Examining the influence of the Irvingite movement on the birth of Pentecostalism.

The London-based Irvingite movement revived the supernatural expressions within the church body and inspired a new framework for Christian living that reverberated throughout the Western world.

It makes one wonder, if there was no antecedent of the Irvingites in the 1830s, would there have been a Pentecostal movement?

A factual investigation reveals that the Irvingites were a major precursor to the Pentecostal movement. The similarity between the events that happened in Topeka, Kansas, under the leadership of Charles Parham and those of the Irvingites were too close to conclude as accidental. This statement is controversial. Many scholars and Pentecostals would disagree.

The rest of the article is devoted to substantiating this correlation and the controversies surrounding this question. Particular attention is paid to the transfer and evolution of the Christian doctrine of tongues.

Table of Contents

- Scholars on the Irvingite/Pentecostal Connection

- Pentecostal Interpretation of the Irvingites

- Heidi Baker

- Early Pentecostal Literature

- T. B. Barratt

- A Summary on the Scholary/Pentecostal Connection

- Four Major Pillars on the Transmission of Irvingite Doctrines

- Conclusion

Scholars on the Irvingite/Pentecostal Connection

The majority of scholars believe there is some connection but sustain that there is no direct historical evidence to substantiate a strong one. There are varying attempts, some come closer while others remain aloof.

Derek Vreeland

Derek Vreeland, a minister, academic, Emerging Charismatic, writer, and researcher produces one of the best thought-out works on the Irvingites.1 His research and structure have highly influenced the outcome of this article.

He traced a connection but then towards the end, pulls back on his assertion.

The life and ministry of Edward Irving—although historically disassociated from the Pentecostal movement—is worth the attention of scholars, pastors and thoughtful Christians who desire the life of the Spirit and the rightly divided word of truth.2

Gordon Strachan

Gordon Strachan, who was a controversial Church of Scotland minster and author of a popular Edward Irving biography called, The Pentecostal Theology of Edward Irving, created an odd connection. He admits commonalities between the two but extends that Pentecostals and Irvingites were “ignorant of each other’s existence.”3 He then proceeds with the rest of the book to build a portrait of Irving as a foremost Pentecostal forerunner. The reader should note that Strachan hailed from the same region that Edward Irving was born and raised. There may be some nationalist sentimentality in his connection.

Walter J. Hollenweger

Walter J. Hollenweger wrote two books, The Pentecostals, and, Pentecostalism: Origins and Developments Worldwide, which are primary source works. He sidelined any direct influence, and leaves the Irvingites as a footnote in his historical analysis.4

D. William Faupel

D. William Faupel, an Assemblies of God minister turned Episcopalian, teacher, librarian, and foremost authority on Pentecostal history, dove into the connection controversy. He emphasizes the connection passed through John Alexander Dowie. (More on Dowie later on.)

Strachan’s assertion that the movements were ignorant of each other is an obvious inaccuracy. The early Pentecostal literature often points to Irving as one of those who spoke in tongues. On his major claim, however, Strachan has a stronger case. To date no evidence has been set forth to demonstrate a historical link between the two movements.

The parallels to Irving to Dowie are even stronger. In my judgement, Dowie links the Irvingite movement to Pentecostalism. There is no hint of this in the Dowie sources available. Dowie himself appears never to have made reference to Irving. This fact, in itself, is not surprising. Dowie never acknowledged receiving anything from anyone. He never admitted his dependence on the Mormons for his teaching on polygamy, for example, though this was widely known by his disciples.5

His comment that early Pentecostal literature referencing Irving speaking in tongues is unqualified. Personal perusal of Pentecostal literature so far does not corroborate such a claim. Also, Dowie did make a reference to the Irvingites.

