Practical advice for students of Biblical Greek on reading the Greek Church Fathers.

Translating the Church fathers from the original Greek is a rewarding adventure. Biblical Greek and classical students can easily adapt with some effort and new resources.

—–

Table of Contents:

- What is Patristic Greek?

- Respecting the Ancient Church Writers

- Literary Styles of the Ancient Christian Writers

- Where to Find actual Greek Texts

- Mastering the Perseus Online Greek Dictionary

- Other Online Greek Dictionary Options

- Utilizing Old Print Greek Dictionaries in Limited PDF format

- Using the Google Search Engine and Google Books with the Greek Church Fathers

- Some Other Sites Worth Noting

- Leveraging the Parallel Latin for Error Checking Your Translation

- A Good Grammar on Attic Greek

- Look out for the Infinitive

- Where to Begin

- The Secondary Role of the Translator

- Links

—–

What is Patristic Greek?

There is no such thing as Patristic Greek. The writers used the Greek that was popular in their immediate community at that time.

By the time the New Testament was written, the old Greek languages had virtually merged into one mega-language called Attic. Attic had many sub-dialects similar to the state of the English language today. Alexandrian Greek, often called Koine Greek, on which the New Testament is based on, was one of those sub-dialects. Greek Church writings are full of a number of different sub-dialects that aren’t a major challenge, but the translator has to be prepared for these slight shifts.

Gregory Nazianzus and the Cappodocian fathers preferred to use language and structure close to that of classical Greek. Origen, John Chrysostom, and the Alexandrian writers tended to use a more eastern style. Some used the subjunctive, while others did not, and adhered to the more primitive style of using the infinitive construct.

Respecting the Ancient Church Writers

It is important that the researcher approach the writings with respect. These writers were smart for their time. Many worked within multiple disciplines from theology, math, linguistics, philosophy, astronomy, technical writing, poetry, to political rhetoric and more. It is well worth to study, translate and read.

This conclusion is contrary to most modern religious minds. Many Evangelicals have been taught that the ancient writers were full of frivolity, such as debating topics about how many angels can dance on the head of a pin, or the sages possessed such rigid doctrine that it was separate from any reality or facts. For example the idea that the Church enforced the idea the earth was flat. Another tradition argues that the writers were so full of superstition that it is hard to find any rational truth. These assumptions have left many students with the idea that Patristic writings are not worth the effort.

This attitude will quickly vanish when you begin to read and translate. The Greek Fathers were close to, if not, the best within their subject of interest during that time period.

Literary Styles of the Ancient Christian Writers

What is the quality of Church literature? Some Church writers are so gifted in the Greek language that their text appears to be an art form. For example, Cyril of Alexandria has one of the most engaging styles. He was a master of vocabulary. His thoughts, word usage and grammar are very sophisticated. He stands out as one of the premier Christian writers from a literary and style standpoint. The ability to read in the original Greek is required to appreciate this, because most of the literary flow and beauty is lost in the translation.

Literary standards vary. Others like Epiphanius would fail the literary scale and appear more like a trash writer. His strong and derogatory word usage throw a translator for some difficulty.

Then there were authors like Origen who was one of the most comprehensive writers of the early Christian era. He was a genius of combining Hebrew imagery, Biblical know-how, Greek Philosophy and religious devotion into a prolific writing style.

Last of all many like Gregory Nazianzus, and many more wrote Biblical truths structured by a Greek philosophical framework.

This is likely the one place where the traditional New Testament translator will have the most difficulty. The translator cannot assume Church writers follow the same literary style and argumentation represented in the Holy Books. Rather, one will discover the majority were influenced by classical Greek writers and thought — some even quoting Aristotle, Plato, and more by name. Many Christian leaders from the second through fifth centuries emerged from Greek rhetorical arts before they became Christians. Their literature reflects either a reaction or assertion to this influence. This is a really important genre for the translator to master or at least appreciate. More on this topic can be read here: Patrology and Greek Philosophy.

Where to Find the Actual Greek Texts

Before one begins translating, acquisition of the Patristic writer in the original Greek has to be located. The easiest place to start is with Migne Patrologia Graeca—a compendium of Church fathers printed from Clement (first century) to the Council of Florence in 1438-39.

