Pentecostal solutions to the missionary tongues and gibberish crisis.

Early Pentecostal excitement and enthusiasm for missionary tongues in foreign nations failed. They also had a serious challenge on the home front. The general public mocked them for speaking gibberish. These circumstances created an urgent need to build a Pentecostal apologetic for their speaking in tongues.

Pentecostals mulled over a variety of solutions to solve these theological challenges along with asserting their credibility. They had the choice of admitting they were wrong but did not. Many chose to ignore that the missionary tongues crisis ever occurred. Others shifted the emphasis to writing and singing in tongues. Some early leaders chose to make a distinction between utterance and the gift of tongues. The emphasis on utterance kept the definition ambiguous and quasi-related to language and easier to defend than the traditional definition found encapsulated in the term gift of tongues. Praise and adoration became a feature of Pentecostal tongues, and then later, a heavenly or private prayer language broadened the definition. Glossolalia also transferred in from academia and was given a Pentecostal sense.

This summary draws from a wide range of early Pentecostal newspapers, periodicals, and correspondence. The rest of this document substantiates these claims.

Special notes are given where there are references to publications and authors from the Higher Criticism perspective—a popular school of thought that entirely dominated the primary and secondary source books on matters of the Christian faith. This connection is important because, as will be shown, Higher Criticism heavily influenced the final Pentecostal solutions to the tongues crisis.

The redefinition process started almost simultaneously after speaking in tongues became fashionable in 1906.

Table of Contents

Admit they were wrong

There is no publication or discussion in early Pentecostalism that gives this solution as an option. Donald Gee, one of the major Pentecostal leaders in the mid-1900s, did call missionary tongues “mistaken and unscriptural”1 By this point, it did not matter and had no impact on the movement, as the redefinition had already occurred.

Ignore the Problem

A prevalent theme in Pentecostal histories was to ignore that any problem existed about the nature and practice of speaking in tongues. No transparent discussion recognizes the tension throughout early Pentecostal literature. Rather, the tongues doctrine shifted into new semantics without any formal process.

This especially can be found with the important early Pentecostal editor, writer, and pioneer, Stanley Frodsham.

Mr. Frodsham first encountered the Pentecostal movement while a young man in England. His first personal encounter with speaking in tongues happened at A. A. Boddy’s church in Sunderland, England—an early British based Pentecostal hotbed. Frodsham then started a religious periodical out of his hometown, Bournemouth, England, called Victory. He later moved to the United States and was the editor for the Assemblies of God magazine called the Pentecostal Evangel–one of the largest Pentecostal denominations in the United States. His involvement with Pentecostalism, along with his editing and writing numerous compositions over the decades, gave him a quasi-official status for creating an early biography of the movement.

His book“With Signs Following: the Story of the Pentecostal Revival in the Twentieth Century,” was once the definitive book on anything Pentecostal by a Pentecostal. First published in 1926 and revised many times, even after 1946, is excellent and well documented–likely the best of any early Pentecostal histories. The first 17 chapters of the book document people who were miraculously speaking in foreign languages, and then an unexplained shift occurs in the last portion of his writing. At the end of the book, he concludes that Christian tongues are a secret speech, something between a man and God.2 He never delved into what necessitated or caused this change.

One of the most popular and well-known Azusa missionaries, A. G. Garr, also promoted the same approach. He was presumed to have the divine ability to speak in Bengali but, upon arrival, did not. He never took the time to ponder the problem greatly and was happy with the alternative blessings he encountered.3

The grassroots Renewalist movement (Pentecostal, Charismatic, and Third Wavers) carry on this tradition and do not recognize the theological crisis created by missionary tongues in the early days.

This has been a prevalent approach.