Larry Christenson

Larry Christenson, the late Charismatic-Lutheran leader who was highly influential in the Charismatic renewal movement, took a middle ground, ineffectively waffling between both sides:

The correlation between pentecostalism and the Catholic Apostolic church suggests the possibility that both movements, independently of one another, apprehended a common area of truth. The points of comparison between the two movements do not root out of a connection in history, but out of a common origin beyond history. The cluster of similarities is neither causally related nor is it accidental; it is a leitmotif which accompanies the historical manifestation of certain characteristics or potentialities which lie resident in Christ and His Body.6

Pentecostal Interpretation of the Irvingites

Heidi Baker

A well-known contemporary Pentecostal leader, Heidi Baker, believes that some Pentecostals sideline any earlier influence on their movement. This global statement would include the Irvingites and the reason why there is so little data to make any connection. Her concept minifies what is likely a greater percentage holding to this conviction. In her PhD thesis, Pentecostal Experience: Towards a Reconstructive Theology of Glossolalia, she wrote:

It should be noted again that some Pentecostals would disagree with any attempt to trace the historical roots of the movement because they believe that the Holy Spirit directly descended on their movement after nineteen comparatively subdued centuries, just as he came on the first day of Pentecost.7

Early Pentecostal Literature

Most early Pentecostal magazines and newsletters cite the Irvingites as brief historical quotes without any idea of inheritance. There was no attention given to Irving or his church as a framework for Pentecostal theology or practice.8

There are a exceptions. One early Pentecostal in particular, Max Wood Warhead, was both nostalgic and critical of the Irvingites. They were a lesson on what not to do:

It is instructive to trace the causes which led to its downfall. In 1833 Irvingites, having been driven out of various denominations, organized themselves into a new sect called The Catholic Apostolic Church whose ecclesiastical system included apostles, angels, elders, deacons and evangelists. Not long after the formation of this new sect the spirituality of this body of people began to decline. Under the tyranny of an ecclesiastical system those in authority began to suppress the prophetic utterance. . . In a word, ecclesiasticism and ritualism crushed and chocked the very life out of the Pentecostal Movement of eighty years ago.9

T. B. Barrat

T. B. Barratt, a Norwegian pastor with British roots and one of the founding members of Pentecostalism in Europe, had a different idea of the Irvingites. His perception of the Irvingites demonstrates there was not a universal interpretation of the Irvingite event by this time.

He thought they spoke miraculously in foreign languages. In his publication, In the Last Days of the Latter Rain, he was reacting against an unknown source. A person who posited that tongues were a language of ecstasy in the earliest church and a few centuries later changed it to mean exclusively the miraculous endowment of a foreign language. Barratt used the Irvingites as an example to counter this notion.10 Although Barratt did not name the person, it was a theological position established by the German theologian Augustus Neander.11

As a response to the Neander theory, he wrote:

What, therefore, in Irving’s day, might have appeared to outsiders “a jargon of mere sounds” or “gibberish,” was nevertheless a real language, spoken somewhere, but interpretation was necessary in order to appreciate it. This experience all have passed through, who have travelled among foreign nations or among heathen nations, whose language they have not known. It sounded often like “gibberish” to them.12

His reference to the Irvingites suggest that he was not familiar with them. He understood this movement as miraculously speaking in a foreign language and unaware that their definition of unknown tongue was different.13

A Summary on the Scholary/Pentecostal Connection

The traditional Pentecostal position needs careful consideration. Those who practice a devotional reading style with a rigid adherence to a Biblical framework could naturally come to the same conclusion as the Irvingites. An outside antecedent is not necessary for a modern Pentecost to happen. Therefore, it is theoretically possible that the Pentecostals were hardly aware of the previous Irvingite history.

The limited relationship merely connotes to Pentecostals a historical trajectory that miracles and tongues were possible.

Lay leaders and followers were likely unaware of the connection. The following demonstrates key parties were acutely aware. They incorporated and evolved the Irvingite legacy to various degrees.

