The religious expressions of prophecy and especially speaking in tongues by the Camisards in 18th century France.

The Camisards have a special narrative in the annals of Christian history and it is a sad one. Their story would have been forgotten if their speaking in tongues and their habitual use of prophecy was their mark in history. However, these are mere expressions of a greater problem of political and religious persecutions that continually harassed and cost so many lives. It is estimated that 500,000 Camisards fled France or were killed.1 These pogroms are the more important story, but the persecutions opened new Protestant expressions of piety that were unique, especially the realms of speaking in tongues and prophecy.

A deep look at Maximilien Mission’s book, Le Théatre Sacré des Cévennes ou Recit de Diverses Merveilles, published in 1707, gives some vitals answers to the Camisard religious experience. This is the sole primary source for this article. He took eyewitness accounts of the Camisards from this period and organized them according to each person’s testimony. Le Théatre Sacré des Cévennes is a seminal work into the minds and workings of the Camisard movement.

This book piques those who are curious about the history behind the Christian doctrine of tongues.

His work clearly defines the Camisards speaking in tongues as a foreign language, especially the spontaneous waxing eloquence in French. There was no reference to a non-human or angelic language. Nor was there any association with the idea of glossolalia within the Camisard experience.

This miracle in the French language gave the Camisards a perceived divine approval. The empowering was their sign of judgement on the French King and the Catholic Church. The sign was specifically directed to the French universe and did not extend to other Protestant controlled countries such as England.

One must understand that the Camisards did not speak French as their native tongue. They spoke a language called Occitan that, at least in the 1700s, had a closer affinity to Spanish. The majority of Camisards were illiterate and uneducated.

The above statements cannot be left unqualified. The rest of this article will explore this statement along with the role of prophecy within the Camisard movement.

The Camisards were part of the Huguenot movement in the late 1600s and early 1700s in the rugged mountains of south-central France called Cévennes. The Huguenots were France’s version of the Protestant faith that had spread to various communities throughout Europe and the Americas.

They were a sub-culture of the greater Huguenot community. Because of the persecutions and the absence of any defined leadership, their forms of worship evolved into distinct expressions.

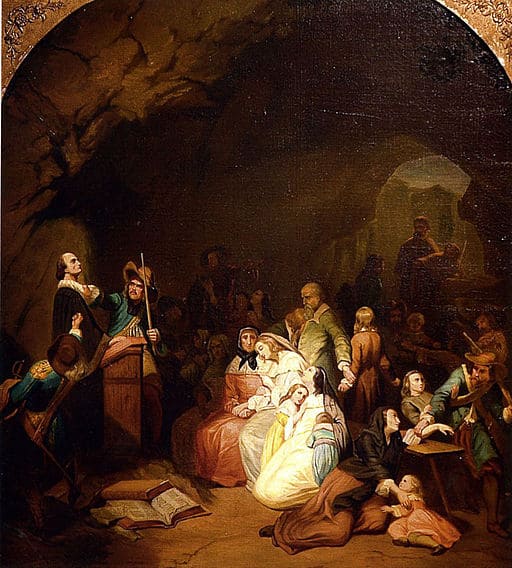

For political and religious reasons, the Catholic-influenced French Government called on the military to eradicate the Huguenots and its subsidiary Camisard movement within their borders. Soldiers were billeted to Huguenot homes and their mission was to dragonnade the Huguenots to Roman Catholicism. This dragonnade represented a special rank of the French military who were arguably scripted from the basest and worst elements of the army. They began an unbridled policy of brutality and suppression. In the eyes of the French soldiers, Huguenots had no legal rights to property, possessions, security or any protection under the law. These conditions were ripe for pecuniary gain and personal abuse by the soldiers. The Huguenots were ultimately given ultimatums; lose all property and personal rights, face imprisonment, death, rape, children removed and given to Catholic families, torture or exile. These conditions could all be revoked if they converted to Catholicism. Those who were leaders or teachers of the Protestant faith suffered an even worse judgement. They were immediately killed or forced to flee.

The testimonies contained in Maximilien Mission’s book showed a strong distaste to Catholic based authority. They believed the Pope was the Antichrist and the Catholic Church was the new whore of Babylon. These perceived signs, along with the severe persecutions, were signals heralding an end-of-world scenario.

The Camisards were poor and geographically isolated. The Huguenots in other regions of France were generally better-off and had easier access to neighbouring, non-hostile countries. These circumstances slowly forged the once pacifist Camisards into a reactionary force. The war between themselves and the better equipped French military can better be described as an insurrection. A war that the Camisards could never realistically win.

Prophecy strengthened the community resolve against the relentless pressure from King Louis XIV and his forces from 1685 to 1705. Prophecy was the vehicle by which they expressed their anxiety, tension, rhetoric and communal vision.