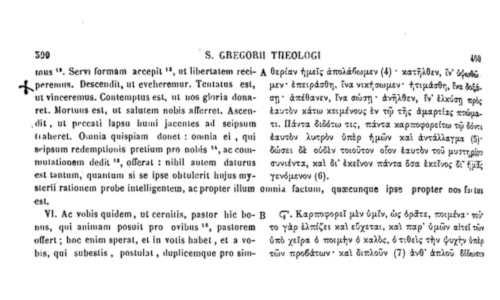

Example 1: Typical Greek-Latin page. This is a sample from Gregory of Nazianzus (Sometimes referred to as Gregory the Theologian) “In Sanctum Pascha”. Migne Patrologia Graeca. Vol. 35. Col. 400

The reproduction quality of Migne’s works are subpar and all researchers have to work around this. The problem is typical of all Migne Patrologia Graeca reprints and images.

The best site that has an outline of the books and authors of this compendium is found at Wikipedia.

The original editor of this compendium, J.P. Migne was a controversial and interesting character. Anthony Grafton of the New Republic described him as a priest-entrepreneur who “put the most questionable of business practices in the service of his devotion to Catholicism.” An entertaining and good biography of him is published by R. Howard Bloch, God’s Plagiarist: Being an Account of the Fabulous Industry and Irregular Commerce of the Abbe Migne.

There are a number of ways to access a copy of Migne Patrologia Graeca.

-

The website, Patrologia Graeca has a large list of all the volumes of MPG available for free on the internet.

-

Alternatively, Roger Pearse’s weblog also has a similar list.

-

Another alternative is to go directly to Google Books, www.books.google.com. In the Google Books search engine type, “Patrologiae cursus completus”, and a large number of this series will come up. There are two problems with Google’s Patrologia that one must overcome. First, approximately 75 of the over 161 volumes are available in full-view. Secondly, Google has randomly ordered the available volumes and it is difficult to collate or understand which volume is which.

A problem encountered with the Google Books method is quality. Some pages have been poorly scanned. A gloved thumb, finger and the palm of the worker who did the scanning are infrequently found blocking some pages from full view.

-

Or one can download the whole compendium through a P2P network using the eMule Software. The Ellopos website will guide one on how to find the files and download. It is a large file transfer and requires high-speed internet. The advantage of going through Ellopos is that the downloaded files come with an html header that provides some page navigation.

-

A good solution is to purchase digital photographic reproduction DVDs through a reseller. For example Reltech has it available for a decent price. It also includes a digitized table of contents.

-

Or go to a university library. Many have it either in book format or microfiche.

A totally digitized, searchable text version is not presently available.

MPG did not always use the best manuscripts for its work and there are some rare typos in the copy, but it is the most popularly accessible compendium in existence. If a modern translator is at a controversial point of translation, one should go outside MPG, seeking a better or comparable manuscript for confirmation.

Times are rapidly changing and one shouldn’t stop with Migne. It is a good starting point, but there are now more options. Many Museums and institutions are digitizing their manuscripts and making them available on the internet. This type of availability was unheard of even ten years ago. This era provides one of the greatest opportunities to study Ecclesiastical literature in the history of this genre.

Finding the text is a start, but there are going to be many words you do not know, or have never seen before. Understanding and utilizing ancient Greek dictionaries is a must. The following section should help.

Another good option, and perhaps the best one is to use TLG: The Thesaurus Linguae Graecae–a product of the University of California, Irvine. It is a huge database and well respected among academics. The best part is that all the documents are digitized, the interface is excellent and the search engine is fast and thorough. However, it requires payment to exploit its full power. You should be able to access it through your local university. The drawbacks are that there is no Latin parallel translation that you can sometimes cheat when the Greek appears difficult and sometimes the MPG editors comments have some value.

Mastering the Perseus Online Greek Dictionary

For those new to Perseus, it digitally provides an older version of the Liddell and Scott Greek Dictionary, and a number of other smaller but widely accepted dictionaries as its database. It is the most extensive and useful site by far on the net for this purpose.

It is a must-have tool in the Patristic translators’ toolbox, and it is free.