Four Major Pillars on the Transmission of Irvingite Doctrine

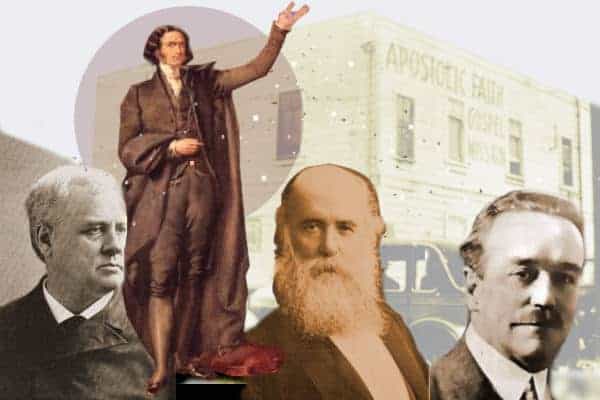

A . J. Gordon, A. B. Simpson, John Alexander Dowie, and Charles Parham were selected by Derek Vreeland in his book, Edward Irving: Preacher, Prophet and Charismatic Theologian, as key sources for the transmission of the Irvingite legacy. There is no disagreement with this selection. These persons are listed in detail below with added material, comparisons, and explanations on top of what Vreeland supplied.

The following are listed in chronological order.

A. J. Gordon

This Baptist Minister, founder of Gordon Bible Institute (now known as Gordon College and Gordon–Conwell Theological Seminary), and a favoured speaker working with D. L. Moody had an emphasis on divine healing. Unfortunately, he died five years before the first Pentecostal outpouring. He earlier wrote a popular book, The Ministry of Healing: Miracles of Cure in All Ages, which captured the Pentecostal mind. His views on the continuance of miracles, along with his veneration of Edward Irving as a champion for his cause, demonstrates a passing down of the Irvingite legacy into the American religious psyche.

“Edward Irving is another illustrious confessor bearing witness to the doctrine we are defending. A man of wonderful endowments, his highest gift seems to have been that of faith. He believed, with the whole strength and intensity of his nature, everything which he found written in the Scriptures. Cast upon times of great spiritual deadness he longed to see Christendom mightily revived, and he conceived that this could only be effected by stirring up the Church to recover her forfeited endowments. “To restore is to revive,” was emphatically his motto. He gave great offence by his utterances and had his name cast out as evil. He was accused of offering strange fire upon the altar of his Church, because he thought to relight the fire of Pentecost. . .” 14

“And we believe that when the Master shall come to recompense his servants, this one will attain a high reward and receive of the Lord double for the broken heart with which he went down to the grave.

Irving wrote upon this subject with his usual masterly ability. Considering the Church to be “the Body of Christ,” and the endowment of the Church to be “the fulness of him that filleth in all,” he held that the Church ought to exhibit in every age something of that miraculous power which belongs to the head.”15

Gordon’s esteem of Irving is a gesture that the Irvingites were a symbol of continuationism. The Irvingites broke the vanguard of cessationism and allowed the Protestant world of Christianity to be reborn. Such an event was required for the formation of the Pentecostal movement, but it does not show evidence of the Irvingite movement having a profound influence on structure, doctrine, or practice.

A. B. Simpson

A. B. Simpson, the founder of the Christian Missionary Alliance, and the Missionary Training Institute, (now Nyack College) gave a lukewarm response. He and his church pre-dated the Pentecostal movement only by a few years, but his influence of early Pentecostalism was important. He felt that Edward Irving had brought the gifts into central focus “but through the exaggeration of this gift and the strong temptation to use it sensationally, it became a source of much confusion and even ridicule, and a work that had in it undoubted elements of truth and power was discredited and hindered.”16

John Alexander Dowie

John Alexander Dowie was a controversial American showman, evangelist, faith-healer, and large-scale entrepreneur in faith related activities. His influence on the soon but yet-to-arrive Pentecostal movement was critical.

Vreeland recognized the Irvingite influence on Dowie and how it influenced his ministry.

