A 3000-year general history on the Book of Psalms numbering and divisional systems.

The structural development of the Book of Psalms has an interesting and complex history.

The results are the examination of documents spanning a 3000 year time period. The reader will be journeying through Hebrew, Greek, Syriac, Latin and English texts. Don’t worry. You don’t need to know the languages itself to join in this expedition. This work is designed for both the researcher and the passionate lay reader. Many pictures will be provided that will assist. One can marvel at the beauty of the handwritten text without understanding it.

The findings show that the Psalms began as an unordered list with no assigned numbers. The arrival of the Greek translation called the Septuagint brought about a numbering scheme for the Book of Psalms.

The Septuagint contains 151 Psalms, though this was not adhered to by other traditions which went up to 155. Verses were not introduced until much later. Verses were covered in a previous article titled, A History of Chapters and Verses in the Hebrew Bible.

As demonstrated by the Dead Sea Scrolls, the order of the poems in the Book of Psalms was not established in the early centuries. This happened after the widespread acceptance of the Septuagint later on.

The Septuagint assignments of numbers and order were assumed by the Latin translators, which in turn had an influence on the English Bible tradition.

The headers introducing most of the Psalms are the most controversial and misunderstood. In regards to the headers only, we are not so sure today on the meaning behind the original Hebrew or even the Greek translation. This has led to a multitude of interpretations even within the English Bible translation tradition.

These are mere generalities and the readers of this blog prefer details and substantiation. The following is how the above conclusions were arrived at.

How this conclusion was arrived at

The focus was on comparing the Hebrew, Syriac, Greek, and Latin manuscripts for building a framework.

The Book of Psalms is a large compilation and to examine the details of each and every Psalm would be a major ambition. So this project has been reductionistic to save time and resources. Psalms 9 and 10 as found in the English Bibles serves as the basis for this study, and more general information is provided for the rest. There are two caveats though, no Dead Sea Scroll text has been found that contains Psalms 9 and 10. We have to simply live with that and work with other manuscripts that are available. Secondly, the references to the Psalms in the Talmudic writings have been ignored because of the time involved.

This collection was originally written in Hebrew, but the greatest influence of the divisions, numbering and the modern English name of this Book can be found in the Greek edition called the Septuagint. This Greek translation is old—the first one appeared around 250 BC.1 Greek was the universal language of government, the courts, and trade in the middle east from 200 BC to 300 AD. It was critical to learn Greek for both commercial and financial success. Greek held prominence similar to English in the international community today. The Septuagint was the authoritative text for Jews who lived in Egypt and the Roman Empire. The available manuscripts for this Greek translation outdates almost every Hebrew Bible text except for the Dead Sea Scrolls.

The prominence of the Book of Psalms in the narrative of human history

The Book of Psalms, whose poems were first collated around 970 BC, is one of the oldest collections of poetry/hymns on the human record. Sure, there are older ones such as Ludlul-Bel-Nimeqi — an Akkadian narrative developed around 1700 BC with themes similar to that of the Book of Job.2 Or Homer’s work The Iliad which has entertained children and adults for almost 2700 years. Neither of these works reflects the depth of the human soul on the themes of joy, loss, deceit, war, peace, love, yearnings, awe, the divine interplay between God and man, and mysteries of life that the Book of Psalms invokes in the hearts of readers.

The power of human emotion somehow transcends from the original Hebrew into almost every known language of the world. The Book of Psalms demonstrates that great poetry has a magic unto itself that overcomes language and cultural barriers.

Authors of the Book of Psalms

The main contributor to the Book of Psalms was King David (1010–970 BC). Out of the 151 Psalms in the Christian Bible today, 73 are traditionally understood to be produced by him. The rest were produced by various Israelite authors: even one accredited to the great leader Moses.3

How the Book of Psalms received its English name

The Hebrew name for the Book of Psalms is תהילים, Tehillim, which means praises.

The Greek translators translated this collection of poems as ψαλμοί Psalmoi which then was adapted by the Latin translators as Liber Psalmorum and then anglicized as the Book of Psalms in all the English Bible versions.

The order of the Book of Psalms in the various Bibles throughout history

The ancient Hebrew editors squeezed the Book of Psalms in between II Chronicles and the Book of Job in their third section of writings called the Ketubim (Writings). This is the place for tertiary writings. They had less authoritative power than the writings of Moses (the Torah) or the section allotted to the Nevi’im (The major prophets of ancient Israel. The minor prophets were relegated to Ketubim). 4 The Jewish people call the collection of the Torah, Nevi’im, and Ketubim the Tanakh.

