A look at the historic family name of Jesus, Panthera, and the modern debate that surrounds it.

The modern exploration of the historical Jesus has had its moments. The results are mixed: the tortured image in the movie The Passion of Christ, the sexually angst Messiah in the controversial Last Temptation of Christ, the married Jesus portrayed in the ABC television special, Jesus, Mary and Davinci, and the illegitimate son of a foreign soldier in the film Jesus of Montreal.

The last name of Jesus is an important factor in many of these conclusions. These results place the name into the realm of uncertainty that requires clarification.

People universally believe that Jesus Christ is His first and last name. However, Christ is an honorific title assigned to Him. It is not His last name. The Gospels often described Him as Jesus of Nazareth.1 Nazareth is a nickname, not the last name. Other Bible references define Him as Jesus son of Joseph or of Mary. Either one of these are correct but not a last name. External ancient texts provide a surname, Panthera.

Jesus Panthera and its variations was not a big deal within ecclesiastical or Talmudic literature, but has become a big one with some modern writers and researchers.

The first known use, and variations of the name

There are variations of the Pantherus name; Panterus, Pandira, and Panthera. The transitions between Greek, Latin, Hebrew, English, and ancient author spellings are responsible for these slight changes. The following contains detailed information.

Origen, a pious and revered second-century Christian first served the name of Panthera (Πανθήρα) in any Christian writing. The title of the work is Against Celsus.2

Origen lived in the third century. He is considered one of the most comprehensive writers of the earlier Church. The name Panthera is part of a debate between himself and an author named Celsus. We do not know much about Celsus today, except for what Origen describes. We know from Origen that Celsus was not a Christian and wrote a polemic against Christianity. He must have been popular because Origen devoted considerable time writing a treaty against his assaults.

Another important church reference is found in a writer called Epiphanius. He lived in the fourth century, residing in Salamis, Cyprus. His accounts often are strong, arrogant, and vicious against certain personalities and ideas, but contain historical value. One Epiphanius manuscript posits this name as Panther.3 While a later citation of Epiphanius has it as Pantheros (Πάνθερος) which the Latin parallel translation renders as Pantherus.4

There are two Aramaic forms; the first one is Pandira or Pandera from פנדירא, and the second is either transliterated as Panthera or Pantera from פנטירא. Pandira פנדירא is more commonly found. פנטירא Pantera occurs far less frequently.

For the purpose of this study, we will use the most commonly used English equivalent, Panthera.

How do we know His last name was Panthera?

Origen, John of Damascus, Epiphanius and controversially some small snippets from Jewish literature freely use this last name in connection with Jesus. The Church fathers do not dispute such usage, whereas there is controversy within the Jewish literary traditions. The following is a closer look at how this last name was introduced in the ancient works, how it has evolved in usage, and the contemporary debates surrounding the surname.

Origen on the last name of Jesus.

Celsus was contesting the divinity of Christ, while Origen was supporting it. The last name was not incredulous to Origen, just the way it was being used.

Celsus argued that Jesus was the result of an adulterous relationship Mary had with a soldier named Panthera.

The original manuscript of Celsus does not independently exist today, except the excerpts found in Origen’s text. In it, he quoted Celsus about Jesus;

But let us now return to where the Jew is introduced, speaking of the mother of Jesus, and saying that “when she was pregnant she was turned out of doors by the carpenter to whom she had been betrothed, as having been guilty of adultery, and that she bore a child to a certain soldier named Panthera;” and let us see whether those who have blindly concocted these fables about the adultery of the Virgin with Panthera, and her rejection by the carpenter, did not invent these stories to overturn His miraculous conception by the Holy Ghost: for they could have falsified the history in a different manner, on account of its extremely miraculous character, and not have admitted, as it were against their will, that Jesus was born of no ordinary human marriage. It was to be expected, indeed, that those who would not believe the miraculous birth of Jesus would invent some falsehood. And their not doing this in a credible manner, but (their) preserving the fact that it was not by Joseph that the Virgin conceived Jesus, rendered the falsehood very palpable to those who can understand and detect such inventions.5

Epiphanius on Panthera.

