The protestant view of miracles from Martin Luther to the Church of England.

This is part 3 of a series surveying the doctrine of cessationism.

Part 1 was an introduction and a general summary. Part 2 gave a background to the medieval mindset that was highly dependant on the supernatural, magic and mystery in daily living. It also covered the re-examination of earlier christian history by prominent English leaders to demonstrate that miracles had ceased.

This series has a tertiary focus on the role of speaking in tongues within the cessationist doctrine. Those who adhere to a strong adherence to cessationism categorize tongues as a miracle, and since all miracles have ceased, the christian rite of tongues is no longer available. Any current practice is considered a false one.

This forces this series to shift away from the christian doctrine of tongues, and move into the protestant doctrine of miracles.

This article will demonstrate the Puritans were largely responsible for shaping the doctrine of cessationism through various means, especially the Westminster Confession. This doctrine may be the English Church’s most recognizable contribution to the protestant revolution throughout the world.

The Protestant De-Emphasis

One the most distinct differences between the early Protestants and Catholics was the concept of divine revelation. The Catholics believed in progressive revelation: religious belief and behaviour can evolve over the centuries. New doctrines can be added or subtracted. The channel by which this happened was through the symbol of miracles. God could express His present will to mankind through this agency. It could happen through an event, a saint, or institution. This allowed the church to include practices and beliefs such as the veneration of saints, mariology, purgatory, celibacy, additions to the Bible (the Apocrypha) and indulgences. The powers of church authority were given equal authority to that of Scripture through the confirmation of alleged miracles.

Early Protestants rejected the idea of progressive revelation whereby new doctrines and behaviors could be added. They believed in static revelation instead—a concept that limited miracles only to define doctrine from either the first – or at the latest fourth-century. After that, the age of doctrine development was closed. There were to be no additions or subtractions to the framework outlined in Scripture. Scripture was the final authority in christian affairs and cannot be overruled or added to by later miraculous revelations.

The question about how far miracles were limited after the formation of the church is the one that became the centre of attention in the protestant world.

The role and nature of miracles in the protestant church will now be closely examined.

Martin Luther

One of the most well-known names attached to the early Protestant movement is Martin Luther (1483–1546). His writings and sermons vacillated on this subject of miracles, though in the end he was a de-emphasizer. Specifically, he believed whatever miracles that did occur could not create or validate a new doctrine. Neither could it supercede Scripture. Philip M. Soergel, a specialist in medieval and early modern European history, looked into his attitude towards miracles and answered:

Luther’s statements held out the possibility that the “age of miracles” had ceased, but his praise of faith’s potentialities tended to undercut that conclusion all the same. This tendency–insisting on the one hand that the apostles were able to work miracles for a time only to establish the Church and on the other hand maintaining that faith has its own miracle-working power–continued to interact in Luther’s mature evangelical theology. The interplay betweeen these two notions prevented Luther from articulating a firm doctrine of the “cessation of miracles,” as it did for his later sixteenth-century followers as well. As in other areas of his thought, the Reformer proved to be cautious about making blanket pronouncements, since such judgements might presume to know the will of God and the workings of the Holy Spirit.1

For the curious, here are two quotes from his written sermons that show his vacillation on miracles.

-

The first, “Thanks be to God that we have no longer any need of miracles; the Gospel doctrine has been established by signs and wonders sufficient, so that no one has any cause to doubt them.”2

-

And in another sermon he contrarily wrote:

A person may called into the preaching office in one of two ways. The first one is directly from God, the other through His people, which is also simultaneously from God. Those called immediately must not be believed unless they are certified because their preaching is accompanied by miracles. That is what occurred in the case of Christ, and His apostles, whose preaching wast attested with accompanying signs. Then, when a preacher called in this way might come and say to you [Matthew 16], “God is speaking to you here. Receive the Holy Ghost,” as they must preach, you must then, of course, ask, “What sign do you give so that we can believe you? If it is only your words then we will pay no attention to them since you, from out yourself, could not say anything worth hearing. But if you work a miracle with it, then we will carefully examine what kind of doctrine you have, and whether or not you speak the Word of God.” . . .