The Septuagint has a different classification system. The Greek editors broke the format into three categories that were different from the Hebrew structure. The first one was the Pentateuch (The anglicized Greek word for the five books of Moses). The second was poetic and wisdom literature which included the Book of Psalms. It is sandwiched between Job and Proverbs. The third was the histories of Israel which went from Joshua to III Maccabees. The last category was the prophets. Both major and minor prophets were lumped into this section.

The Latin Vulgate agrees with the Septuagint ordering system. This framework was adopted by the later English Bible translators.

The internal structure of the Book of Psalms

A Dead Sea Scroll called the Great Psalm Scroll which was copied around 30 – 50 AD has a substantial amount of Psalms, but not all. However, given by what is found in this scroll, the order and number of Psalms are different than what is found in the present English Bible traditions. The different order may be a distinctive of the Qumran community that copied the Psalms, or, could be that the order within the Psalms had not been settled by this period.

The English Book of Psalms traditionally contains 151 psalms. This was not always the case in history. There has been up to 155.5 A good explanation for these differences can be found by a Dead Scroll specialist named Peter W. Flint in his article Psalm 151 and the Dead Sea Scrolls.

What are the extra Psalms 151b – 155? Here is a composition of these texts. Psalms 151-155 translated by W. Wright, 1886

The method to demonstrate the start and end of a Psalm

The Great Psalm Scroll

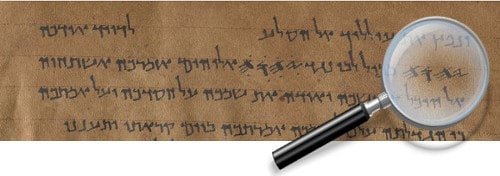

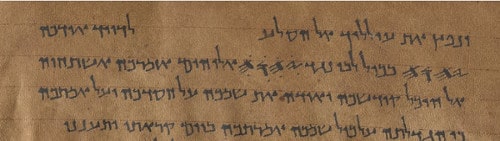

The Great Psalm Scroll identified the beginning of a poem by spacing and often a small attribution to the author. They did not use numbers to divide the Psalms. This device came later.

One of the distinctives of the Great Psalm Scroll was the reverence for the holy name of God (the tetragammeton). The copyists believed it unholy to alter the original calligraphic script for the personal name of God and so the left it in the much older Hebrew writing style:

The Greek texts

These ancient christian manuscripts which contained the Book of Psalms were examined: Codex Vaticanus 1209 (@315AD),6 Codex Sinaiticus (@345 AD),7 and Codex Alexandrinus (@420 AD).8

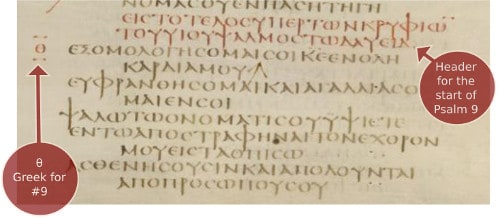

Both the Vaticanus and Sinaiticus has each Psalm numbered. The Sinaiticus goes a step further and colors the header text in red. The Codex Alexandrinus has all the Psalms numbered but the headers are not so easy to distinguish. The physical condition of Codex Alexandrinus is lower than the two mentioned above. Codex Alexandrinus lacks the aesthetic beauty of its two other counterparts.

All of them emphasize the chorus line called a dipsalma (a pause between two verses so that different parts of the choir could properly harmonize in singing the Psalm).

It is clear that the numbering system in use with the Psalms today comes from the Septuagint but it is unclear when the Greeks started this tradition. We know it began before the 300s because both the Codex Vaticanus and Sinaiticus contains them. However, none of the New Testament writings contain any numbered Bible references. Similarly, the Jewish Aramaic community does not cite such a tradition either throughout the Mishnah or Gemarrah – the two main pieces that constitute the Jewish Babylonian Talmud.

The Latin

Two Latin texts examined from the 900s: Codex Toletanus,9 and Theodolphianus,10 have no numbers assigned to any poem.

The Syriac

Three Syriac texts were looked at, though I will not make comments about two them on the issue of numbering and order. They are the product of collations from the 1800s provided by Western-based scholars. These texts show modern influences in reference to structure. The first text is the UBS Syriac Bible, 1979. This Bible can be traced to the Arabic scholar, Samuel Lee, in the early 1800s. The Second one is the Urmia edition which also traces its roots to the 1800s.

