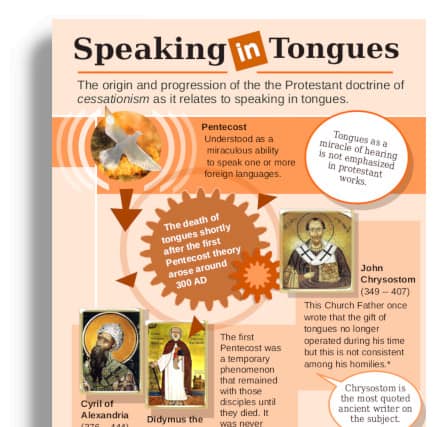

Introduction to a four-part series on cessationism, the de-emphasis of miracles, and especially how it relates to speaking in tongues.

Table of Contents

- Part 1

- Introduction

- Reasons for the rise of Cessationism

- Part 2

- The Excess of Miracles in the Medieval world and the need for correction

- The earlier De-Emphatics: John Chrysostom, Augustine Bishop of Hippo, Cyril of Alexandria*, and Thomas Aquinas

- Part 3

- The Early Protestant De-Emphatics: Martin Luther and Jean Calvin

- The Church of England and Miracles.

- The Puritan Influence: William Whitaker, William Perkins, James Ussher, the Westminster Confession, and later Confessions

- The Latitudinarians

- The Rationalists and Deists

- Part 4

Cessationism from the 1800s and onwards: the Baptists, Presbyterians, B. B. Warfield, Christian higher education, John MacArthur, and more.

Introduction

Cessationism is a religious term used in various protestant circles that believe miracles in the church died out long ago and have been replaced by the authority of Scripture. Cessationist policy is typically found in Presbyterian, conservative Baptist, Dutch Reformed churches, and other groups that strictly adhere to early Protestant reformation teachings.

It is a doctrine that had its zenith in the late 1600s, waned a bit in the 1800s and recharged in the 1900s. Today, the doctrine of cessationism has considerably subsided. However, it cannot be ignored if one is doing a thorough study of the doctrine of tongues. It is an important part of history.

According to cessationists, defining or explaining the contemporary Renewalist (Pentecostals, Charismatics and Third Wavers) practice of speaking in tongues or any other miracle outlined in Scripture is an outdated question. They don’t happen today. Therefore it is not necessary to do an in-depth historical or theological analysis about the nature and purpose of miracles in the present world.

The results are part of the Gift of Tongues Project whose fourfold aim is to identify, collate, translate (where necessary) and trace the doctrine of tongues from inception until the early 1900s. The doctrine of cessationism was not planned to be a part of the Project. However, later research has demonstrated it has an important story to tell in relation to the doctrine of tongues requiring inclusion.

The subject of cessationism deeply touches on the nature and definition of miracles—one of the most complex questions in the Christian faith.

Theologians have attempted to harmonize the mystery of miracles with common sense and science for centuries but the definitive answer still remains elusive. Although no movement or person has ever conclusively resolved this tension, the quest to find an answer is an interesting adventure.

Cessationism is not a black and white subject and takes a few surprising twists and turns. For example de-emphasis is a more suitable term at the birthing of the movement because the earliest Protestant leaders still believed in miracles, albeit in a restricted sense. Cessationism refers to a later strand that outrightly denies the possibility of any faith initiated miracle in the present age.

Reasons for the Rise of Cessationism

Cessationism began as one of the earliest Protestant doctrines in the 1500s. It can be understood from a variety of perspectives.

First of all, it was a theological counter against the excess of miracles and veneration of saints. The Protestant backlash was to outrightly denounce these features. An alternative framework was formulated for Christian living which emphasized exclusive obedience to the precepts and truths found in the Bible without any reference or emphasis on miracles. They concluded nothing supersedes, parallels, or equals Scripture. The doctrine generally subscribed to the idea that miracles tended to appear less and less as the New Testament period closed. The logical conclusion was that miracles ceased at this time.