Do not just believe people because of evidence they give when they attest to the spirit in them with signs and wonders. Do not only look at the fact that they are doing miracles, for the devil can also work miracles.3

It is noted how little Luther referred to the subject of miracles. Perhaps this may be a problem of an analysis done only in the English translations without referring to the original German. No comprehensive work by an authoritative writer so far has shown any disparity between the German and English in this area and so it must be assumed that Luther hardly addressed it.

Jean Calvin

Jean Calvin (1509–1564) was the administrative genius behind the early Reformation. What Luther started, Calvin structured. He added to the miracles debate with slightly more depth from Luther, but still fell short of being a hard cessationist.

The Catholic Church had criticized the Protestant movement as unsanctioned by God because it was never validated through the agency of miracles. Calvin countered this message by writing:

They are unreasonable when they demand miracles of us. For we are not inventing any new gospel, but we maintain as the truth that gospel confirmed by all the miracles which Jesus Christ and His apostles ever did. You could say that in this distinctive way they go beyond us, that they can confirm their teaching by continuous miracles which are being done up until today. But they claim miracles which are so frivolous or lying that they would undermine the spirit and make it doubt when otherwise it would be at peace. Yet, nevertheless, if these miracles were the most amazing and admirable one could imagine, they would have no value at all over against God’s truth, since by rights the Name of God should be hallowed always and everywhere, whether by miracles or by the natural order of things. Those who accuse us would have more semblance of cover if scripture had not warned us about the right use of miracles.”

. . . So we do not lack for miracles, which are most certain and not subject to ridicule. On the contrary, the miracles which our adversaries claim for themselves are pure tricks of Satan when they draw people away from the honor of their God to vanity.4

Nowhere here does he express the cessation of miracles, rather he outlined the abuse of it.

Some authors have quoted Calvin’s Commentary on the Gospel of John, 20:30-31 to express his support of miracles. However, he does not qualify his statement for or against modern day miracles. He does suggest that miracles do excite the mind to comtemplate God’s power. This could be construed as his condoning of miracles during his time. Let the reader examine the following text itself and see if this is true or not.

Although, therefore, strictly speaking, faith rests on the word of God, and looks to the word as its only end, still the addition of miracles is not superfluous, provided that they be also viewed as relating to the word, and direct faith towards it. Why miracles are called signs we have already explained. It is because, by means of them, the Lord arouses men to contemplate his power, when he exhibits any thing strange and unusual.5

It is not a strong statement that one can build a thesis on. The portrait one can draw from Calvin is a hesitancy to miracles and that one ought to be very careful. He aligns with the protestant mantra that miracles must not be used to supercede Scripture.

The Church of England and Miracles

The 1600s demonstrate the concept cycling from de-emphasism to cessationism, especially within the English realm.

The Church of England was officially formed in the 1530s after King Henry VIII was not granted a divorce from his wife, Catherine of Aragon, by the Catholic authorities. The initial institution had no stance on miracles and little to no anti-catholic sentiment. This was reflected in their confessions of faith developed in 1572 called the Thirty-Nine Articles.

The Church of England was pulled in many different directions concerning miracles in the next 150 years. There are four distinct, but interweaving themes; the Puritans, Latitudinarians, Rationalists, and the Presbyterians.

The Puritan Influence

This is the section where the doctrine of cessationism takes off. The Puritan influence on the Church of England, and its splinter groups were immense. Puritan thought may be one of the least studied or understood modes of thought in western literature. Though never a party, nor an independent religious sect, and no person to call as its historic leader, their impact was immense.

The Puritans were an activist movement within the Church of England that sought to rid itself of any catholic identity and zealously pursued for a greater purity in worship and doctrine. They allied later with the Scottish Presbyterians on many matters of doctrine including cessation of miracles. Their influence was at its zenith between 1642 to 1660. The public during this 18 year period was generally fatigued over the over-emphasis on Scriptural adherence, even on the smallest matters. There was a feeling that both the Churches of Scotland and England had traded the superstitions of Catholicism for the the rigorous enforcement of Scripture–a dry legalism that forced absolute obedience with little freedom of expression or ideas. This period was a time where the British Isles were broken into political, religious and military factions. King Charles II decreased the puritance prominence in 1660. He settled the internal warring factions in what was called the Restoration. The puritan movement was sidelined from active participation in the Church of England from that point on.

Puritan thinkers were strong proponents of cessationism, and it is their legacy that we owe this doctrine. This will be explained in further detail shortly.