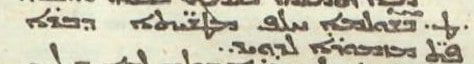

There are only a handful of ancient Syriac Old Testament manuscripts available. One manuscript, the @750 AD Codex Syro-Hexaplaris Ambrosianus11 is the only one available online and so we will have to settle for this one. The text has the Book of Psalms marked by a Syriac number. There is also Latin numbering and verses on the outside of text, but this is likely a later addition.

The Leningrad Codex

Next to the Dead Sea Scrolls, this is one of the earliest complete Hebrew copies of the Tanakh available. It was completed in 1008 AD by the hand of Samuel ben Jacob in Cairo, Egypt.

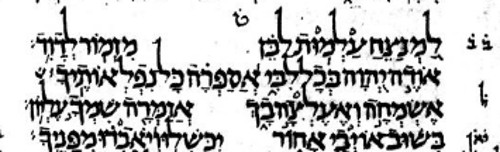

This Codex, unlike the Great Psalm Dead Sea Scroll, has a Hebrew number assigned to each poem. This Codex follows the numerical pattern already established by the Septuagint with a few exceptions.

When the Hebrew numbering system was added to the Masoretic texts is not known. Historians generally believe this became entrenched by Rabbi Solomon ben Ismael around 1330 AD. This is much later than the publication of the Leningrad Codex.12

Latin Texts

Codex Tolentanus (950 AD)13 and Codex Theodolphianus (950 AD)14 do not have any numbering system for the Book of Psalms. This may have been for artistic reasons that the numbers were excluded. More has to be researched on the Latin texts to see if numbering was consistenly omitted from the Book of Psalms.

The problem of Psalms 9 and 10. Were they intended to be separate or different poems?

There is a difficulty between the Septuagint and the Masoretic texts like the Leningrad Codex on the numbering of Psalms 9, 10, and 11. The Hebrew Leningrad Codex breaks Psalm 9 into two poems while the Septuagint does not. At least from what can be seen from the Latin Codex Theodolphianus (@950 AD), the medieval Catholic Church followed the Septuagint structure.15 The modern English Bibles follow the Septuagint structure via Latin influence.

The Hebrew stops at 9:21, and begins a new poem at 9:22, while the Greek continues it as the same poem.

It has been contended that Psalm 9 and 10 poem is an acrostic. It apparently uses each letter of the alphabet in a unique order until the end of the poem. It cannot easily be seen and I have my doubts as there are 7 missing letters from this poem.16

The Septuagint may be correct on this one. There is no header in the Hebrew that defines a start of a new poem at 9:21. There is a musical interlude called the sela in Hebrew, and translated as a dipsalma in Greek at this point. The poem is one entity. It should not have been separated into two because of the sela.

The Headers

Most poems listed in the Book of Psalms has a traditional header as a preface to them. One will frequently see at the start of a poem: by David, For the director of music, song of ascents, A contemplation of Asaph etc. On other occasions it can be a lengthy explanation of the Psalm such as Psalm 9 “For the director of music. To the tune of “The Death of the Son.” A Psalm of David.”17.

These were not penned as part of the poem by the original author but added later by an editor. This must have done early because there is no ancient manuscript without them.

The Psalm 9 header has an inconsistent history and translations are highly variable. It is an interesting facet in the Book of Psalms. This problem applies with more headers in the Book of Psalms but these potential instances have hardly been investigated for this article.

The muth-labben

The greatest reason for this variety is the original Hebrew. The Hebrew introduces Psalm 9 with: לַמְנַצֵּחַ, עַל-מוּת לַבֵּן. Lamnazecha, a’l-muth labben. The problem here is we don’t know what this line, especially מוּת לַבֵּן muth labben means. There is no definitive dictionary or historical artifact that can enlighten the translator. Because of this, translators throughout the centuries have arrived at different conclusions.

If one is to take מוּת לַבֵּן muth labben literally here, it could be understood as death to a son. However, this is not the theme of the Psalm itself which starts with an emphatic note of thankfulness. Muth labben is more likely an idiom related to a musical rite or instrument, but this is a calculated guess.

The New International Version Bible translation translates the header as:

For the director of music. To the tune of “The Death of the Son.” A psalm of David.18

The NIV is ignoring the Greek altogether and translating literally from the Hebrew. The concept of music is in the right direction, but “death of a son” doesn’t fit.

