Neander believed the first-century experience was a spiritual language; an abstract mystical experience not related to the gifting of a foreign language:

“Thus the speaking in foreign languages would be only something accidental, and not the essential of the new language of the Spirit. This new language of the Spirit is that which Christ promised to his disciples as one of the essential marks of the operation of the Holy Spirit on their hearts.”13

He penned that the second-century Church had altered the definition. Instead of the initially intended language of the Spirit, the second-century Church redescribed the event as speaking in foreign languages.14

According to Neander, three aspects of the tongues doctrine gained prominence and became the traditional stance in the third century. Pentecost was a miraculous outpouring, enabling unlearnt men to speak in languages they did not know at the time of the apostles. This event would not reoccur shortly after their death, and from that time, the universal promulgation of the Gospel was completed through extensive language study.

“Accordingly, since the third century it has been generally admitted, that a supernatural gift of tongues was imparted on this occasion, by which the more rapid promulgation of the Gospel among the heathen was facilitated and promoted. It has been urged that as in the apostolic age, many things were effected immediately by the predominating creative agency of God’s Spirit, which, in later times, have been effected through human means appropriated and sanctified by it; so, in this instance, immediate inspiration stood in the place of those natural lingual acquirements, which in later times have served for the propagation of the Gospel.”15

This revered theologian also knew that his definition clashed with the traditional one and readily admitted a sharp departure, “If, then, we examine more closely the description of what transpired on the day of Pentecost, we shall find several things which favour a different interpretation from the ancient one.”16

For those who argued that the miracle of foreign languages was necessary for the early establishment of the faith, he built a refutation. He felt that the use of xenoglossolalia was unnecessary for the expansion of Christianity because Greek and Latin already were ubiquitous as a first or second language for those nations and peoples connected to the Roman empire.

“But, indeed, the utility of such a gift of tongues for the spread of divine truth in the apostolic times, will appear not so great, if we consider that the gospel had its first and chief sphere of action among the nations belonging to the Roman Empire, where the knowledge of the Greek and Latin languages sufficed for this purpose…”17

He concluded that the tongues indicated in I Corinthians to be ecstatic:

“something altogether different from such a supernatural gift of tongues is spoken of. Evidently, the apostle is there treating of such discourse as would not be generally intelligible, proceeding from an ecstatic state of mind which rose to an elevation far above the language of ordinary communication.”18

Neander pondered about the Irvingite experience. He concluded that although the Irvingites believed they were spontaneously speaking in a foreign language unknown to them, the reality demonstrated otherwise. “Still less can I admit the comparison with the manifestations among the followers of Mr. Irving in London, since as far as my knowledge extends, I can see nothing in these manifestations but the workings of an enthusiastic spirit, which sought to copy the apostolic gift of tongues according to the common interpretation, and therefore assumed the reality of that gift.”19

Schaff felt that Neander had failed in his examination of tongues and charged him with being a victim of rationalism.20 — though it is hard to find the difference in his position with Neander’s. Schaff believed the gift of tongues to be, “an involuntary, spiritual utterance in an ecstatic state of the most elevated devotion, in which the man is not, indeed, properly transported out of himself, but rather sinks into the inmost depths of his own soul, and thus, into direct contact with the divine essence within him . . .”21

He simply reinforced Neander’s position. One of the significant proofs he used was by the analogy of the Irvingites;

“The speaking with tongues in the Irvingite congregations, as it manifested itself in the earlier years of this sect in England, was at first a speaking in strange sounds resembling Hebrew, after which the speakers continued in their English vernacular…”22

He then reported of an eyewitness account of a Michael Hohl, who described an Irvingite experience. He saw a person going into a trance, produce violent convulsions and then, “An impetuous gush of strange, energetic tones, which sounded to my ears most like those of the Hebrew language.” 23 Schaff then used the Irvingite experience to conclude:

“Could we appeal to the Irvingite glossolaly, as a reasonable analogy, we should here have a similar elevations, in which according to Hohl’s account above quoted, the ecstatic discourses were delivered first in strange sounds, like Hebrew, and afterwards, where the excitement had somewhat abated, in the English vernacular. Yet this analogy might be used more naturally to illustrate the relation between speaking with tongues and interpretation of tongues.”24

He also hesitatingly used the Irvingites, with some caveats, as a point in the evolving tongues history:

“The speaking with tongues, however, was not confined to the day of Pentecost. Together with the other extraordinary spiritual gifts which distinguished this age above the succeeding periods of more quiet and natural development, this gift, also, thought to be sure in a modified form, perpetuated itself in the apostolic church. We find traces of it still in the second and third centuries, and, (if we credit the legends of the Roman church), even later than this, though very seldom. Analogies to this speaking with tongues may be found also in the ecstatic prayers and prophecies of the Montanists in the second century, and the kindred Irvingites in the nineteenth; yet it is hard to tell, whether these are the work of the Holy Ghost, or Satanic imitations, or what is most probable, the result of an unusual excitement of mere nature, under the influence of religion, a more or less morbid enthusiasm, and ecstasis of feeling.”25