The Presbyterians were a slightly later offshoot of the Scottish Protestant movement which held tightly to the teachings of Jean Calvin. The Scottish cleric, John Knox, a student of Calvin, ensured this tightly knit relationship. The movement especially gained momentum after the English Civil War in 1651 and the name Presbyterian began to be attached. In 1650 the Scottish Church created their first confession. It did not contain any reference to miracles.6 However, they did adhere to the cessationalist teaching found in the Westminster Confession earlier in 1646 (explained further down), and later became one of the louder proponents in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

The puritan influence is the more important one, because Presbyterians eventually adopted their line of thinking about miracles. The following is a brief outline of the puritan doctrine cessationism.

William Whitaker

William Whitaker (1547–1595) was an Anglican theologian and Master of St. John’s College, Cambridge. The Latin-English dictionary he devised and published is still commonly used by Latin students around the world today. More importantly to this discussion, he contributed to the first chapter on the Westminster Confession of Faith which contained the cessation clause.7 Whitaker firmly established the authority and position of Scripture over miracles and veneration.8

William Perkins

William Perkins (1558-1602) was a Cambridge educated cleric of the Church of England. He was a gifted orator and popular writer. Although he was a follower of Calvin, his works outsold Calvin by a significant margin inside England. He was staunchly conservative and dogmatic, but yet did not join the puritan ranks. His legacy was greatly esteemed by both the Puritans and Presbyterians. However, the degree of influence is a matter of scholarly debate.9

His writings clearly outline that a practicing Protestant should avoid any outward exhibitions of miracles for two reasons. The first one was that the expression would be too close to being Catholic. He made a clear connection between Catholicism, miracles, and the devil. This was Perkin’s primary reason for rejecting miracles in the system of christian faith.

Secondly, he drew lessons from the catholic aspiration for miracles and applied it human nature. He believed people seek to do wonders for personal or occupational gain. Both of these factors are outlined in his book, Discourse of the Damned Art of Witchcraft:

It were easier to show the truth of this, by examples of some persons, who by these means have risen from nothing, to great places and preferments in the world. Instead of all, it appeareth in certain Popes of Rome, as Sylvester the second, Benedict the eight, Alexander the sixth, Iohn the 20 and the twenties one, &c. who for the attaining of the Popedom (as histories record) gave themselves to the devil in the practice of witchcraft, that by the working of wonders, they might rise from one step of honour to another, until they had seated themselves in the chair of the Papacy. So great was their desire of eminence in the Church, that it caused them to dislike meaner conditions of life, and never to cease aspiring, though they incurred thereby the hazard of good conscience, and the loss of their souls.

The second degree of discontentment, is in the mind and inward man; and that is curiosity, when a man resteth not satisfied with the measure of inward gifts received, as of knowledge, wit, understanding, memory, and such like, but aspires to search out such things as God would have kept secret: and hence he is moved to attempt the cursed art of magic and witchcraft, as a way to get further knowledge in matters secret and not revealed, that by working of wonders, he may purchase fame in the world, and consequently reap more benefit by such unlawfull courses, then in likelihood he could have done by ordinary and lawful means.10

Perkins believed that since the Gospel has been established there was no further need for miracles at all.

Therefore if Ministers now should lay their hands on the sick, they should not recover them: if they should anoint them with oil, it should do them no good, because they have no promise.11

He continually attacked the Catholic Church on their continued abuse of miracles and how the age of miracles had passed:

This gift continued not much above the space of 200 years after Christ. From which time many heresies began to spread themselves; and then shortly after Poperie that mystery of iniquity beginning to spring up, and to dilate itself in the Churches of Europe, the true gift of working miracles then ceased, and instead thereof came in delusions, and lying wonders, by the effectual working of Satan, as it was foretold by the Apostles, 2. Thess. 2. 9. Of which sort were and are all those miracles (Pg. 239) of the Romish Church, whereby simple people have been notoriously deluded. These indeed have there continued from that time to this day. But this gift of the holy Ghost, whereof the Question is made, ceased long before.12

Perkins was reacting against both against Catholicism and superstition. These two entities promoted miracles through ceremony, rituals and recitation of specific words.13 Perkins did not realize the these three behaviours were instituted in the earlier church to correct the problem of selfish personal ambition through the agency of miracles.