The English Standard Version (ESV) takes a more cautious approach and does not even attempt to translate מוּת לַבֵּן muth labben:

To the choirmaster: according to Muth-labben. A Psalm of David.19

Given the ambiguity of the idiom, the ESV translation is the proper approach.

The Greek

This line was translated as: εἰς τὸ τέλος ὑπὲρ τῶν κρυφίων τοῦ υἱοῦ ψαλμὸς τῷ Δαυιδ eis to telos huper ton kruphion tou psalmos to Dauid. Unfortunately, the Greeks caused more problems than solutions with their translation of this difficult Hebrew passage.

Εἰς τὸ τέλος eis to telos is frequently used throughout as a header in the Psalms. This is the Greek equivalent for the לַמְנַצֵּחַ lamnazecha. No one is exactly sure what it means either in the Hebrew or the Greek. In the Greek it can be literally understood as to the end but this hardly helps in understanding its context within the Psalms.

A recently published translation of the Septuagint, titled A New English Translation of the Septuagint translates εἰς τὸ τέλος eis to telos as, Regarding completion. Others understand to the end as in the end of the world and the coming of the Messiah. The apocalyptic theme doesn’t fit with the poems but, as will be shown later, has been popular in various editions.

The second part of the header of Psalm 9 isn’t any easier to comprehend except that this is the only occurrence in the Book of Psalms, . . .ὑπὲρ τῶν κρυφίων τοῦ υἱοῦ ψαλμὸς τῷ Δαυιδ . . .huper ton kruphion tou psalmos to Dauid. A New English Translation of the Septuagint translated it as, “Over the secrets of the son. A Psalm. Pertaining to David.”

The Syriac

The Syrians took the most liberty in translating the Book of Psalms headers. This is partly due to the translators using the Septuagint as their basis. The basic premise today is that the headers were influenced by a commentary on the Psalms by Theodore Mopsuestia. Not every manuscript from the Syriac manuscripts are the same either, and it is hard to trace this back to one author. There is more variety in the Syriac headers than in the Greek or even the Latin.

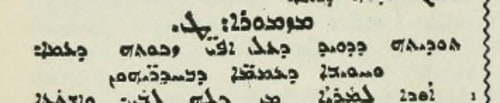

For example, Andrew Oliver translates the header on Psalm 9 from a Syriac text which is the same as the United Bible Society’s 1979 version.

A Psalm of David. — The session of the Messiah, and his reception of the kingdom, and frustration of the enemy.

This UBS Bible quotation is based on a Syriac edition collated and edited by Samuel Lee in 1826. What earlier manuscripts Mr. Lee used is not known at this time.

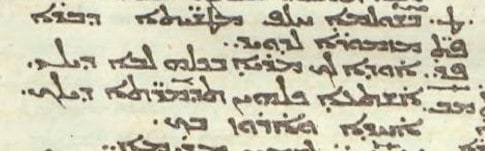

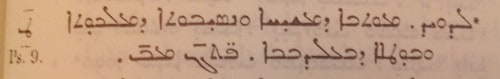

For the really inquisitive, here are pictures of the actual Syriac text he drew from:

However, this is not representative of all the Syriac texts. The Urmia edition has a completely different take.

Unfortunately, an English translation has not been properly prepared for the Urmia edition. The Urmia text was published around the same time as Samuel Lee’s edition. A superficial reading demonstrates the text is more conservative and non-messianic.

Any Syriac reader will push for the earlier documents Codes Syro-Hexaplaris Ambrosianus (@750 AD) and this one once again has a different header for Psalm 9:

The translation reads, “For completion on account of the hidden things of the son. A Psalm of David.”20 The Ambrosianus text literally follows the Greek.

The Latin

The Latin manuscripts researched for this article reflect the same inconsistencies found within the Hebrew, Greek, and Syriac texts. The difference is found in which ancient Latin Bible the manuscript adhered to.

-

The Vetus Italica— a collation of second-century Latin Biblical quotes stitched together into a cohesive narrative has: “In finem propter occulta filii, psalmus ipsis david,”21 Unto the end, for the hidden things of the Son, a Psalm by David about these things.

-

The renowned philologist for his time, Santes Pagnino, tried to correct this problem in the 1400s when he compiled Liber Psalmorum, Hebraice. He took a middle path and translated it as “Victori super Muth-labben Canticum Davidis” — For the Victor, about the Muth-labben, a Song of David.22

-

The Codex Theodolpianus (@950 AD) took from the Latin version credited to Jerome “victori super morte filii canticum david”23 For the Victor, about the death of a son, a song of David.