Utterance vs. Gift of Tongues

New data required a reworking of this section and, due to the increase in size, is now a separate article, Utterance versus the Gift of Tongues.4

Writing and Singing in Tongues

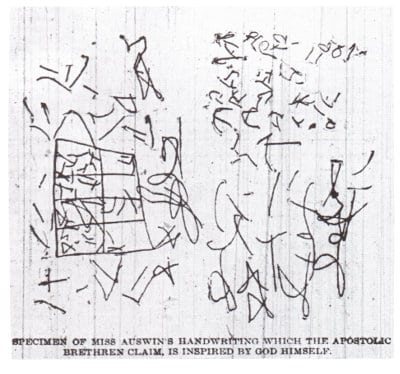

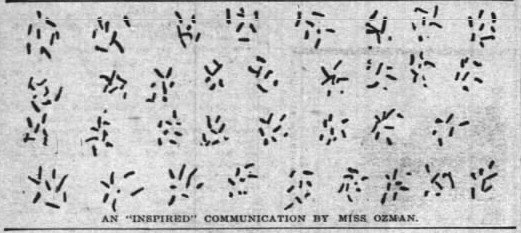

The missionary tongues emphasis is dominant, but the idea of writing in tongues also has some influence. The Irvingites had a demonstration of this writing in tongues doctrine in the 1830s. Then, in the early 1900s, one of Charles Parham’s students, Agnes Ozman, was credited with writing in tongues. A popular Azusa inspired leader, Lillian Garr, also strengthens that this was a frequent practice.5

The above sample is from James Goff’s Fields White Unto Harvest: Charles F. Parham and the Missionary Origins of Pentecostalism.

The sample below, found in the the newspaper, The Inter Ocean, Chicago, (Illinois. January 27, 1901. Pg. 37). It is different in style than the above. Any explanation about the discrepancy is unknown.

The appearance of writing in tongues shows that missionary tongues was not entirely absolute and there was a subculture that had other traditions developing.

Singing in tongues is unique to the Pentecostal movement. The Apostolic Faith Newspaper (Portland) described it in this way: “. . .One of the manifestations that followed Pentecost was the heavenly singing by a chorus of voices in supernatural sweetness and harmony. It was melting—wonderful. Praise God, many missions have had it since then. The song is inspired, it is an anointing of the Spirit. God gave new voices to old men and women and to people who had never been able to sing, and to those that had lost their voices.”6

Frank Bartleman described his Azusa experience as a new song and described the environment in musical terms. He first described the event as a linguistic miracle and then described a parallel experience as a personal emboldening to sing. “I felt after the experience of speaking in “tongues” that languages would could come easy to me. And so it has proven. And also I have learned to sing, in the Spirit. I never was a singer, and do not know music.”7

Writing and singing in tongues is symbolic for Pentecostals to channel feelings of an inexpressible joy. A 1916 edition of the Weekly Evangel described it as such: “He that speaketh in an unknown tongue speaketh not unto men but unto God.”–(I Cor. 14:2) The language of which the apostle is here speaking seems to have been of a very peculiar sort–an unintelligible vocal utterance, that which is often manifested at this present day, in great spiritual revivals. We are constituted that when there rises up in our souls a strong rush of tender emotions we feel utterly incapable to put them into words. If expressed at all they can only be in the quivering lip, the gleaming of the eye and the convulsive chest. The groans, the sighs, the rapturous shouts cannot be interpreted.”8

There may be much more to this speaking in tongues genre but there is very little historical literature. It may have been passed down through oral rather than literary traditions.

Tongues as an expression of praise and adoration

The Apostolic Faith newspaper adds to the utterance doctrinal narrative. When one utters it then converts into praise and adoration:

Those who speak in tongues seem to live in another world. The experience they have entered into corresponds exactly with that which is described in the 10th chapter of the Acts. The tongues they speak in do not seem to be intended as a means of communication between themselves and others, as on the Day of Pentecost, but corresponds more closely with that described in the 14th of 1. Corinthians, 2nd verse, and seems to be a means of communication between the soul and God. They do not speak in tongues in the assembly, but when in prayer; they become intense in their supplication; they are apt to break out in the unknown tongue, which is invariably followed by ascriptions of praise and adoration which are well nigh unutterable. The writer has about concluded that it is the “new tongues” spoken of in Mark xvi. 17 as one of the signs which are to follow them that believe, rather than the “Gift of tongues” which all evidently did not possess.9