But there is another clue. It is found in work called Against Heresies.6 The citation can also be found in a seventh-century work by Anastasios of Sinai called Questions and Answers.7

οὗτος μὲν γὰρ ὁ Ἰωσὴφ ἀδελφὸς γίνεται τοῦ Κλωπᾶ, ἦν δὲ υἱὸς τοῦ Ἰακώβ, ἐπίκλην δὲ Πάνθηρ καλουμένου· ἀμφότεροι οὗτοι ἀπὸ τοῦ Πάνθηρος ἐπίκλην γεννῶνται.

For thus, on the one hand, Joseph was the brother of Cleophas, while on the other he was the son of Jacob, of whom additionally was called by the surname Panther. So that these two were born from the one surnamed Panthera.8

In other words, Joseph’s father, Jacob, was granted this surname by some unknown vested authority. The reason behind the selection of the name probably rests on economic and cultural forces. Joseph was a carpenter — a trade potentially passed down by his father. In order to conduct business and be involved in community affairs, the Panthera surname would provide a significant economic advantage. Gedaliah Alon, a historian, specializing in the Second Jewish commonwealth, believed this was an era where Jews had little or no civic rights whatsoever in Palestine and to know the Greek language and culture provided a serious economic advantage.9 “Jews who lived or traded in the urban areas had to familiarize themselves with Greek, and to acquire at least some knowledge of things Hellenic.”10

One could argue that the introduction of Panthera into his work was added much later by an editor or redactor after Epiphanius’ death. This could be true, but given that the name is used by Origen already, this is probably not the case.

John of Damascus on Panther and Barpanther.

The eighth-century Church leader, John of Damascus, also recognized the Panthera lineage. He believed Mary to be a tribal relative of Panther. “Panther begat Barpanther, so called. This Barpanther begat Joachim: Joachim begat the holy Mother of God.”11 However the Barpanther lineage doctrine is not found in the Origen or Epiphanius texts. It is likely a later tradition.

The last name of Jesus in Jewish literature.

There are potential references to Jesus in the Talmud, but this is highly controversial.

The first problem is censorship. Jewish literature has historically been under antisemitic and theological pressure from the Church. This tension has paralleled Jewish existence for almost two millennia. Because of this, references to Jesus in Jewish literature have been blotted out, censored, removed, or written in cryptic terms. However, many supposed references removed have been restored.12 Even if one counts all the restored accounts, it does not amount to very much.

The scant references that can be casually associated with Jesus and Christianity are highly debated. Jesus and Christianity in the Talmud is a study to itself. The focus here is solely on the name Panthera and how it fits in with the Jesus narrative.

Many claims are made with little reference to the source works themselves. This investigation includes the Jewish source texts. These include the original Aramaic text along with an English translation. Those readers not familiar with Aramaic are free to jump the originals and concentrate on the English.

The Targumic Dictionary.

Marcus Jastrow’s popular Targumic Dictionary seems to have the definitive answer. It refers to Jesus as “the son of Pandera”13 – a very obscure comment on first observation if there is no information available from any other source.

However this is a surface answer. The details make this assertion a difficult one to substantiate. Maybe it is referring to Jesus, maybe not.

Tosefta Hullin 2 is the closest to being a legitimate reference.

Gil Student’s popular website article on the subject, The Jesus Narrative In The Talmud, thinks Tosefta Hullin 2 is the only legitimate reference from ancient Jewish literature outside the Bible. The so-called Christian Hebraist, R. Trevor Herford, who is oft-quoted but little is known about this author, believed there were more. He demonstrates this in his book, Christianity in Talmud and Midrash.

The actual Tosefta Hullin passage:

Jacob Neusner translates it as:

Tosefta-tractate Hullin 2:23

Eleazar b. Damah was

bitten by a snake.