It appears that the fourth-century church de-emphasized the individualized expression and moved it into corporate and symbols as a counter to this problem. The fourth-century church father John Chrysostom writings represent a shift into ceremony, rituals and institutional authority instead of the emphasis on an endowed person. Augustine, in the case of speaking in tongues, shifted the emphasis from a personal to corporate one.14 This observation is far from complete and needs more attention, but it holds important value for consideration.

Perkins logic is confusing. He allows for the devil to produce enchantments and sorceries that seem like miracles, albeit for diabolical purposes, but denies any alternative power of the church or the Christian to produce miracles.

His idea owns that no human can produce or be a direct causative agent for miracles. Instead, the ancient persons involved in administering a miracle were passive agents, a conduit that God used. The emphasis was on the agency not the person15 This forced Perkins to contemplate the miracles Jesus produced. If Jesus was part human, then how could He actively bring about miracles at His command? Perkins made an exception here. He described that Christ had a dual man/God nature. The miracles were not produced from the man nature, but normally from the God one. On the raising of Lazarus it was the combination of both.16

He expanded the definition of evil and satanic to any expressions of the catholic faith. This was consistent with many other protestant leaders.

James Ussher (1581–1656)

This scholar, theologian and cleric for the Church of Ireland (a member of the Anglican Church community) was best known for his work for dating the day of creation. He was a student of William Perkins.

Similar to Perkins, Ussher issued a direct attack on the Catholics and their supposed miracles with vehemence:

That seeing the Popes Kingdom glorieth so much in wonders, it is most like, that he Antichrist; seeing the false Christs and false Prophets shall do great wonders to deceive (if it were possible) the very Elect, and that some of the false Prophets prophesies shall come to pass, we should not therefore believe the doctrine of Popery for their wonders sakes, seeing the Lord thereby trieth our faith; who hath given to Satan great knowledge and power to work stranger things, to bring those to damnation who are appointed unto it.17

Ussher then concluded the above thought with this:

Are not miracles as necessary now, as they were in time of the Apostles?

No verily. For the doctrine of the Gospel being then new unto the world, had need to have been confirmed with miracles from heaven: but being once confirmed there is no more need of miracles; and therefore we keeping the same doctrine of Christ and his Apostles, must content ourselves with the confirmation which hath already been given.

What ariseth out of this?

That the doctrine of Popery is a new doctrine, which had need to be confirmed with new miracles; and so it is not the doctrine of Christ, neither is established by his miracles.18

The Westminster Confession

At the height of the Church of England’s puritan influence was the development and enactment of the Westminster Confession in 1646. The goal of this confession was to codify the protestant sects in England into a united system of faith. It still has force today in some religious jurisdictions.

The Westminster Confession has two articles important to miracles:

-

The first one was under the first section relating to the authority of Scripture where it states that God has ceased in further revealing his will through the written Word. What has been already accomplished in His sacred Word is final. There are no additions.19

The ceased word is very ambiguous and controversial. Garnet Milne in his excellent book, The Westminster Confession of Faith and the Cessation of Special Revelation: The Majority Puritan Viewpoint on Whether Extra-Biblical Prophecy is Still Possible summed up the interpretation of ceased as this:

An analysis of the writings of the Westminster divines reveals their pervasive commitment to a cessationism of a rather comprehensive kind, In their exposition of the key texts of Eph. 1:17-18, Heb. 1:1-2, and Joel 2:28-32/Acts 2:17, a large proportion of the divines contend that the possibility of further revelation has ceased, both for the purposes of doctrinal insight and for ethical guidances. They repeatedly contrast the role of Scripture with phenomena such as dreams and visions as means of divine communication, and argue that the latter modalities are firmly confined to the past.

From a range of other biblical texts the divine adduce further reasons as to why the church ought no longer expect revelation from a source outside of Scripture itself. Extra-biblical revelation is restricted to the eras of the patriarchs, prophets, and apostles. Special revelation for the governance of the church is said to have ceased. Warnings are issued against the inherent dangers of appeals to immediate inspiration, and the cessation of such revelation is linked to the cessation of miracles. Old Testament texts in particular tend to be read analogically. The Scriptures as a whole are presented and appealed to as the final supernatural revelation of God for all purposes.20

Although Milne properly addressed the puritan concept behind this word, the Westminster Confession was purposely ambiguous for those in the non-puritan ranks. The ambiguity of ceased allowed for a degree of flexibility in interpretation among the various protestant English factions that the Westminster Confession hoped to unite.