The Bridegroom’s Messenger cites the highly respected Protestant-German academic Philip Schaff. They posit Schaff’s History of the Christian Church as an authority on how tongues is an avenue of praise and adoration:

The glossolalia was here as in all cases where it is mentioned, an act of worship and adoration, not an act of teaching or instruction which followed afterwards in the sermon of Peter.10

The article further reinforces this fact by quoting more from Schaff. The following citation especially adds to the Pentecostal idea of tongues as praise and worship.

It was an act of self devotion, an act of thanksgiving, praying, singing within the Christian congregation by individuals who were wholly absorbed in communion with God, and gave utterance to their rapturous feelings in broken, abrupt, rhapsodic, unintelligible words. It was emotional rather than intellectual. * * * * the language of the spirit or of ecstasy as distinct from language of the understanding.11

In 1909, William Manley, another participant directly blessed at the Azusa Street church, and well known as an evangelist, was the editor for an article with an unnamed author in his Household of God periodical that concerned tongues as language of praise and thanksgiving. The title was “Tongues: Their Nature and Use According to the Commentators”. The article compiled a list of books and commentaries to prove these two facets; purposely shifting the emphasis away from foreign languages.12

A previous edition of this article stated that tongues as adoration and praise was a major tenet, especially today. This statement was found incorrect. Tongues as an expression of adoration and praise is one of the many Pentecostal additions to the christian doctrine of tongues but not a definitive or dominant one.

Tongues as a Heavenly or Private Prayer Language

The shift from missionary tongues to utterance allowed the definition to move into a new direction. One of the effects of this transition allowed the concept tongues as a heavenly devotional language—a language of men and angels. Most mixed this concept with the traditional one of foreign languages believing that the definition allowed for either to happen.

The first one was posted on April 22nd, 1916 for the “interest of the Assembly of God” on the nature of speaking in tongues.

This is not a gift of different languages as some have believed, but is an emotional or heavenly language, in which the speaker speaks only to God.13

The author then supports his claim from the Pulpit Commentary that it was “an unintelligible vocal utterance,” and that it was sometimes a human language, others heavenly or angelic ones. 14

Two months later, another article was posted that credited its teaching from A. A. Boddy and the Pentecostal movement in England. There was a heavy emphasis on Conybeare and Howson’s Life and Epistles of St. Paul,” and Philip Schaff’s “Apostolic Church”. With these evidences the author included a double answer that integrated both the old and new definitions:

We see that the belief that the gift was for the preaching of the Gospel to foreigner, is unfounded. Foreign people did certainly hear their own languages on the day of Pentecost (the disciples were not, however, on that occasion, preaching the Gospel but magnifying God–the common use of the gift) therefore the Spirit must have sometimes given a known language.15

A 1920 edition of their publication acknowledged the ability to divinely speak a foreign language but more encouraged the personal aspect;

“With an understanding of the private use of the gift of tongues as a medium of expressing the heart’s deepest emotions, a greater field of usefulness opens before us, and Christian believers should have a greater interest in being filled with the Spirit and power for the accomplishing of divine work in the world than they have in merely—for their own comfort and satisfaction–getting rid of a troublesome inward disposition.”16

A writer by the name of Herman L. Harvey weighed in on the subject for Aimee Semple McPherson’s, Bridal Call: Western Edition and he too vacillated on the definition. He gave more emphasis on the personal expression as a human, angelic or prayer language and did not believe speaking in tongues was for missionary activity. He cautioned about an unspecified group in California (clearly referring to the Azusa Street revival) who had made a “sad mistake,”17 for promoting such a doctrine.