Philip Schaff was very intrigued by the gift of tongues, and it must have been an important religious topic within the religious realm during his time. In the first-ever meeting of the Society of Biblical Literature in the US held in January 1880, Schaff chose to publicly read his work, “The Pentecostal and the Corinthian Glossolalia.”26

Schaff’s view on speaking in tongues was limited to an academic audience. It wasn’t until the next author, Frederick Farrar, published a book that met a much broader audience in the English speaking world and the doctrine took the next step to becoming a universal standard.

The expansion of the new definition into the world of English literature

This new definition was restricted to Germany, but this significantly changed in the English world when Frederick Farrar published in 1879; The Life and Work of St. Paul.

This author and his works may be forgotten in the annals of history, but in his time, he was well-known. Not only did this Englishman tirelessly work his way through the ranks to be the Dean of Canterbury27, but a friend to Charles Darwin and later a pallbearer at Darwin’s funeral.

Farrar promoted that the tongues of Pentecost had nothing to do with a foreign language. “Pentecost, does not contain the remotest hint of foreign languages. Hence the fancy that this was the immediate result of Pentecost is unknown to the first two centuries, and only sprang up when the true tradition obscured.”28

Once again, the influence of Neander is clearly stated. “I do not see how any thoughtful student who really considered the whole subject can avoid the conclusion of Neander, that “any foreign languages which were spoken on this occasion were only something accidental, and not the essential element of the language of the Spirit.”29

He introduced a newly-made noun into the English language, glossolalia, with this statement:

“The glossolalia, or “speaking with a tongue,” is connected with “prophesying”–that is, exalted preaching–and magnifying God.”30

The Oxford Online English Dictionary previously attributed Farrar and an author named Lily as the creators, but both have been removed from the present dictionary with no reference to any antecedents at all.31 The Websters Revised Unabridged Dictionary 1913, traced the introduction of the word glossolalia from only Farrar.32

Nothing substantial has been found yet on the author named Lily, though Oxford Dictionaries associate him with Farrar, his views must have been closely aligned.

Conclusion

The formulation of glossolalia was developing. However, questions still linger. Do the primary sourcebooks agree that the introduction of the glossolalia concept occurred around 1879? Were there strong objections to the new definition? These questions and more are answered in this series.

Next: A History of Glossolalia: did it exist before 1879?

- Protestant Theology and the Making of the Modern German University. Pg. 194

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ferdinand_Christian_Baur

- http://www.1902encyclopedia.com/B/BLE/friedrich-bleek.html

- 1902 Encyclopedia Britannica

- Meyer, Heinrich August Wilhelm. Critical and Exegetical Handbook to the Epistles to the Corinthians. Edinburgh: T & T Clark. Translated by D.D. Bannerman. W.P. Dickson, editor. 1887. Pg. 366.

- Meyer, Heinrich August Wilhelm. Critical and Exegetical Handbook to the Epistles to the Corinthians. Edinburgh: T & T Clark. Translated by D.D. Bannerman. W.P. Dickson, editor. 1887. Pg. 371.

- Meyer, Heinrich August Wilhelm. Critical and Exegetical Handbook to the Epistles to the Corinthians. Edinburgh: T & T Clark. Translated by D.D. Bannerman. W.P. Dickson, editor. 1887. Pg. 365

- David Schulz. Die Geistesgaben der ersten Christen: insbesondre die sogenannte Gage der Sprachen. Breslau: A. Gosohorsky. 1836. Pg. 3

- “Tongues, Gift of” by E.H. Plumptre. Dictionary of the Bible. William Smith, LL.D. ed. London: John Murray. 1863. Pg. 1556

- Wordsworth, Chr. The Greek New Testament. Vol. 2. London: Rivertons. 1930. Pg. 44

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philip_Schaff

- Augustus Neander. Planting and Training of the Christian Church by the Apostles. London: Henry G. Bohn. 1851. 3rd ed. Vol. 1, Pg. 15. The spelling of Bauer rather than Baur may be a transliteration problem, but it was FC Baur.

- IBID. Neander. Pg. 14

- “This continued to be the general use of the term for the first two centuries, until, the historical connexion with the youthful age of the church being broken, the notion of a supernatural gift of tongues was formed.” IBID. Neander. Pg. 16

- IBID. Neander. Pg. 9

- IBID. Neander. Pg. 12

- IBID. Neander. Pg. 10

- IBID. Neander. Pg. 11

- IBID. Neander. Pg. 12 A previous version stated that Neander personally visited the Irvingite congregation while Irving was still leading. It cannot be substantiated that he either went to London for this purpose or at the time of Irving’s life.