-

Secondly, this confession held that the Pope was the antichrist 21 though this has been revised in the most recent versions. Anti-Catholicism and their alleged false miracles were a source of unity among the various protestant branches.

The Westminster Confession of Faith set the standard for later English Protestant confessions such as the Savoy Declaration modified for Congregationalists in 1658, and the London Baptist Confession of 1689. They both contained the cessation clause.

Latitudinarians

Latitudinarianism was a phrase attached to a certain mode of thinking in the early Church of England. This was not a large movement, but their membership contained a considerable influence. Latitudinarians emphasized an alliance of science and religion and often were at odds against the more conservative and dogmatic puritan thinkers. The perception of miracles was approached clinically and in more rational, philosophical and scientific manners, but theoretically accepted. A strain of anti-catholicism and the rejection of their miracles as patently false connects them with the rest of the Church of England.

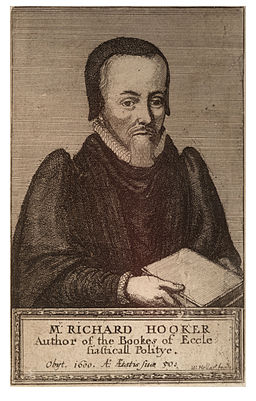

The major contributor to the formation of the the Latitudinarian movement was the Anglican priest and theologian, Richard Hooker (1554–1600). He did not address the problem of miracles at all. Although he had some doctrinal problems with Catholic theology, he wasn’t absolute and completely rejectionist of Catholicism either. His works were aimed more squarely against the conservative puritan faction of the Church of England whom he held were extreme in their views.

Western society owes an intellectual debt to the Latitudinarians such as the Protestant turned Catholic turned Protestant again and then accused by both sides of being a rationalist, William Chillingworth (1602–1664); the Archbishop of Canterbury John Tillotson (1630–1694); and the writer, philosopher and cleric Joseph Glanvill (1636–1680). Glanvill was an interesting thinker. He envisioned a future where mankind would be able to communicate throughout the world via the ether.

The late 1600s and early 1700s found the proponents of miracles from not from English theologians but from scientists such as the astronomer, mathematician, and physicist, Isaac Newton, and John Wilkins the founder of the oldest scientific community, the Royal Society.22 Both of these figures aligned closely with the Latitudinarians.

None of these leaders promoted the cessation of miracles.23

The Rationalists and Deists

Hooker not only influenced the Latitudinarians but his writings licensed others to use reason, commons sense, and intellectual inquiry in their religious pursuits. The explanation of the following people fall under the list belonging to the Church of England because everyone under English control belonged to it, whether they liked to or not, and were heavily influenced by their values. On the other hand, the conservative Church of England followers and break-away groups were often seriously critical of the following named people. They would not define them as representing the christian religion.

Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) was one of the philosophers who added to Hooker’s cry for reason. Hobbes stumbled through his idea of miracles and it is hard to decipher a clear position because of his semantics and wordiness. He does reaffirm the mantra that miracles had ceased.24 But on the other hand, he was very cautious about naming anything a miracle. He believed the layman was ignorant of the science behind any event and too easily fell into calling something a miracle. For example, the occurrances of nature which one does not understand was often considered a miracle. Secondly, Hobbes was concerned about those who faked miracles for public attention. All ideas of miracles should be put under the scrutiny of reason by the individual and the church. The natural outcome would be that there was a natural explanation that would ultimately exclude the concept of a miracle.25

The next entry inevitably leads to the framework on miracles built by the well-known philosopher and physician John Locke (1632–1704). This brilliant thinker, best known for his influence on the wording and structure of the American Constitution, found a way that comfortably balanced reason and religion in his writings.

His work, Discourse on Miracles (1706), demonstrated this skill. He believed in miracles but in an uncertain sense. What a miracle is to one person, may not be to another. It depends on a person’s grasp of universal laws and science. This matter of perception would be especially true in his time where the gap in scientific knowledge was so great and the understanding of human physiology was small. He believed that the amount of claims for miracles were far greater than the actual ones that have occurred. He follows Hobbes’ structure but softer in regards to religion. He set out some general rules for determining a divine miracle.26

The two most controversial and debated names on the topic of miracles is Conyers Middleton (1683–1750), and David Hume (1711–1776).