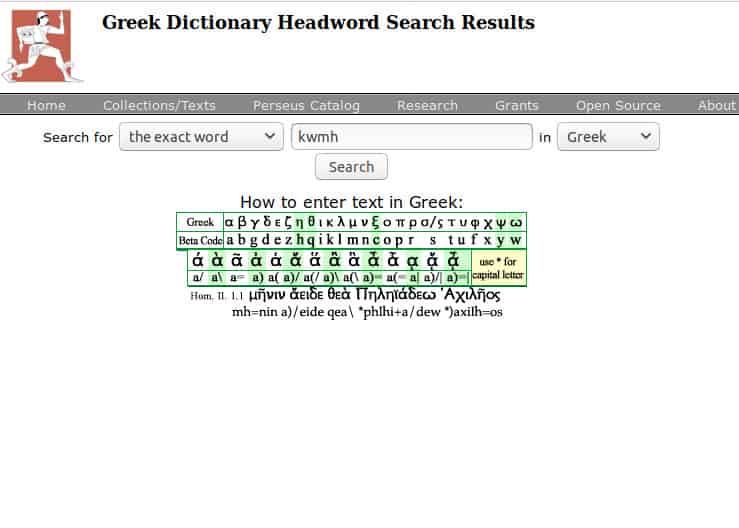

Example 2: Entering data into the Perseus search engine

Be sure to use “w” for omega ω, and “h” for eta η. For example the Greek word κώμη “unwalled village”, one must enter it as kwmh, not kome.

There are a number of human errors that the Perseus program does not try to help. The first one is not typing in the correct transliterated characters. The transliterated characters are displayed on a graph below displaying its search box on the web page. If one mistypes “o” instead of “w”, which happens often in trying to represent the omega in Greek, there may be no results. The second error is simply to mistype the actual search query and Perseus responds that it cannot find the term. This can happen often. It is good to check typing accuracy. If the search comes up negative, retype and try again.

Other Online Greek Dictionary Options

If the above methods do not work, one can delve even further.

Other online places available are:

- The University of Chicago’s Logeion website. It rivals Perseus in capability but has one major virtue that Perseus does not presently have–you can type Greek directly into the search button rather than a transliteration.

- Harvard’s Archimedes Project. It has similar but much less refined search capabilities as Perseus, and TLG

- The modern Greek website called Komvos. This one has not been tested but may offer some good resources.

- Dictionnare Grec Ancien – Français. It is a Greek-French dictionary that has brief definitions, usually six words or less. The layout is cumbersome and could use a really good search engine. It is nevertheless handy in certain situations.

- Lexigram is a modern Greek website that does a thorough job on parsing Greek verbs and nouns. It also provides a link to Perseus for definitions.

Utilizing Old Print Greek Dictionaries in Limited PDF file format

Still, these online dictionaries may not be enough. A list of ancient Greek dictionaries in pdf format can be found in this document: Ancient Digitized Greek Dictionaries,

The above link is the location for many helpful dictionaries. After you use them for a while, a pattern will be seen. All the dictionaries are typically drawing from a similar source, and that is from the great multi-volume work, Stephanus’ Θησαυρος της Ελληνικης Γλωσσης. It is the closest to a definitive source for Patristic Greek. However, it has some caveats.

-

First of all, it is a Greek-Latin dictionary. It has never transitioned to a Greek-English one. Therefore, knowledge of Latin is mandatory. However, it is worth the time to learn.

-

Secondly, it is not available as a digital text. It is found in pdf image format that does not allow for text searching. It forces the user to visually go page-by-page to find the desired result. The multi-volume series is very large, and consists of nine volumes, this means searching for a word takes considerable time.

-

The structure of Stephanus’ text is somewhat puzzling. The version that is available at my download site is a modified version done almost three centuries later that tried to rectify this situation, but there are still some oddities. These are more inconveniences than actual barriers.

Outside of the net, there is a popular publication that many use — Lampe’s Patristic Lexicon. This is an addendum to Liddell and Scott’s Greek Dictionary. This dictionary is not legally digitally available, way overpriced, and has about a 30% success rate of finding the word you are looking for. It is available at most local university and Bible college libraries.

When Lampe provides a good answer, it is worth it. For example the word ἀγέλη. Perseus renders it as a “flock of animals” whereas Lampe defines it as “flock of Christ”, which, in Church translations, makes a huge difference.

The standard dictionary used for translating the Greek New Testament, A Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament and other early Christian literature, is not exhaustive enough for ecclesiastical Greek. The success rate of finding the word here is not good.