-

The Codex Toletanus, created around the same time as Theodolphianus, simply ignored any header at all.24

- See A Brief History of the Septuagint for more information

- see Ludlul-Bel-Nimeqi by Joshua J. Mark

- Wikipedia entry for Psalms

- see the Hebrew Bible listing at Wikipedia for more information

- Qumran Psalms Scroll

- Codex Vaticanus Online pg. 628

- Codex Sinaiticus online

- Codex Alexandrinus online image IDs, 143222 and 143223. Manuscript handwritten pages 534–535

- Codex Toletanus Pg. 356

- Codex Theodolphianus 147r

- Codex Syrohexaplaris Ambrosianus Pg. 526

- The Hebrew Bible as found at the Catholic based New Advent website.

- Codex Toletanus Pg. 356

- Codex Theodolphianus 147r

- Codex Theoldolphianus online

- Ronald Benun is an *independent community scholar* (I am unsure what that means) who proposes this interpretation.

- Psalm 9 NIV

- NIV as found at Bible Gateway

- ESV as found at Bible Gateway

- My translation

- Bibliorum Sacrorum Latinae Versiones Antiqua seu Vitus Italica D. Petri Sabatier. Book II. 1742

- Liber Psalmorum, Hebraice Joannis Konig. 1662

- Gallica. Bibliothèque nationale de France

- Codex Toletanus Pg. 356

Thanks for your story on Psalm 9 and 10. I don’t agree with some people’s take on them. I believe the headers have always been there. I get confused when I hear them say things like, they don’t know what it means or how to translate it. I once accidentally had a computer translator translate the muth labben line as “curdled milk.” I was shocked. It being a computer an just naturally doing it’s job versus thinking about it, gave me the best translation of muth labben I’d ever seen.

When using the Strong’s Concordance, it’s important to understand that one can’t really get a good original translation of those Hebrew and Greek words, unless they keep tracing back the “from….(such and such 1234)” and the looked up word’s cousins and such. We know “muth” means death, but we have to look at the words “clabbered, labbered, and such,” to see that “labben” is spoiled milk.

After I saw this, I knew right away what Psalm 9 and 10 was talking about, because there’s the scriptures saying, “You poured me out like milk, and curdled me like cheese.,” from Job 10:10. It’s pointing to how God would turn Jesus over to death, in the sense of his word being the sincere (colostrum milk) of the Lord, that Peter speaks of that we’re first weaned on, until we move on to meat. It’s like the saying, “Don’t cry over spilt milk.” Jesus was a drink offering poured out for us, that poured out himself to death.

I’ve seen horror movies before I got saved, from the werewolves Howling movies, where in human form, they’d change and melt into a puddle, and it was painful, and then they’d be reformed into the werewolves. Musically, concerning the headers in the Psalms, I know that from musical inference, musical cues, meter and idiom and such, that they are like diddys or prep for not only getting the musicians ready, but as what today we’d call something like the 20th Century Fox 20 introduction before a movie.

I’d say all of the Psalms had these, with David for his theme, whatever it was, and then, probably in the case like Psalm 9 and 10 and others, the shown header, is what I’d call a modern day second studio making the film under the upper studio umbrella. In a sense, like today how, when we see a famous director’s studio diddy be heard, or a super hero studio, or a horror one, and so on, we know what to expect. Yet, not always could one know, “Will this be one of so and so’s action, adventure, romance, mystery, or so and so pieces?”

I once sat down and did a study of one of these Psalms, Psalm 56 maybe (I can’t recall, the one that says something about the “title.” One church father wrongly said, that it was pointing to Pilate not removing the title above Jesus’ head, which was a great thought, but not what this Psalm was saying. That was from the Douy Rhymes and New Duoy Rhymes translation.).

I saw that originally, in the original Hebrew, that it’s diddy would’ve started out with something like a slow long low string sound being produced by a stick across the strings. At the same time, that as this was happening, that a mounting flute, cymbals tinkling with those triangles and metal sticks clinking, and brass sound would come to a crescendo, and in this case, with the Hebrew indicating at it’s root versus the final word that John Strong’s had good intentions in translating as “music director and such”, really meant, “times, times, and dividing of times,” and I knew that that by inference was a scripture pointing to the end times and God’s judgement.