And Jacob of Kefar Sama came to

heal him in the name of Jesus son of Pantera

And R. Ishmael did not allow him [to accept the healing].

He said to him,

“You are not permtted [to accept healing from him], Ben Dama.”

He said to him,

“I shall bring you proof that he may heal me.”

But he did not have time to bring the [promised] proof before he dropped dead.Tosefta-tractate Hullin 2:23

Said R. Ishmael,

“Happy are you, Ben Dama.

For you have expired in peace,

but you did not break down the hedge erected by sages

“For whoever breaks down the hedge erected by the sages

eventually suffers punishment,

as it is said,

“He who breaks down a hedge is bitten by a snake (Qoh. 10:8).”14

It may have been better to have only included the line concerning son of Pantera, but the whole reference is so interesting, I couldn’t leave out the rest.

If you are curious about the actual text, here it is. If you cannot read this language, feel free to skip, as this will not affect the full explanation.15

הלכה כב

מַעֲשֶׂה בְרַבִּי אֶלְעָזָר בֶּן דָּמָה,

שֶׁנְּשָׁכוֹ נָחָשׁ,

וּבָא יַעֲקֹב אִישׁ כְּפַר סַמָּא

לְרַפֹּאתוֹ מִשּׁוּם יֵשׁוּעַ בֶּן פַּנְטֵרָא

וְלֹא הִנִּיחוֹ רַבִּי יִשְׁמָעֵאל.

אָמְרוּ לוֹ:

“אֵי אַתָּה רַשַּׁי, בֶּן דָּמָה!”

אָמַר לוֹ:

“אֲנִי אָבִיא לָךְ רְאָיָה שֶׁיְּרַפְּאֶנּוּ!”

וְלֹא הִסְפִּיק לְהָבִיא רְאָיָה, עַד שֶׁמֵּת.

הלכה כג

אָמַר רַבִּי יִשְׁמָעֵאל:

“אַשְׁרֵיךָ בֶּן דָּמָה!

שֶׁיָּצָאתָ בְשָׁלוֹם,

וְלֹא פָרַצְתָּ גְּדֵרָן שֶׁלַּחֲכָמִים!”

שֶׁכָּל הַפּוֹרֵץ גְּדֵרָן שֶׁלַּחֲכָמִים,

לַסּוֹף פֻּרְעָנוּת בָּא עָלָיו,

שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר: (קֹהֶלֶת י,ח)

“וּפֹרֵץ גָּדֵר יִשְּׁכֶנּוּ נָחָשׁ.”

Talmud Babli Sandhedrin 67a.

This passage begins the difficult journey into comparative Talmudic texts. The commonly used Aramaic version of Talmud Babli Sanhedrin 67a has no reference to Panthera in its main copy, though it is noted as an addition.16

Here is the text:

And this they did to Ben Stada in Lydda ([H]), and they hung him on the eve of Passover. Ben Stada was Ben Padira. R. Hisda said: ‘The husband was Stada, the paramour Pandira. But was nor the husband Pappos b. Judah? — His mother’s name was Stada. But his mother was Miriam, a dresser of woman’s hair? ([H] megaddela neshayia): — As they say in Pumbaditha, This woman has turned away ([H]) from her husband.17

Older manuscripts contain this complete verse, while newer ones do not. There is no reference to Stada or Pandira at all in the newer Talmud manuscripts. This has stirred controversy on many levels.

On the historical connection to Jesus, Gil Student describes three problems:

1. Mary Magdalene was not Jesus’ mother. Neither was Mary a hairdresser.

2. Jesus’ step-father was Joseph. Ben Stada’s step-father was Pappos Ben Yehudah.

3. Pappos Ben Yehudah is a known figure from other places in Talmudic literature. . . He died in the year 134. If Pappos Ben Yehudah was a contemporary of Rabbi Akiva’s, he must have been born well after Jesus’ death and certainly could not be his father.”18

There are a number of play-on-words in the Aramaic. It feels like a tongue-in-cheek reference.