Using the Google Search Engine and Google Books with the Greek Church Fathers

Searching for a problematic Greek word over the internet using your browser’s search engine can be very helpful. Simple queries in English, Greek or the combination of the two can sometimes lead to some very good results.

If you use Google’s search engine for example, sometimes Google may produce too many results. A good way to limit the search is to add a descriptor to the Google search. For example if one types in the word άρμοττει in the Google search bar for the word found in Theodore of Cyrene’s Graecarum Affect. Curatio (MPG. Vol. 83. Col. 818), it produces quite a number of results that do not initially appear helpful. If one enters “άρμοττει perseus”, or “άρμοττει greek”, or “άρμοττει bible” or similar as the search string, it will reduce the results to something very workable.

Google will also search through a number of good Greek Bible websites along with a number of old Greek dictionaries. This is where Google Books can be very helpful. Google search will scan all the Greek dictionaries it has in its database, even exotic ones such as Lexicon Thucydidæum: a dictionary, in Greek and English, of the words, phrases, and principal idioms, contained in the history of the Peloponniesian war of Thucydides printed in 1824.

A very helpful method, albeit largely unknown, is the use of inputting Greek text into Google Books search engine. Google Books has somehow made their scans of ancient Greek books searchable text. Input Greek type into the search query bar provided with the Google book interface. It will search for the word, and if it exists it will find it in specific documents. It is a great aide in finding problem words. It isn’t always consistent and the results may vary. Certain characters like the letter χ do not work in queries at all.

Another important note on typing in the Greek characters in the Google Books search; it appears to work only with unaccented Greek.

Important — if you are using the Google search engine, and find results quoting Ecclesiastical writings cited in the original Greek, be careful. It has been observed a number of times that the Greek texts in Google’s Book program have been passed through a character recognition program and offered by Google as actual digital texts. It is approximately 80% accurate. Some of the output is random, other parts are not even close. These quotes should never be used in any form of research.

Example 3-4: Searching within a Google Book using Greek type. τετρανωμἐνων as found in Origen’s Catena on Corinthians. τετρανωμενων and τετρανωμενος did not render any results but τετρανωμενον revealed usage in a Basil writing:

Clicking on the Basil document reveals a Greek text with a Latin parallel translation:

The Latin provides the first real clue into the meaning of the word.

On a rare occasion the only way to find an ancient meaning is through its usage in modern Greek. Google search results will also provide the use of modern Greek words in Greek blogs, newspapers and other contemporary mediums. Google offers mechanical translations into English of many Greek based internet sites. Comparing between the original Greek site and the mechanical Google translation can sometimes offer clues. But one has to be careful as it is not always accurate.

The internet has greatly improved in facilitating the use foreign and ancient fonts. Typing in the Greek word, with or without accents, into the Google search bar can bring some good, and surprising results.

Some Other Sites Worth Noting

A site for comparative Biblical textual work is http://unbound.biola.edu/. This is handy for comparing Biblical passages with Patristic Biblical citations and quickly identify similarities and differences.

A Greek-based website found at http://www.ellopos.net/elpenor/greek-texts/septuagint/default.asp is also valuable. If you type directly in Greek using the search engine on the top of Elpenor’s homepage, it will give a multitude of results from Plato to Migne; often giving clues where an existing English translation can be found.

Leveraging the Parallel Latin for Error Checking Your Translation

That is, of course, the parallel Latin exists, which in Migne Patrologia’ case is around 98%.

One of the best approaches to translating the Greek writers requires knowledge of Latin. Most Greek texts have a later Latin parallel text written next to it. This is not always accurate, but it is one of the best helps. This also is a major aid in understanding Greek verbs and participles where multiple conjugations can be attributed to the same form. It can also help identifying the case of nouns, word order, and choosing the right English for a Greek word with a wide semantic range.

On a very rare occasion, when an English equivalent for a Greek word cannot be found at all, then one has to exclusively rely on the Latin. For example in Theophylacti Bulgariae’s Expositionis in Acta Textus Alter (MPG. Vol. 135. Col. 864). A portion described the event of the division of tongues in the book of Genesis and he used the imperfect middle/passive, 3rd person singular verb διενέμετο (dienemeto). Any type of attempt with Perseus and Google come up negative. The only option left is the Latin, which used divisa est—a perfect passive “was divided.” It fits in nicely here.

