Quick thoughts on concepts, and critical words in the translation of the I Corinthians 14:10 catena attributed to Cyril of Alexandria.

This text outlines several interesting particulars: how ancient Greek words previously used in classical Greek rituals had become Christianized, and the office of the circuit preacher, which required the knowledge of many languages. These elements are examined in more detail below.

Several words in the translation of Cyril’s catena on I Corinthians have Greek antecedents to them that require careful examination, especially as it relates to the doctrine of tongues. The results demonstrate the Alexandrians had adapted these words from its original intent to their own meaning.

Table of Contents

- Overview

- Critical Greek Words

- Conclusion about the Greek Words

Overview

The text being discussed is contained in a sequence not found in Migne Patrologia Graeca, but in Phiippus Edvardus Pusey’s, Cyrilli: Archiepiscopi Alexandrini In D. Joannis Evangelium. Pusey based his text on a copy found at the Library of Pantokratoros on Mount Athos.

Both Migne and Pusey claim the origins of their works to be from Cardinal Angelus Maius, but contain different texts. Migne’s version has fewer words than Pusey. It is also clear and concise. Pusey’s version has more text with some repetition, along with a few slight variations. It also appears that some words are missing. Reading it feels choppy.

The Greek used in Pusey’s version is old. It has Doric, Attic, and Ionic representations in them. This type of text would not be unusual for an international center that the City of Alexandria was. It was a melting pot of many Greek languages and dialects.

Pusey’s text does not contain a Latin parallel one. The Latin typically provides quick clues on how to translate problem words.

Critical Greek Words

Εἰσεφοὶτων

The first important word to note is εἰσεφοὶτων. This word is used exclusively in this text. It is found nowhere else (at least so far). A scouring of the internet, and all the major dictionaries, provided no clues. However, the root of εἰσεφοὶτων is φοιτάω, which means:

-

Perseus online: go to and fro, backwards and forwards, keep going from one part to another, roam wildly about, roam about in frenzy or ecstasy of a Bacchant; of sexual intercourse go into a man or woman; resort to a man, woman or place for any reason; As object of commerce—to come in constantly or regularly, be imported

-

Lampe’sPatristic Lexicon: spring-up, pollulate, of doctrines (Pg. 1847)

-

Donnegan’s A New Greek and English Lexicon; Principally on the plan of the Greek and German Lexicon of Schneider: to wander, roam about, come frequently, to go to school as a disciple or learner, wander about in a state of frenzy (Pg. 1348)

-

Schrevelius’ Greek Lexicon Translated into English: to frequent as a scholar, not as a master, come, go, approach, rave, be mad (Pg. 616)

-

Stephanus’ Thesaurus Graecae Linguae: This text is in Latin but all the definitions above, with perhaps the exception of Perseus, are taken from this source text. (Didot Bros. Volume 8. Pg. 989)

Perseus has defined φοιτάω from classical Greek sources. This is not surprising because Perseus uses Liddell–Scott–Jones (LSJ) Greek Dictionary as their basis. LSJ hardly reference Patristic writings in any of their dictionary definitions. However, it does show where the word originated. It described the Bacchants who roamed about in a frenzy or ecstasy, but it had other meanings as well.

Stephanus, Lampe, Donnegan, and Schrevelius recognize that φοιτάω has the quality of raving, or frenzy, but another principal attribute was that of frequently visiting or traveling to a place. It also became associated with going to school, discipleship, and learning. Lampe put a more developmental aspect to it. It was to seed doctrine within a community initially. Schrevelius specifically stated φοιτάω as a verb referring to a scholar, not a master.

There are also other words that come from the same root that give hints on how to translate εἰσεφοὶτων. Donnegan is especially descriptive of these:

-

φοὶτητήρ one who goes and comes, any place, especially a school. A disciple, learner. One who is frantic (Pg. 1349).

-

φοῖτος roaming about, the wandering of the mind, insanity, also frenzy, that of the frantic votaries of the Bacchus and Cybele (Pg. 1349).