Tongues as Glossolalia

Even though the early Pentecostal followers were fond of Historical Criticism as it related to speaking in tongues, they hardly embraced the word glossolalia as a term that described their experience. There are some brief moments that surprise such as the Bridegroom’s Messenger (1909) that first quotes Schaff and then adds that the glossolalia at Pentecost was an act of worship and adoration, not a miraculous speech for the conversion and instruction of the masses.18 The writer understood the word close to its original intention, but this was not always the case. A writer named B. F. Wallace wrote in a 1916 periodical and defined glossolalia as speaking miraculously in a foreign language.19 Another account in 1920 states it can be declaring the works of God or uttering real languages on earth.20

In 1947, Donald Gee who is considered one of the fathers of the Pentecostal movement went so far as to call tongues ecstatic speech, but he did not go so far as to call it glossolalia. However, it appears to be the same thing to him. As previously noted, he taught that the view of early Pentecostals on missionary tongues was “mistaken and unscriptural”21 He then clarified the current Pentecostal definition on tongues: “From the data presented to us in the Scriptures, it seems clear that the gift of tongues consisted of a power of more or less ecstatic speech, in languages with which the speaker was not naturally familiar.”22

Glossolalia does not appear to take any serious usage in the Pentecostal realm until about the 1960s. The Pentecostal Evangel Magazine starts to use it as an abbreviation for speaking in tongues. In a 1962 issue it related about a Lutheran outbreak and described it as a “. . .“spiritual speaking,” known among theologians as “glossolalia” goes back to Christ’s Apostles. . .”23 The Magazine produced a special edition in 1964 with an article promoting glossolalia,24 and in the same year one more article and formation of a glossolalia archive occurred. The first one was a sort of clarification which avoids defining the very nature of tongues:

You may wonder, “what is meant by the word ‘Glossolalia’? It is a theological term applied to the practice of speaking with other tongues. . . it is as old as the Bible. Back in the days of the apostles (over 19 centuries ago) the followers of Jesus experienced glossolalia.25

The second one was the Assemblies of God announcement that they were setting up a “depository of writings on glossolalia (speaking in tongues)” at their main headquarters.26

A current popular Pentecostal leader, Rev. Heidi Baker, wrote a thesis entitled Pentecostal Experience: Towards a Reconstructive Theology of Glossolalia in 1995. She branded speaking in tongues as glossolalic prayer. An idiom which she described as an “embodiment and manifestation of God’s real presence to the Pentecostal community and the Church in our world. . . Pentecostal glossolalic prayer may be seen as God’s supernatural union with a person in a pre-conceptual, contemplative way and as an “incarnation” of this in a certain person’s life.”27 I have never heard this being used by a lay Pentecostal follower, preached from the pulpit, nor in any other Pentecostal literature. Baker was attempting to wrap a comprehensive philosophical framework around tongues and wanted to retain the Pentecostal distinctive while doing so. She failed to see the earlier connection between higher criticism or the early development of the word glossolalia when she built her argument. By ignoring or unaware of the antecedents, she demonstrates how thoroughly integrated the higher criticism influence has become. It is part of the DNA of Pentecostal experience and no longer questioned.

Early Pentecostal Tongues builds on a previous series that focused on the origins of glossolalia doctrine in the early 1800s called The History of Glossolalia. The emphasis of the original series was how the concept of glossolalia overtook the traditional definition and became the only option in most primary, secondary and tertiary source materials produced after 1879. As will be shown, the dominance of Higher criticism in the publication realm helped shape the framework for Pentecostal tongues as well.

Next: Pentecostals, Tongues, and Higher Criticism. The connection between early Pentecostalism and the writings of Higher Criticism authors Schaff, Farrar, Conybeare and Howson and a few select others.

For more information see the Early Pentecostal Tongues series.

- The Pentecostal Movement: A Short History and An Interpretation for British Readers. NL. NP. 1941.

- Stanley Howard Frodsham. With Signs Following: the Story of the Pentecostal Revival in the Twentieth Century. Missouri: Gospel Publishing House. 1946. Pg. 269

- see Garr’s Missionary Crisis on Speaking in Tongues for more information.