During his ministry he published a weekly newsletter, the Leaves of Healing. This was his primary source of communication with the thousands of supporters he had around the world. In volume XV, Dowie calls Irving his “predecessor” and in reference to Irving states, “a greater and mightier man of God never stood upon the earth.” While there is no documentation at this point, it is conceivable that Dowie became familiar with Irving while studying for the ministry in the late 1860s. He may have read either The Collected Writings of Edward Irving published in 1865 or Mrs. Oliphant’s The Life of Edward Irving published in 1862. Dowie was admittedly influenced by Irving’s faith and anti-cessationist theology.17

Dowie was born in Scotland and moved away while a teenager. He returned and studied at the University of Edinburgh—a region and school that had positive sympathies for Edward Irving.

Agnes Ozman, the student of Charles Parham who is attributed as the first tongues speaker of the Pentecostal movement, also had a connection with Dowie. Before going to Topeka, Kansas, she went to Dowie’s Zion city, where Dowie prayed for her and she was freed from an illness.18

Charles Parham was also influenced by Dowie’s doctrines. His visitation with Dowie is noted as one of the precursors before the outpouring that allegedly happened in his Topeka, Kansas, school.19

D. William Faupel compared the structure of Dowie and the Irvingite movements and found five critical parallels.20

| Dowie and Irving Parallels | |

|---|---|

| Dowie | Irving |

| A Forerunner | A Forerunner |

| Named the Catholic Apostolic Church | Dowie renames his movement The Christian Catholic Apostolic Church21 |

| The Nine-Fold Gifts of the Spirit (I Corinthians 12) | The Nine-Fold Gifts of the Spirit (I Corinthians 12) |

| *Understood themselves in terms of the Elijah Ministry | *Understood themselves in terms of the Elijah Ministry |

| *A vital role for the ‘Ministry of the Seventy’, the Restoration Host. | *A vital role for the ‘Ministry of the Seventy’, the Restoration Host. |

A forerunner relates to the idea that these groups sought the restoration of the church in preparation for the return of Christ. * Faupel notes the importance of the last two points, though it is not evident what they exactly mean. These two are left unexplained.

Charles Parham

Charles Parham was one of the undisputed founders of the Pentecostal Movement in the early 1900s. The revival of the gift of tongues parallels the Irvingite explosion so closely, with one, maybe two exceptions, that it is impossible to be accidental.

Before getting into the details, some background about Parham and the Irvingite influece is required. First of all, his reverence for Edward Irving.

We have found that the early Catholic Fathers upon reaching the coast of Japan spoke in the native tongue; that the Irvingites, a sect that arose under the teachings of Irving, a Scotchman, during the last century, received not only the eight recorded gifts of I Cor. 12, but also speaking in other tongues, which the Holy Ghost reserved as the evidence of His oncoming.22

Secondly, Parham had to struggle with the Irvingite legacy within his own organization. Followers consisting of a faction from a former holiness group called the Brunner mission23 sought to reorganize the Apostolic Faith movement according to the Irvingite structure. Even though there is no evidence of Parham arguing for or against this conflict, he never incorporated the Irvingite leadership structure. The two parties split ways over this.

Perhaps, this is an overstatement. The analysis is from a quote found in a 1901 newsletter called The Gospel of the Kingdom. This newsletter appears to have some affiliation with the Apostolic Faith movement.

When a faction of the Brunner mission, (formerly a holiness band) undertook to organize the “movement” (After the Irvingites—Catholic Apostolics–(See Chamber’s Encyclopedia Vol IV, page 649.) turning against Mr. Parham, after receiving the truths and blessings God sent to them through him, saying he ought to go to hell for teaching such a doctrine. . .24

The specific doctrine that the Brunner mission people told Parham to go to hell is not clear.