- Philip Schaff. History of the Apostolic Church with a General Introduction to Church History. Trans. By Edward D. Yeomans. New York: Charles Scribner. 1859. Pg. 201

- Philip Schaff. History of the Apostolic Church with a General Introduction to Church History. Trans. By Edward D. Yeomans. New York: Charles Scribner. 1859. Pg. 199

- Philip Schaff. History of the Apostolic Church with a General Introduction to Church History. Trans. By Edward D. Yeomans. New York: Charles Scribner. 1859. Pg. 198

- Philip Schaff. History of the Apostolic Church with a General Introduction to Church History. Trans. By Edward D. Yeomans. New York: Charles Scribner. 1859. Pg. 198

- Philip Schaff. History of the Apostolic Church with a General Introduction to Church History. Trans. By Edward D. Yeomans. New York: Charles Scribner. 1859. Pg. 202

- IBID. Schaff. Pg. 197

- http://www.sbl-site.org/SSchapter1.aspx

- http://www.victorianweb.org/authors/farrar/bio.html

- Frederick W. Farrar. The Life and Work of St. Paul. London: Cassell and Company. 1897 (originally published in 1879). Pg. 53ff

- IBID. Farrar. Pg. 53ff

- IBID. Farrar. Pg. 53

- http://dictionary.oed.com. I can’t say when they removed this but am absolutely sure it existed. This dictionary is how I originally found Farrar’s name.

- Websters Revised Unabridged Dictionary 1913. Found on the web Bootlegbooks

Tongues, at first was used as an evangelical tool only! A gift of God was given to followers of Christ. The Dead Sea Scrolls seem to indicate the may have used ecstatic utterances. Note they died out. The Catholic Church reports ecstatic utterances starting up again during the Dark ages. Note the defeats suffered by the church campaigns by the Islomics. The Great Awakening challenged many church beliefs and practices and even the existence of God. Thanks Germans and Europe. NOT! God will not tolerate such abuse of a gift but for so long. I would have to think The second coming will be speeded along with the ungodly use of tongues as seen in the churches of today. Today as a true evangelical tool of human communication it would be a miracle more than a gift as in the earliest churches. Human psyco babble or of Satin, the gibberish of today is wrong. Come Lord Jesus!

Not so. It just needs interpreting.

While a student at the Hebrew University I was taught by a Jewish professor that the earliest understanding of the word prophesy in Hebrew was ecstatic utterance and is translated that way in the newest English translation of the Tanach by the Jewish Publication Society. These incidents are the prophesying of the 70 elders, the occasion of Saul prophesying and the prophets themselves in the book of Samuel. This would substantiate that there is nothing new under the sun and although rare the speaking in strange utterances under the influence of the Holy Spirit has always been present among God’s people.

I believe the Biblical reference you are referring to is I Samuel 10 verses 10 and 13 which reads in the original 1917 version of the Jewish Publication Society’s Tanakh as; “And when they came thither to the hill, behold, a band of prophets met him; and the spirit of God came mightily upon him, and he prophesied among them. . . And when he had made an end of prophesying, he came to the high place.”[1]

The 1985 version of the JPS Tanakh has since changed the verse to follow what you described, “And when they came there, to the Hill, he saw a band of prophets coming toward him. Thereupon the spirit of God gripped him, and he spoke in ecstasy among them. . . And when he stopped speaking in ecstasy, he entered the shrine.”[2]

The original Hebrew reads:

וַיָּבֹאוּ שָׁם הַגִּבְעָתָה, וְהִנֵּה חֶבֶל-נְבִאִים לִקְרָאתוֹ; וַתִּצְלַח עָלָיו רוּחַ אֱלֹהִים, וַיִּתְנַבֵּא בְּתוֹכָם

וַיְכַל, מֵהִתְנַבּוֹת, וַיָּבֹא, הַבָּמָה

Note especially the verb וַיִּתְנַבֵּא which is used for prophesied or as in the case of the JPS 1985 version, spoke in ecstasy. This verb is from הִתְנַבֵּא . This is typically used for prophesying or foretelling. I can’t think of an instance where the semantic range includes ecstasy. Not even the modern online Hebrew dictionary, Melingo, has ecstasy for this word in its list of English equivalents.[3] The Septuagint has προφητῶν[4] and the Latin Vulgate renders as prophetavit.[5] Both do not relate to the function of ecstasy, but the prophetic office.