Conyers Middleton was a church historian who promoted the idea that miracles and signs were not necessary for defining christian truth, practice, or polity. The dispute against miracles and signs was the centerpiece in his, Free Inquiry, which was unique and highly controversial when it was first introduced. By applying common sense to principles of faith over mysticism, he sought to distance the protestant identity and authority from that of the Catholic Church. His opinions still resonate today.

Middleton does address the doctrine of tongues but it is limited. He fails to take in a larger corpus of ecclesiastical literature to draw his conclusions. By using such a small sampling, he could easily state that the gift of tongues died within the first century church and not have to wrestle with the likes of Pachomius, Augustine, or the historical context of the Corinthian tongues problem, which was not mystical at all, but a functional one. He slightly addressed Chrysostom’s texts to support his argument but further elaborates the subject when he published, An Essay on the Gift of Tongues but the work adds hardly anything new to the debate.

The more traditional theologians of the time spent considerable effort to refute his claims about miracles. For example, William Dodwell, a contraversialist, theologian, and minister, took it upon himself to refute Middleton with his book, A Free Answer to Dr. Middleton’s Free Inquiry. In doing so Dodwell was conferred a Doctorate of Divinity by Oxford.27 However, his refutation failed to produce the desired results. Middleton’s work has perpetuated while his has fallen into obscurity.

Middleton’s work had such a great impact that the legendary evangelist John Wesley saw the need to refute in a letter to Dr. Conyers Middleton. Wesley’s response is largely forgotten in the annals of history, being powerfully overshadowed by the legend of Free Inquiry whose primitive arguments still stand, and have been greatly expanded upon by cessationists and scholars living today.

For further information see: Conyers Middleton and the Doctrine of Tongues

David Hume (1711–1776) is a hard one to describe. His opinions were not representative of the church but yet he used the symbols and language of the church and christian faith.

This distinguished thinker has to be included because his influence was so widespread. He is one of the pillars of western philosophy. To ignore his thoughts on the subject would be unacceptable.

Hume was sceptical of any miracle and promoted the idea that believing in anything unsubtantiated is foolish. He accepted that there was a chance for a miracle to occur, but only if it has been properly examined. In this case, he believed not one has been properly substantiated throughout history using a valid procedure to verify such a claim. He totally rejected the claim of a person or group testifying of the fact. He wanted factual evidences over perception. This lack of facts led him to conclude that christian miracles do not exist, and the whole christian story is based on fiction. “whoever is moved by Faith to assent to it, is conscious of a continued miracle in his own person, which subverts all the principles of his understanding, and gives him a determination to believe what is most contrary to custom and experience.”28

His ideas were picked up by Baden Powell (1796–1860) – a mathematician and a priest of the Anglican Church. His articulation of faith and science was introduced in a more open environment than that of Hume. He believed that miracles was but a definition by mankind to describe a natural event not understood. Every miracle can be explained by natural means, except that mankind has yet to understand the mechanics that caused it. People of higher intelligence, because of their insights into science and the laws of nature, found miracles much less common than the layperson.29

There are more rationalists/deists of England that can be drawn from but this is sufficient for the reader to understand. They set the seeds of intellectual thought that lives with us today. The role of the miraculous and the supernatural have been relegated to matters of faith and not physical reality. The issue of tongues fit into the category of a faith event that was categorized in an unexplainable psychological condition that one day will be understood as science advances.

- Next: Cessationism, Miracles, and Tongues: Part 4 Cessationism from the 1800s until today.

- Previous: Cessationism, Miracles, and Tongues: Part 2 A medieval background to magic and miracle along with an overview of the Protestant view of miracles in the early church.