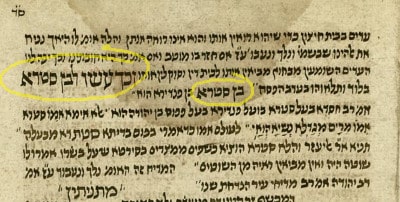

This passage gets more mysterious when one looks at the calligraphy variation found in the Talmud Babli manuscript identified with Jerusalem, Yad Harav Herzo. The picture below shows something odd:19

As circled in yellow, וכן עשו לבן סטדא בלוד “And this they did to Ben Stada in Lydda,” is highlighted in a much in a larger and bolder style – more than any other text on the whole page. It is even larger than the headers for the titles Mishna and Gemara found on the page. The name Ben Stada is written a second time later on and is emphatic, but not so large as the first time. Why? What is the scribe trying to communicate by doing this? I really don’t know, but the scribe wanted to make sure that the reader captured the nuance of this text. The emphatic calligraphy wanted to alert the reader to something not normative. Whatever the intention was, it is not clear.

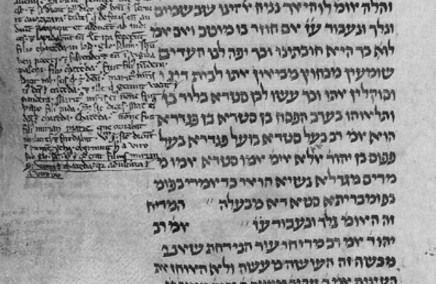

Another manuscript digitally available at the Hebrew University website, named Firenze, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale has the Panthera text as well.20

However, you have to look hard to find this one. There is nothing unusual. It is a regular part of the text. The Latin marginalia needs to be examined. It may relate to the text in question. However, the resolution supplied by the University is too low to read it.

Various interpretations of Panthera.

Celsus’ testimony was received in a limited fashion until 1859 when the argument got some welcome assistance from an archaeological discovery in Germany. A grave of a Roman soldier named, Tib(erius) Iul(ius) Abdes Pantera, was uncovered. The tombstone had information that led to a connection with the ancient Lebanese city of Sidon–a place not far from Israel’s borders and which Jesus had visited.21

The date on the grave indicated the soldier lived around the same time as Christ walked on earth. Consequently, some connected the dots and believed the Panthera on the tomb may have been Christ’s birth father.

The actual text reads:

Tib(erius) Iul(ius) Abdes Pantera

Sidonia ann(orum) LXII

stipen(diorum) XXXX miles exs(ignifer?)

coh(orte) I sagittariorum

h(ic) s(itus) e(st)Tiberius Iulius Abdes Pantera

from Sidon, aged 62 years

served 40 years, former standard bearer(?)

of the first cohort of archers

lies here22

The concept that Jesus was the son of a soldier was reintroduced to contemporary thinkers by the famed novel writer James Joyce in Ulysses (1922) though it is only very brief, it may have been shocking for the large Christian community.23 The concept of Panteras may have been the intellectual fancy during this period as Hitler used this to believe that the historical Jesus was not of Jewish origin, but “the son of one Panthera, a Greek soldier in the Roman army.”24 In 1966, Marcello Craveri’s book, La vita di Gesù, connected the Roman soldier buried in Germany, Abdes Pantera, as being the father of Jesus.25

Scholars throughout the centuries have been puzzled by Jesus having the surname Panthera and have sought various methods to explain it. Some thought Panthera to be a mockery by the Jewish writers with the emphasis on its Aramaic root meaning “spots of a leopard,” an allusion to Jesus being a deceiver. Others have concluded that it sounded similar to the Greek word for virgin and must be understood this way.

Much ado about nothing.