The 1985 JPS edition follows the pattern as the 1970ish New English Bible did in its translation of Acts 19:16 where the translators rendered the passage of Paul causing people to speak in tongues of ecstasy and prophesy.[6] These are not typical of English translation practice and are deviations from the standard. The 1985 JPS edition is different from the 1917 version because it is adding a modern interpretation of prophecy. The editors decided to add the Greek classical prophetic rite in describing prophecy rather than the traditional Jewish/Christian one. This is consistent with modern interpretation, but this line of thought cannot be found earlier than the 19th century.

[1] http://www.mechon-mamre.org/p/pt/pt08a10.htm

[2] http://nocr.net/bexpo/english/engtnk/index.php/1Sa/10

[3] http://www.morfix.co.il/

[4] http://www.ellopos.net/elpenor/greek-texts/septuagint/chapter.asp?book=9&page=10

[5] http://www.latinvulgate.com/lv/verse.aspx?t=0&b=9&c=10

[6] https://charlesasullivan.com/1904/the-history-of-tongues-as-an-ecstatic-utterance-examining-the-source-books/

My apologies for the Hebrew not being formatted correctly but the comment section of WordPress does not properly support this.

Good answer, bro. These revisionists have no shame.

Thank you for your work. I came across this site while seeking to understand how and why glossolalia became acceptable. I am neither an ancient language nerd or a specialist in religion but I have been on both sides of the tongue debate and find myself wanting to look at each side more thoroughly. While you seem to think that glossolalia is the universal standard for tongues, I assure you it is not. While it may have gained much traction in the last twenty years, the debate is still ongoing and I know of many biblical theologians and apologists that still believe the gift of tongues is the supernatural ability to speak foreign languages. Therefore the debate is between glossolalia and xenoglossia.

You have a point but I think the discussion you are referring to is the historic debate, not the contemporary one. The contemporary expression has its antecedent in xenoglossia, then adapted to a modified form of glossolalia in the early 1900s. There is little or no representation of xenoglossia in the contemporary accounts.

Help me understand what you mean that there is no representation of xenoglossia in the contemporary accounts. Are you saying xenoglossia was represented in history but in the early 1900’s, it was debunked and today almost no one says it’s xenoglossia? Even if that’s true, does that in and of itself make glossolalia right? Because in reading this article and “A History of Glossolalia: did it exist before 1879” of which I have only read about one-third, that seems to be what you are saying. What I am saying is there are still Christians out there who hold to the historical view and discount the contemporary view and how they arrived at it. I don’t think the accounts you wrote about prove glossolalia, and maybe it’s not your intention to prove it. Maybe you aren’t defending glossolalia at all and are simply writing about its origins. In which case, I apologize for jumping to conclusions. I am leaning towards xenoglossia in Acts and glossolalia in I Corinthians. In Corinthians, Paul in rebuking them for misusing the gift of tongues. Therefore leading me to ask if xenoglossia is the true gift of tongues and glossolalia was other unholy tongues that even today are being used in pagan religions and Pentecostalism as well as Evangelicalism. Though it’s clear Paul is rebuking the Corinthians, what’s unclear is if they were misusing the true gift, xenoglossia, or speaking in unholy tongues (glossolalia). I’m not sure Scripture gives a difinitive answer.

The purpose of the article is a beginning portrait of the doctrine of glossolalia. It is not my intention to prove it, but document its addition to the Christian doctrine of tongues. The Church has traditionally understood Pentecost as the miraculous ability to speak a foreign language or the audience hearing a foreign language until the doctrine of glossolalia became the dominant perception after 1879. The ancient Church writings hardly address Paul’s address in a substantive way, and usually lump Pentecost with Corinth. However, there are two important exceptions on Paul’s address that lead one to believe that it had no connection with Pentecost whatsoever. It was a liturgical problem based on the rites of the ancient synagogue. More information can be found on this topic at https://charlesasullivan.com/4683/the-language-of-instruction-in-the-corinthian-church/

Greetings checkout our website at https://manassaschurchofgod.org/

Resources/Bible Study Podcasts/Bible Tongues Explained.

I think you will find the study interesting as we as informative and biblically based.

Thanks,

Bob

Thanks for sharing, for other readers who may difficulty navigating the links to find their stance on tongues, here is the link, https://manassaschurchofgod.org/doctrines/speaking-in-tongues/

You claim that it was Farrar who introduced the term glossolalia into the English language – are you aware of John William Donaldson’s “Christian Orthodoxy Reconciled with the Conclusions of Modern Biblical Learning, A Theological Essay, with Critical and Controversial Supplements”?

It contains a small chapter on glossolalia.

https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=yF_obaKksKcC&hl=de&pg=GBS.PR23

No, I was unaware. Thank you for showing this important piece of information. It will be integrated into the article in a week or less.