On most occasions the Latin translator remains in a static translation mode — even abandoning proper Latin syntax in order to be consistent with the Greek. One has to be always cautious as a Latin translator can easily drift into dynamic mode. This will also vary between translators. The translator of Epiphanius tended to be more dynamic than Cyril of Alexandria’s. This is often a good thing to find happening, as the translator is elucidating on a Greek text and giving his own interpretation. In general, the Latin translations are done at a later date, and one can glean a different point of view based from their period.

It can be argued the Latin is the best method of error controlling your Greek translation. Many of the Church fathers have never been translated into English, nor or some verbs and nouns available in any Greek dictionary. This sometimes can be your only source of comparison.

A Good Grammar on Attic Greek

Although there are many grammar books on Attic Greek, there are few good contemporary ones. The only up-to-date book is Donald J. Mastronarde’s Introduction to Attic Greek. It is a great book for those new to Attic, but it is not a final grammar. There have been reviews that this book is too complicated, but for those with experience in Biblical Greek, it is very useful. Many of the pitfalls that the Bible translator would fall for, Mastronarde clearly addresses. One must keep in mind that the grammars for the New Testament are still helpful for 90% of the translation work.

Look out for the Infinitive

The uses of the infinitive and separately the subjunctive with many of the Greek writers vary. The infinitive, especially in older Greek manuscripts, has a wide range of usage and is not always straightforward. It cannot be assumed to always mean “to…”, but has a number of meanings. It can also act as a gerund or even a subjunctive. One needs to be ever mindful of this. For more detailed information on this go to, The Various Uses of the Infinitive in Ancient Greek.

Where to Begin?

When one first begins to experiment and delve into the Patristic world, Irenaeous, Bishop of Lyon’s writing, Adversus Haereses (MPG. Vol. 7), may be the best one to begin with. There is a parallel English translation one can easily make reference to at http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/anf01.toc.html.

In approaching the task of translating any ancient Church writer, it is important to understand the author’s background. The best initial place to go is New Advent’s website. It contains the most comprehensive background of Church leaders anywhere. Also Wikipedia will give you a brief outline as well.

The Secondary Role of the Translator.

The researcher, translator, and/or reader of any piece of Church literature must be cognizant of the fact that most ancient Church writings available today have a twofold interpretation process; the written and oral traditions.

The written is easier to identify than the oral. Since the oral tradition has been lost for centuries, it is the role of the researcher/translator to reconstruct this. More on this can be found in the following article, The Written and Oral Traditions of Church Literature.

Links.

- Migne Patrologia Graeca

- Online Access: Google Books

enter “Patrologiae cursus completus” in the search tool - P2P network using eMule or equivalent: Elpenor’s Link to Migne’s Works

- Purchase from Reltech

- Outline of the Books and authors: Wikipedia

- Dictionaries

- Perseus

- Ancient Digitized Greek Dictionaries and Ancient Greek Dictionaries for Download.

- Lampe’s Patristic Lexicon (not available digitally)

GWH Lampe, A Patristic Greek Lexicon (Oxford: Clarendon, 1961) - Grammars

- Donald J. Mastronarde. Introduction to Attic Greek. Berkeley:

University of California Press. 1993 (not available digitally) - Resources

- New Testament Morphology

- Biola’s Engine for Comparing Greek Bible Manuscripts

- Greek Bible

- Septuagint

- The Thesaurus Linguae Graecae (TLG)

- Author backgrounds and biographies:

New Advent, Wikipedia - Pangiotes K. Chrestou. Greek Orthodox Patrology: An Introduction to the Study of the Church Fathers. Translated and Edited by George Dion Dragas. New Haven. Orthodox Research Institute. 2005

- Syntax

If this article has helped you in your journey in translating Patristic Greek, or have some other valuable tips not listed here, please leave a comment.

Great blog! I’m one of those “took biblical Greek and am trying to work on Gregory of Nazianzus but am over my head” kind of guy, and have found Albert Rijksbaron’s book “The Syntax and Semantics of the Verb in Classical Greek: An Introduction” (3rd edition) to be very helpful (especially with that pesky infinitive!).

And another implementation of the Liddell, Scott, Jones Ancient Greek Lexicon you can find here, easy to search, just type in Greek or Latin characters. http://lsj.translatum.gr/wiki/Main_Page