The following is a table listing the similarities between the Irvingintes and Parham.

| Irving vs. Parham Phenomena | |

|---|---|

| Irving | Parham |

| It started with an unmarried woman | It started with an unmarried woman |

| Mary Campbell wrote in tongues25 | Agnes Ozman wrote in tongues26 |

| Mary Campbell spoke in the language of a group of Islands in the Southern Pacific Ocean27 | Agnes Ozman spoke in Chinese.28 |

| Mary Campbell’s experience was redefined as unknown tongues29 | Agnes Ozman’s later recollection is not clear 30 |

| Irving alleged never to have spoken in tongues.31 | Parham miraculously spoke in Swedish.32 |

The question of Agnes Ozman’s speaking in tongues is a controversial conclusion given here and anyone familiar with the subject may disagree. Ozman and especially Parham were highly assertive that she miraculously spoke in a foreign language. Ozman appears to become more ambiguous in time while Parham was steadfast to the original position.

Regardless of Ozman’s definition, the parallels are so close that Parham can be cited as an Irving copycat. He was attempting to recreate a similar framework and experience in an American context.

Conclusion

Scholars are correct that there is no direct data, but the indirect data and parallels are overwhelming in connecting the two parties. Parham especially attempted to recreate the Irvingite experience. Pentecostals, too, would hold that their event was directly inspired by God and deny any close connection. To admit any antecedent would suggest a type of invalid inspiration or copycat syndrome. In reality, there were too many points of similarities to state it was accidental.

- a Discipleship Pastor at Word of Life Church in St. Joseph Missouri who has his M.Div. from Oral Roberts University and D.Min. from Asbury Theological Seminary. He describes himself an emerging charismatic. He embraces the doctrines but rejects the subculture attached to it.

- Derek Vreeland. Edward Irving: Preacher, Prophet and Charismatic Theologian as found at the authoritative website, The Pneuma Review: Journal of Ministry Resources and Theology for Pentecostal and Charismatic Ministries & Leaders. Accessed April 5, 2020.

- See Gordon C. Strachan. The Pentecostal Theology of Edward Irving. London: Darton, Longman & Todd. 1973. Pg. 19

- “An interesting and so far unsolved question is the place of Edward Irving in Pentecostal theology.”— Walter J. Hollenweger. Pentecostalism: Origins and Developments Worldwide. Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers, Inc. 1997 (reprint 2005). Pg. 223. “Among such unknown sources of revival would be, for example, the Latvian Lutherans who emigrated to America on the basis of a prophecy, and the Catholic Apostolic Christians who are scattered among a number of churches in America.”—Walter J. Hollenweger. The Pentecostals. Translated by R. A. Wilson. Minneapolis: Augsburg Publishing House. 1972 (Originally published in 1969). Pg. 4

- D. William Faupel. The Everlasting Gospel: The Significance of Eschatology in the Development of Pentecostal Thought. As found in “Journal of Pentecostal Theology Supplement Series, 10.” NL: Sheffield Academic Press. 2009 (Originally published 1996). Pg. 133

- Larry Christenson, “Pentecostalism’s Forgotten Forerunner,” Aspects of Pentecostal-Charismatic Origins, Vinson Synan, ed., (Plainfield, NJ: Logos International, 1975). Pg. 25.

- Rev. Heide Baker. Pentecostal Experience: Towards a Reconstructive Theology of Glossolalia. A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the School of Humanities in candidacy for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Theology and Religious Studies. London: Kings College—University of London. 1995. Pg. 33

- Based on my research of early Pentecostal literature. See the Pentecostal Section of the Gift of Tongues Project for more information.

- The Latter Rain Evangel. March, 1917. Vol. 9. No. 6. Pg. 11

- T. B. Barratt. In the Last Days of the Latter Rain. London: Elim Publishing Company, Ltd., 1928 (Original edition first published in 1909). No page numbers in this document

- See A History of Glossolalia: Origins for more information.

- IBID. T. B. Barratt. In the Last Days of the Latter Rain. No page numbers in this document

- It is apparent from the text that surrounds this comment that his idea of Christian tongues was still in a formative stage. He struggles at defining it, and somewhat settles on both angelic or human language, depending on the context.