- Philip M. Soergel. Protestant Imagination: The Evangelical Wonder Book in Reformation Germany. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2012. Pg. 41

- Martin Luther. Sermons on the Gospels For the Sundays and Principal Festivals of the Church-Year. No translator given. Columbus: J. A. Shulze. 1884. Pg. 246

- Martin Luther. Festival Sermons of Martin Luther. Translated by Joel R. Baseley. Michigan: Mark V Publications. 2005. Pg. 3-4

- Jean Calvin. Institutes of the Christian Religion: The First English Version of the 1541 French Edition. Translated by Anne McKee. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. 2009. Pg. 11-12

- Jean Calvin. Commentary on the Gospel of John. Vol. II Translated by William Pringle. Edinburgh: Calvin Translation Society. 1847. Pg. 281

- http://www.creeds.net/Scots/

- Garnet Milne. The Westminster Confession of Faith and the Cessation of Special Revelation: The Majority Puritan Viewpoint on Whether Extra-Biblical Prophecy is Still Possible. Great Britain: Paternoster. Reprinted by Wipf and Stock Publishers. 2008. Pg. 52

- This was concluded by an examination of his work, A Disputation on the Holy Scripture Against the Papists, especially Bellarmine and Stapleton. Cambridge: The University Press. 1849. There may be better information in another work, though I haven’t seen it yet

- Garnet Milne. The Westminster Confession of Faith and the Cessation of Special Revelation: The Majority Puritan Viewpoint on Whether Extra-Biblical Prophecy is Still Possible. Great Britain: Paternoster. Reprinted by Wipf and Stock Publishers. 2008. Pg. 50

- Updated English copy from William Perkins. A Discourse of the Damned Art of Witchcraft. Cambridge: Cantrell Legge. 1618. Pg. 10-11

- Updated English copy from William Perkins. A Discourse of the Damned Art of Witchcraft. Cambridge: Cantrell Legge. 1618. Pg. 232

- Updated English copy from William Perkins. A Discourse of the Damned Art of Witchcraft. Cambridge: Cantrell Legge. 1618. Pg. 238

- As described in the book: Transactions of the Royal Historical Society. Sixth Series. Vol. VIII. David Eastwood ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1998. Pg. 176

- A further look into this shift can be found in the following article Chrysostom on the Doctrine of Tongues. The link will take you to the subheader on the topic.

- William Perkins. A Discourse of the Damned Art of Witchcraft. Cambridge: Cantrell Legge. 1618. Pg. 243

- William Perkins. A Discourse of the Damned Art of Witchcraft. Cambridge: Cantrell Legge. 1618. Pg. 16

- James Ussher. A Body of Divinity or the Sum and Substance of Christian Religion. London: R. J. for Jonathan Robinson, A. and J. Churchill, J. Taylor, and J. Wyatt. 1702. Pg. 392

- IBID James Ussher. A Body of Divinity or the Sum and Substance of Christian Religion. Pg. 392

- http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/creeds3.iv.xvii.ii.html

- Garnet Milne. The Westminster Confession of Faith and the Cessation of Special Revelation: The Majority Puritan Viewpoint on Whether Extra-Biblical Prophecy is Still Possible. Great Britain: Paternoster. Reprinted by Wipf and Stock Publishers. 2008. Pg. 145

- Section VI http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/creeds3.iv.xvii.ii.html

- Stephen Paul Foster. Melancholy Duty: The Hume-Gibbon Attack on Christianity. NL: Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht. 1997. Pg. 101 – the author is presenting this from M. Burns, The Great Debate on Miracles: From Joseph Glanville to David Hume.

- For more information on Latitudinarians see Joseph Waligore’s, “Christian deism in eighteenth century England” as found in the International Journal of Philosophy and Theology. 2014. Vol. 75, Issue 3. Pg. 11

- Thomas Hobbes. Leviathan Chapter 32 “Seeing therefore miracles now cease, we have no sign left whereby to acknowledge the pretended revelations or inspirations of any private man;”

- Leviathan Chapter 37. “For in these times I do not know one man that ever saw any such wondrous work, done by the charm or at the word or prayer of a man, that a man endued but with a mediocrity of reason would think supernatural:”

- The Works of John Locke in Nine Volumes. Vol. 8. 12th ed. London: C. and J. Rivington. 1824. Pg. 262ff.

- http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Dodwell,_William_%28DNB00%29

- David Hume. An Enquiry Concerning the Human Understanding. L. Selby-Bigge, ed. London: Oxford University Press. 1894. Sec. X, Part II (101) Pg. 131

- Essays and Reviews: “On the Study on the Evidences of Christianity,” by Baden Powell. London: John W. Parker and Son. 1860. Pg. 107