Schrevelius, spells φοὶτητήρ as φοιτητής as one who comes frequently to a master or scholar (Pg. 616).

These definitions give greater confidence in correctly translating the I Corinthians 14:10 catena portion.

The above definitions, plus the context of the Cyril text, demonstrate that εἰσεφοὶτων is considered as a localization of φοιτάω or perhaps intensified. The εἰσεφοὶτων was a person who went into Churches to teach the doctrines. The above dictionary definitions give the appearance that it was an entry or mid-level position, educating on the doctrines of the church, but not by a Bishop or a Cardinal.

The English equivalent would be a circuit rider. The best modern equivalent was the system devised by the Methodists for clergy to serve more than one congregation at a time. In Cyril’s explanation, the emphasis was on teaching in a circuit where the churches were linguistically different, and the base requirement for this person was to be multilingual.

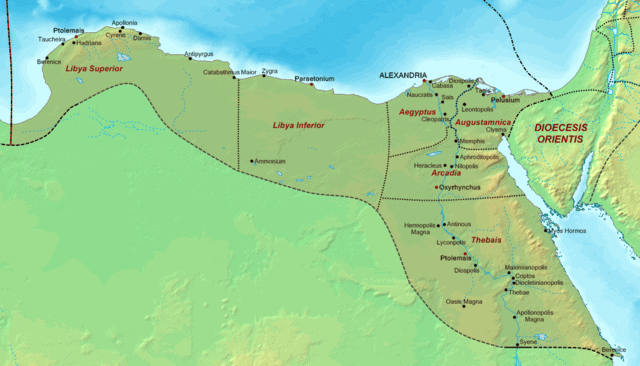

The Alexandrian church had a wide area of service and control. The Catholic-based New Advent website described their domain; “Within its jurisdiction, during its most flourishing period, were included about 108 bishops; its territory embraced the six provinces of Upper Libya, Lower Libya (or Pentapolis), the Thebaid, Egypt, Acadia (or Heptapolis), and Augustamnica.”1

The following graphic gives a good idea of the large area that Alexandria served. It is found at Wikipedia’s Diocese of Egypt webpage:

Although it does not specifically state the languages served, it can be inferred there were many.

Κεχρῆσθαι

The second term that is used to describe tongues-speaking was κεχρῆσθαι. This verb is not an exclusive term used by Cyril but one shared by Origen. This one has a wide semantic range. Perseus defines it as to furnish what is needful, to declare, pronounce, proclaim. In the passive, it is to be translated as: to be declared, proclaimed by an oracle, to consult a god or oracle, to inquire of a god. It has not changed over time. In the instance of this catena, to proclaim was used, but this may be too weak. “To prophecy,” in the traditional religious sense, would be more suited, but this word now carries some contemporary meanings that would mislead many readers. Therefore, my translation of this catena conservatively translates it as to proclaim.

Ὲρεύγεσθαι

The verb ἐρεύγεσθαι is another unique word. Its root is ἐρεύγομαι: to belch out, bellow, or roar. Hence, to loudly utter, as in a public display, or simplified, to utter, is a good English word choice.

This verb falls into the realm of the christian doctrine of tongues, especially those interested in the glossolalia aspect. It is a neutral form where one cannot argue for or against glossolalia on account of this word.

Μανθάνοντος

This present active participle masc. gen. sg form of μανθάνω was used in the Septuagint and also by Origen. One of the dictionaries defines it as: learn, especially by study but also by practice, learn by heart, acquire a habit of, and in past tenses, to be accustomed to, perceive, remark, notice, understand. Hence it is not a supernatural phenomenon, in this context of I Corinthians 14:10 people hearing a language that they have learned or is their principal language.

Conclusion about the Greek Words

The christian texts demonstrate that the standard Greek words that were used for the Bacchus Greek prophets in the past had evolved and changed into Christian definitions. The history of the word was known and understood but fell out of widespread usage.