This created a new problem. Such an emphasis on Scripture alone can lead to Bibliolatry—that is the worship and adoration of the Bible itself. It becomes a legal text that one is obligated to follow regardless of the reason, conscience or consent. It cannot be questioned and the guardians of the ancient texts can become tyrants in the application of the principles. Words and semantics then become the forefront of Scripture rule and lead into an abstract world of interpretation that only a few higher authorities can understand and apply. The reader will discover a small taste of this as they progress through these articles.

Secondly, the doctrine developed as a counter-argument. The Catholic Church argued that the Protestant Movement was illegitimate because it lacked confirmation through miracles. The Protestants volleyed back that the Catholic world had legitimized unorthodox activities through the manipulation of supposed miracles to the point of changing the Christian identity, doctrines, and overriding Scripture. The rejection of Catholic miracles became a rallying point in the Protestant identity and became one of their base principles.

Thirdly, cessationism developed in an era of England’s fear and hatred of Catholicism. England in the late 1600s was politically rife with anti-Catholicism—any semblance of Catholic association was certain to be discarded. There were constant fears of a ‘Popish plot’ to undermine English society and almost any negative political event could be ascribed to this.1 English theology incorporated this fear in their writings and was reflected in the development of cessationism.

The rejection of Catholic miracles at the earliest Protestant inception did not completely eradicate the concept of miracles. The Reformists still believed in a limited view of miracles, especially ones that could not be traced to the Catholic rites. However, within a century after the Reformation, the de-emphasis began to expand past the anti-Catholicism and develop its own distinct structure. The doctrine became an eclectic mixture of ideas collected from the rationalist movement and concepts unique to English theology.

Catholic literature demonstrably showed that the manifold expressions of miracles perpetuated throughout their history. The Protestant counter argument was this—the majority of miracles expressed by Catholics over these 1800 years were exaggerated imaginary expressions that can be reduced to myths and legends. When one reads many of the miraculous accounts in historic Catholic literature, the explanations go beyond suspending the regular laws of nature and venture into the world of incredulous that lacks any common sense. This argument of imaginative miracles has some logical truth to it that cannot be quickly dismissed. On the other hand, one cannot throw out every supposed Catholic miracle. Each miracle requires evaluation on its own merit. While the majority is easy to toss away for faulty logic, a small group may pass. A serious look may show some precious truth at the initial event but the story became greatly exaggerated later on that obscures the original fact. Regardless, these disputed miracles remain perceptions that must be respected at minimum for their didactic and historical value.

For more information on the perpetuation of tongues in the Catholic Church, read A Catholic History of Tongues: 30 to 1748 AD

The Protestant community was divided on the topic of miracles. Cessationism was not actively promoted within the large Methodist or the burgeoning Holiness movements that were popular in the late 1800s.

The cessationist movement does have some high profile early church supporters and the reasons why early Protestants supported this claim make good sense. A few important early church writers found that the visual display of miracles can easily lead to exhibitionism, pride, and personal gain. The art of miracles had little value in developing a moral christian character which many like Origen, Chrysostom, and Augustine prized.

The de-emphasis of miracles according to Protestant tradition was initially led by Chrysostom and Augustine. However, these early protestant writers fail to clarify that this concept was never universally accepted and laid dormant for almost 1100 years.

Cessationism was never a grass-roots movement, nor did it ever become a central doctrine that represented the wide swath of Protestant sects throughout Europe or in England. It is a doctrine never embraced by the Catholic Church. It became part of a doctrinal system promoted by the Puritan thinkers in the 1600s and has been articulated in different forms ever since.

The next three articles are an expanded story of de-emphasism/cessationism. Particular emphasis is placed on the Church of England, its splinter groups, and the evolution of this doctrine in the Americas. The doctrine of tongues will be touched on lightly.

Click here for Part two of the series Cessationism, Miracles, and Tongues: Part 2.