In modern film scores, I’d kind of compare it to how Close Encounters Of The Third Kind starts out, with the same long string sound, and then arubtly changing to the brass sound, and the movie opens. The chaotic theme that happens after the diddy, I would kind of compare to the scene in Planet Of The Apes, where the main character first encounters the apes, as they chase the humans into the corn, and the ape officers have the sticks they’re holding up above that, and it’s a chaotic sound. By inference, musically I hear like minded themes used in other movies, like Superman The Movie, which I mention below, which shows me that usually other composers score the same type of scene the same way.

From there, the diddy spilled over into the Psalm, that also would’ve been likewise scored, but I stopped because someone much smarter at these things versus I, needs to finish this subject, and the Psalm shifts in gears, and turns into a chaotic nightmare about God’s wraith. People listening would’ve started out sitting down to David or such’s newest piece, like we would a rock concert I’d say more so than an orchestra today. I’d say people looked forward to new Psalms the way we today look forward to our favorite musician’s new album or single.

I’d say it would’ve been like modern fans fainting over seeing so and so come onto the stage. The priests would’ve controlled the crowd. In this case, at this point, the audience would’ve been looking for a place to hide. Eventually, the score comes back to a peaceable melody and points to how Jesus will be merciful and come looking for all those who are ready to be found. I was shocked that so much thought went into the Psalms.

I’m sure now that we all have themes, and I’m sure the great conductor Jesus wants us to see his score on our lives someday, but we need to be ready for the bad parts, where there might not be any music at all, because Jesus sat the baton down and left the room because of our sins.

As for Psalm 9 and 10, I do believe it’s an acrostic and that much more is being said with that in Spirit, as Solomon explores in Psalm 119. In my opinion from looking at musical inference, and when I say that, I mean in a sense, I mean in the sense kind of if one smells smoke, then probably near by is fire, and so if they go someplace else later, and again smell smoke, it’s probably true that if they smell smoke there, there’s also fire nearby. In a court of law, lawyers and detectives pretty much use inference to solve every crime.

In scriptures this works spiritually, in where if you see The Spirit using a certain words and phraes, where other such and such words and phrases pop up, inference says that that’s how The Spirit inspires, and so one should find almost the same thing in other cases, where the same such and such words and phrases appear, and they do. So, musically, this works the same way.

It doesn’t mean that every composer is the same, but that if you told a hundred composers to score a certain piece of film, and gave them no way to know or listen to how any of the other composers scored that particular piece, according to the musical laws of inference, even though each composer will score it differently, pretty much all of them are going to follow a basic overall umbrella sound over the smaller differences.

So, with Psalm 9 and 10, being it’s about the death of the son, it’s diddy would start out with the Messiah theme, whatever that is, and then quickly go into the mourning scene and lead to death. Yet, in the overall narrative so to speak, after listening to all the Psalms like a series of albums, where one would watch the creator shape and mold his music from genesis to thesis to masterpiece, here, you’d eventually see the Messiah theme become more and more dominating versus only teasing, and with Matthew (And, I’m not saying the gospels have themes.) so to speak, the Messiah theme would finally explode onto the screen.

Since I once loved watching Superman, I would compare the Messiah theme and the death of the son theme, to an unused track in John William’s score to Superman The Movie, right after his parents send off his capsule for earth, when Krypton starts to get ready to explode. In the theatrical release, it cuts to this happening, but originally there was a sequence where his parents are fleeing while the Krypton council has sent out an officer to arrest them.

The triumphant music of their child escaping, which I’d compare to a type of Mesiah theme, turns into mourning theme, which slowly builds up to a death theme, as the parents flee. Whenever the scenes cut back and forth with percussion and brass mounting, while we see the officer tracking them, there the brass really heightens, then cuts back to more of Krypton being destroyed, where low brass sounds are heard, and then it cuts back into the theme used in the movie, where the score descends into strings playing franticly as Krypton is about to explode, and then there’s silence. A shot of Krypton from a distance appears, and then it explodes.

As the debris scatters away and the child’s capsule comes into view heading for earth, the theme returns to strings and some brass, with a searching sound, until it gets to earth, and then you’re teased with the Superman theme again briefly, before the capsule crashes to earth, pointing to how the Superman theme will later explode in full, after Superman appears for the first time. I see Psalm 9 and 10 kind of like that, but in a much new and living way. I don’t mean at all for one to listen to Superman, but to God.

If you want to hear some good Christian movie score music, may I please suggest you check out by Mark Darby Slater, and Art Osbornes’ score for it, which he’ll send to you for free (If there’s copies still available) for a small donation. It has a rich old Hollywood sound to it like the old Bible movies had, but it’s new and original.

Jesus bless to all those in the faith.