- Please do not use citation from any previous version of this article under the subheader of Utterance vs. Gift of Tongues. There was one important revision along with many additions to the separate article. One may notice some overlap in copy between Utterance versus Gift of Tongues and this one. Such outcomes occur when articles require splitting.

- The Apostolic Faith Newsletter. April 1907. Vol. 1. No. 7. Pg. 1

- The Apostolic Faith (Portland) July and August, 1908. Vol. II. No. 15

- Frank Bartleman. How Pentecost came to Los Angeles. NP. 1925. Pg. 74ff

- “Speaking in an Unknown Tongue” by John S. Mercer. Weekly Evangel. April 22, 1916. Vol. 136. Pg. 6

- Apostolic Faith Newspaper. June to September 1907. Vol. 1. No. 9. Pg. 2

- The Bridegroom’s Messenger. Jan. 15, 1909. Vol. 2. No. 30: Schaff’s History of the Christian Church, Vol. 1, Page 230

- The Bridegroom’s Messenger. Jan. 15, 1909. Vol. 2. No. 30: Schaff’s History of the Christian Church, Vol. 1, Page 235

- Their is no digital repository for Household of God articles and I haven’t found a physical location of any archived material. However, a reprint can be found in the Bridesgroom’s Messenger in the January 15th, 1909 edition of Bridegroom’s Messenger. Vol. 2. No. 30

- “Speaking in an Unknown Tongue” by John S. Mercer. As found in The Weekly Evangel. April 22, 1916. Vol. 136. Pg. 6

- IBID The Weekly Evangel. April 22, 1916. Vol. 136. Pg. 6

- The Weekly Evangel. June 3, 1916. No. 142. Pg. 4

- The Pentecostal Evangel. April 17, 1920. Nos 336 and 337. Pg. 7

- The Bridal Call: Western Edition. Los Angeles: The Bridal Call Publishing House. II, April Number 11

- Bridegroom’s Messenger. Jan. 15, 1909. Vol. 2. No. 30

- Weekly Evangel. April 8, 1916. No. 134

- Pentecostal Evangel. April 17, 1920. Nos. 226 and 337. Pg. ??

- The Pentecostal Movement: A Short History and An Interpretation for British Readers. NL. NP. 1941.

- Donald Gee. Concerning Spiritual Gifts. Missouri: Gospel Publishing House. 1972. Pg. 62

- Pentecostal Evangel. Nov. 18, 1962. Pg. 28

- Pentecostal Evangel. March 29. 1964. Pg. 18

- Pentecostal Evangel. April 26. 1964. “Speaking with Other Tongues.” Pg. 9

- Pentecostal Evangel. Nov. 1, 1964. Pg. 6

- Heidi Baker. Pentecostal Experience: Towards a Reconstructive Theology of Glossolalia. Thesis. Kings College, University of London. 1995. Pg. 5

Praise the Lord, Charles, for your excellent articles!

You write, “Tongues as an expression of adoration and praise is one of the many Pentecostal additions to the christian doctrine of tongues…”

It’s unclear what you mean. Surely the new converts speaking in tongues at Cornelius’s house were praising God in those tongues (languages)!

Do you mean instead that it’s a Pentecostal addition to the Christian doctrine of the *gift* of tongues mentioned by Paul?

The Pentecostal addition of the language of adoration and praise was introduced in the early 1900s to the Christian doctrine of tongues. You are correct that the converts in Cornelius’ house were giving adoration and praise in their language. Pentecostals though believe their adoration and praise is a special language that may or may not be human language. It can be intelligible or incomprehensible with its own improvised format and output.

The Gift of Tongues Project findings discovered that the gift of tongues referred by Paul had no connection with Pentecost. In fact, its origin is found in the Jewish liturgy which had a defined structure of speakers and interpreters. There was nothing miraculous in this rite. Jewish history, the Christian Father Epiphanius, and the Latin-based Ambrosiaster text make this connection. See the Gift of Tongues Project section on Corinth for more information.