The last name from a religious perspective is nothing shocking or revolutionary to the Church Fathers and the Jewish texts. None of the references deny the association of the Panthera name with the family of Christ. However, the mystery behind the name is the source of the controversy. A select few have used it for historical name-calling and a few, but notable people have taken it further to mean that Jesus was an illegitimate child. It is difficult to assert this conclusion with a small handful of sentences and maybe 200 words – even more incredulous to make a connection of the life of Christ with a random tombstone found in Germany. This connection has as much a chance of being real as the James Ossuary — a funerary container with the dead bones of a person with the alleged inscription, “James, son of Joseph, brother of Jesus” written on it and later concluded as a forgery.

The Panthera connection was known by the ancients and accepted without dispute. The subject is not significant in the big scheme of things as some are trying to make it out to be.

- Luke 4:34, 18:37, 24:19; John 1:45, 18:5, 18:7, 19:19

- Origen Against Celsus. 1:32

- ΠΑΝΑΡΙΟΣ ΕΙΤ’ ΟΥΝ ΚΙΒΩΤΙΟΣ νη

- see the Latin translation of St. Anastasii, Questiones, MPG: Vol. 89. Col. 811

- Origen. Against Celsus. Book 1 Chapter XXXII. Christian Classics Ethereal Library. http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/anf04.vi.ix.i.xxxiii.html

- ΠΑΝΑΡΙΟΣ ΕΙΤ’ ΟΥΝ ΚΙΒΩΤΙΟΣ νη Or see MPG: Vol.42. VII [103] Col. 707ff

- St. Anastasii, Questiones, MPG: Vol. 89. Col. 811

- translation mine

- Gedaliah Alon. The Jews in their Land in the Talmudic Age. Transl. and edited by Gershon Levi. Jerusalem: The Magnes Press. 1980. Pg. 136

- IBID, Alon Pg. 138

- S. D. F. Salmond trans. Nicene and Post Nicene Fathers, Series II, Vol. IX. 1898: Book IV:XIV http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf209.iii.iv.iv.xiv.html?highlight=panther#highlight

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jesus_in_the_Talmud

- Marcus Jastrow. Sefer Melim of the Targumim, the Talmud Babli and Yerushalmi… New York: The Judaica Press. 1985. Pg. 599

- How Not to Study Judaism: Examples and Counter-Examples Pg. 72

- http://he.wikisource.org

- סנהדרין סז א

- http://www.come-and-hear.com/sanhedrin/sanhedrin_67.html

- The Jesus Narrative In The Talmud

- YHH Talmud Babli Sanhedrin 67a

- BNC Talmud Babli Sanhedrin 67a

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tiberius_Iulius_Abdes_Pantera

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tiberius_Iulius_Abdes_Pantera

- James Joyce. Ulysses. ND. Plain Label Books. Pg. 882 http://books.google.com/books?id=mBNjq2PSbgAC&printsec=frontcover&dq=ulysses#PPA1,M1 James Joyce. Finnegan’s Wake.

- Konrad Heiden. Der Fuehrer: Hitler’s Rise to Power. Trans. by Ralph Manheim. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. 1944. Pg. 632

- IBID http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tiberius_Iulius_Abdes_Pantera

It is curious that Jesus and his family and colleagues have no surnames in the gospels. It is also curious that the name Jesus has survived in scriptures from the fifth century when his real name was Yeshua (anglicized) and Joshua (English). When the Bible was translated into English by commission of James 1 of England, published in 1611, we should have been reading Joshua.

You raise an interesting point that the name of Jesus should be transliterated from the original Hebrew. The shift goes much further back in time than the publishing of the King James Bible to the original writings of the Greek New Testament. The writers unanimously transliterated the Hebrew for Yeshua/Yehoshua (ישוע/יהושע) as Iesous (Ἰησοῦς), which the Latin then transformed the Greek into Iesus, and the English translators adapted the Latin as Jesus.

What is the meaning of Abdes? Servant of ——– ?

I don’t have an answer to that question. If you do find one, be sure to let me know.

My own research suggests: Servant of Isis (Diessmann & Stewart); or Servant of Eshmun (a birthplace baby-name); or Servant of Jesus/Isho (Old Persian).