Catharine Randall definitively narrates the role of prophecy and tongues in the Camisard life. Her book, “From a Far Country: Camisards and Huguenots in the Atlantic World,” synthesizes the complex pieces of the Camisard faith and describes these two offices in detail:

Often, several prophets arose within the same family. Camisards gathered in great numbers to hear the prophecies; greatly consoled and inspired, some in the audience themselves experienced the “gifts.” In the absence of the clergy, the Camisards viewed these new, experiential manifestations as para-ecclesial ways to continue their conversations with Christ. The prophecies embodied the most literal understanding of the Protestant rejection of the Catholic doctrine of intercession and mediation, and of Calvinist reliance on scripture: these humble folk spoke directly with God through their prophesying, experiencing him face to face. In Relation sommaire des merveilles que Dieu fait en France (1694), Claude Brousson describes this belief in immediacy of access to the divinity: “Deprived of the word of God, of evangelism, of a regular worship service, of orderly sermons, of an emotionally appealing but also rational form of religiosity, the Camisards turned towards a belief in ‘inspiration.’”

As these prophecies evolved from consolation and instruction to calls for militancy, the Camisard began to select as leaders exclusively men who experienced this gift of tongues and prophecy. If such manifestations ceased, the leader was promptly replaced by another inspiré.2

The Camisards believed that when a person went into a spiritual empowered state, it was usually demonstrated in these conditions:

- grand agitations throughout the whole body, and particularly the chest3

- speaking while sobbing – a sign of humility and repentance 4

- falling to the floor5

- prophesying or speaking divine things that is signified with the following introductory words, “Je te dis, mon enfant. . .”

One or more of these types of manifestations must take place in order for it to be a confirmed prophecy.

The Camisards then called this state l’inspiration and often employed the synonym, l’ecstaxy. The formal use of the article demonstrates a special religious significance. There may be a distinction between the two words, but the author did not supply enough material to make an informed declaration on the difference between the two. L’Ecstaxy could easily be interpreted by the modern French reader to mean excitement. However, this noun has a specific religious usage that is rooted into the Latin language and Roman Catholic mystical practices. The word was originally found in the Latin and made its way untouched into English. Unfortunately ecstasy presently has strong sexual connotations outside of religious usage in contemporary American society but there is no alternative solution. Ecstasy denotes a special divine religious experience in this context.

The Camisard testimonials are very quick to identify that the miracles of emboldened or miraculous speech happened to both male and females, infants, mothers, youth, and adults. This strengthened their perceived argument that the Camisards were a movement directly controlled by God.

In reference to miraculous tongues-speech, it is hard to tell whether they were especially relating to the gift of tongues or emphasizing boldness of speech. This boldness empowered anyone at any time who normally did not have the persuasive speech to speak against the established authority.

The Bible, specifically Matthew 10:17-19, contains references to a specially anointed boldness that God will endow people when they are put on trial, persecuted, or imprisoned for faith reasons. This persecution validated the Camisard experience, and conversely vilified the French Government and the Catholic Church.

This divine emboldening allowed illiterate people to articulate clearly and persuasively. Infants also had the power to persuasively preach the power of repentance in a foreign language unknown to them beforehand which they thought to be the divine sign of speaking in tongues. Infants speaking in tongues is a distinctive practice of the Camisards and cannot be traced to any other earlier influences, nor did it propagate after them. For example, this is the testimony of a Jean Vernet, given in 1707:

About a year before my departure, two of my friends (Antoine Coste and Louis Talon) and myself, went to visit our mutual friend Pierre Jaquet at Moulin de l’Eve near Vernou. As we were together, a girl of the house came calling her mother who was with us, and said to her, “Mother, come see the child.” After which the mother herself called us, saying to us that we should come see the little child who was speaking. She added that it was not meant to frighten us and that this miracle had already occurred before. We all immediately ran towards the child.

The infant, aged 13-14 months, was swaddled in the cradle, and had never yet spoken by himself or walked. When I entered with my friends, the child was speaking distinctly in French, of a fairly high voice given his age; in such a way that it was easy to hear him through the whole room. He exhorted (like the others I had seen in the inspiration) to works of repentance, but I was not paying close enough attention to what he was saying to recall any of the circumstances. There were at least twenty people in the room where this infant was, and we were all weeping and praying around the cradle After the ecstasy ceased, I saw the child in his ordinary state. His mother said to us that he had some agitations of the body at the beginning of the inspiration, but I did not notice this when I came. It was a difficult thing to acknowledge because he was wrapped-up in his swaddling clothes! I also heard of another small child at the breast who spoke too at Clieu, in Dauphine.6

Jacques Dubois, de Montpellier’s eyewitness account added to this concept of children miraculously speaking eloquent French. He related a remarkable story of a child speaking in French but also prophesying, “qu’une partie de la grande Babylone serait détruite l’an mil sept cent huit.” — “that a portion of Babylon the Great will be destroyed in 1708”.7 This testimony shows the blending of prophecy, tongues and apocryphal vision into one seamless theme.