- A. J. Gordon. The Ministry of Healing: Miracles of Cure in All Ages. New York: The Christian Alliance Publishing Co. 1888. Pg. 102

- A. J. Gordon. The Ministry of Healing: Miracles of Cure in All Ages. New York: The Christian Alliance Publishing Co. 1888. Pg. 104–105

- The Worship and Fellowship of the Church: Weekly Sermon — By Rev. A. B. As found in: Christian Alliance and Missionary Weekly. Wednesday, February 9, 1898. Vol. XX. No. 6. Pg. 126. New York: The Christian Alliance Pub. Co.

- Derek Vreeland. Edward Irving: Preacher, Prophet and Charismatic Theologian as found at the authoritative website, The Pneuma Review: Journal of Ministry Resources and Theology for Pentecostal and Charismatic Ministries & Leaders. Accessed April 5, 2020. Vreeland footnotes this section

- The Faithful Standard August, 1922. Pg. 6

- Allan Anderson states, “In January 1900 he met emissaries from Frank Sandford’s Shiloh, and Sandford himself came to Topeka in June that year. Parham was so impressed that he decided to accompany Sandford to Shiloh and enrol in his Bible school, and he accepted Sandford’s views including his Anglo-Israelism and the possibility of foreign tongues given by the Spirit to facilitate world evangelization. En route he visited Dowie’s Zion City and Simpson’s Bible and Missionary Training Institute, among others.” An Introduction to Pentecostalism: Global Charismatic Christianity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2004. Pg. 33-34

- D. William Faupel. The Everlasting Gospel: The Significance of Eschatology in the Development of Pentecostal Thought. As found in “Journal of Pentecostal Theology Supplement Series, 10.” NL: Sheffield Academic Press. 2009 (Originally published 1996). Pg. 134

- For the original naming schemes see, Rolvix Harlan’s 1906 dissertation, John Alexander Dowie and the Christian Catholic Apostolic Church in Zion. University of Chicago. Pg. 1ff

- Charles F. Parham. A Voice Crying in the Wilderness. NL: NP. 1910. Pg. 29

- A history and background of this group cannot be located.

- The Gospel of the Kingdom. The newsletter is not completely available and lacks the front cover and its publication details. It is noted by the Consortium of Pentecostal Archives as 1901. Pg. 14.

- Thomas Erskine. Letters of Thomas Erskine of Linlathen. Edinburgh: David Douglas. 1884. Pg. 132

- See my article Pentecostal Tongues: Part 3 which has a sample of Ozman’s writing.

- Robert Herbert Story. Memoir of the Life of the Rev. Robert Story. Cambridge: Macmillan and Co. 1862. Pg. 205. See also Margaret T. Oliphant. The Life of Edward Irving, Minister of the National Church, London: Hurst and Blackett, Publishers. 1862. Vol. II Pg. 206

- Mrs. Charles Fox. The Life of Charles Parham: Founder of the Apostolic Faith Movement. Fourth Edition. Baxter Springs: NP. 1930 (republished 2000) Pg. 52

- Edward Irving changed his interpretation. See my article The Irvingites and the Gift of Tongues

- Parham would continue to assert a foreign language. Her own recollection found in the August, 1922, newsletter called The Faithful Standard Pg. 6ff does not state any foreign language. It is ambiguous.

- There is no evidence that documents him speaking in tongues. He always referenced a third party performing this act.

- Mrs. Charles Fox. The Life of Charles Parham: Founder of the Apostolic Faith Movement. Fourth Edition. Baxter Springs: NP. 1930 (republished 2000) Pg. 54

I have to say the final conclusion that Parham was trying to recreate the Irvingite experience is certainly false. The argument put forth here is a good example of the fallacy of the undistributed middle in which points in common are referenced while points of difference are ignored. Parham had likely experienced tongues at the Shiloh commune under Frank Sanford’s ministry. Additionally, Parham believed tongues to be xenolalia, and continued to insist upon that for many years even after the Topeka outpouring. If Parham was indeed influenced by Irving, he would have understood tongues to be glossolalia and would not have been so insistent upon xenolalia.