He also stated that he had seen more than 60 children between the ages of three to twelve speak and prophesy under inspiration.8

The gift also was also found among the adult community. Jean Vernet explained about his mother and sisters who spoke in tongues and prophesied:

I left Montpellier around May 1702. The first people I saw in inspiration were my mother, my brother, my two sisters and a cousin Germaine. It has now been thirteen years at least since my mother received her gifts; she always had them since that time until my departure, and I learned from the various people who had seen her not long ago, she is still in the same state. She has been detained in prison for eleven years now.

My sisters received the gift some time after my mother had received it; one at the age of nineteen, the other eleven. They died in my absence. My mother’s greatest agitations were of the chest, which made her produce great tears. She spoke nothing but French during the inspiration; which gave me a great surprise the first time I heard her; because she had never tried to say a word in this language, nor has ever done since, at least to my recollection;. . .9

It is not understood why the Camisards emphasized women and children prophesying and speaking in tongues. From my understanding of the Irvingites later on in 19th century England, women speaking in public or taking any form of leadership was severely frowned upon. This may not extend to French Camisard life. However, one can make a consensus that the features of women and children in the forefront of the Camisard religion are a peculiar characteristic to them and relative to their times. Maybe it was because the majority of older men had fled, were imprisoned or had died.

Jean Cabanel witnessed a gathering of Camisards for worship in the woods – the Camisards were forced to hold their meetings in secret. He describes Occitan-speaking adult Camisards speaking in French – a language foreign to them, especially since they were uneducated.

I believe I saw at least fifteen people of one and the other sex speaking at different times under the inspiration. They were all speaking French and I am quite sure that some of these that I specifically knew, that did not know how to read, would not have had the ability to express themselves in such good French being outside of ecstasy.10

Jacque Dubois declared that sometimes the people under ecstasy spoke in foreign languages.

I have seen many people of one and the other sex who in ecstasy were pronouncing certain words that the assistants believed to be a foreign language. Afterwards, they that were speaking explained several times the meaning of those sayings which they had been uttered.11

What happened to the Camisards after this turbulent period is another story. One that can be found in the book,From a Far Country: Camisards and Huguenots in the Atlantic World, by Catharine Randall or the article found in Christianity Today’s website,Huguenots Driven Out of France.

—————————

Notes:

- The translations from the French are done by me with the helpful assistance of Anatasha Sullivan

- The actual digitized French texts relating to this work can be found at The Camisard Text on Speaking in Tongues

- For more information:

- Les Prophètes Protestants. Réimpression de l’ouvrage intitulé, Le Théatre Sacré des Cévennes, ou Régit des Diverses Merveilles. This is an updated 1847 French version of the original 1707 text by Maximilien Mission. The typography is much easier to read than the original.

- Virtual Museum of Protestantism gives a detailed look at Huguenot history

- Huguenot Prophecy and Clandestine Worship in the Eighteenth Century by Georgia Cosmos. I haven’t read it yet, but looks very interesting.

- Catharine Randall. From a Far Country: Camisards and Huguenots in the Atlantic World. Georgia, USA: The University of Georgia Press. 2009. Pg. 18

- Catharine Randall. From a Far Country: Camisards and Huguenots in the Atlantic World. Georgia, USA: University of Georgia Press. 2009. Pg. 17

- avait de grandes agitations de tout le corps, et particulièrement de la poitrine.

- Il parlait avec sanglots

- tomba dans des agitations

- My translation from Les Prophètes Protestants. Réimpression de l’ouvrage intitulé, Le Théatre Sacré des Cévennes, ou Régit des Diverses Merveilles. A. Bost. ed. 1847. Pg. 141

- My translation from Les Prophètes Protestants. Réimpression de l’ouvrage intitulé. Pg. 152-154

- Les Prophètes Protestants. Réimpression de l’ouvrage intitulé. Pg. 152-154

- My translation from Les Prophètes Protestants. Réimpression de l’ouvrage intitulé. Pg. 139

- My translation from Les Prophètes Protestants. Réimpression de l’ouvrage intitulé. Pg. 142

- My translation from Les Prophètes Protestants. Réimpression de l’ouvrage intitulé. Pg.154

Interesting . I heard a story from the Pasadena, Texas Assembly Of God church around 1965 as told by Rev. Joe Jordan. A small child was being dedicated to the Lord by his parents. The child was small enough to not have developed any speaking ability yet. While the child was being dedicated he began to speak fluently in another language. This church was famous for the supernatural gifts the Pastors had of tongues and interpretation. brothermel.com for further information on the modern day gift of speaking in tongues.