The fourth-century Syrian St. Ephrem and the christian rite of speaking in tongues.

The legend attached to St. Ephrem asserts the Pentecostal rite was the supernatural ability to speak in a foreign language. The Corinthian reference by the real St. Ephrem was a liturgical one relating to everyday language.

There are four references on the doctrine of tongues that have particular importance found so far in his writings. Two reinforce the ancient traditions of Pentecost. All point to the perceived continuation of this mystical event, and one clarifies his understanding of Corinthian tongues.

There is a potential fifth reference found in a hymn, Nineteen Hymns on the Nativity of Christ in the Flesh: Hymn XVIII: Praise be to Him Who sent him!1 He used tongues metaphorically and gives little data on the doctrinal aspect. It is mentioned here for the very curious to look further.

Many readers are asking, who was St. Ephrem? What is Syriac and the Syrian community’s contribution to early Christianity?

Background Information

St. Ephrem, otherwise known as Ephrem the Syrian, lived in the fourth century in an area that borders today between Turkey and Syria, presently occupied by a Kurdish majority. His hometown, Nisibis (now known as Nusaybin), was on the borderline between Persian and Roman forces and faced Persian encroachment on numerous occasions. The city finally succumbed to the Persians when the Romans ceded it through negotiation. This loss forced Ephrem and all the Christians to flee to a neighboring Roman-occupied city called Edessa. Edessa was a melting pot of different varieties of the christian faith, along with pagans and philosophers.

Ephrem set out to teach and instruct the people of Edessa. One of his methods was the use of hymns. He was so good at this that one blogger suggests that his theological-poet status remained unrivaled for a thousand years until Dante.2

He also was a writer and orator. Other luminaries during his time highly praised his poetic genius and theological insight.

The Catholic Encyclopedia sums him up best:

It is certain, however, that while he lived he was very influential among the Syrian Christians of Edessa, and that his memory was revered by all, Orthodox, Monophysites, and Nestorians. They call him the “sun of the Syrians,” the “column of the Church”, the “harp of the Holy Spirit”. More extraordinary still is the homage paid by the Greeks who rarely mention Syrian writers. Among the works of St. Gregory of Nyssa (P.G., XLVI, 819) is a sermon (though not acknowledged by some) which is a real panegyric of St. Ephraem. Twenty years after the latter’s death St. Jerome mentions him as follows in his catalogue of illustrious Christians: “Ephraem, deacon of the Church of Edessa, wrote many works [opuscula] in Syriac, and became so famous that his writings are publicly read in some churches after the Sacred Scriptures. I have read in Greek a volume of his on the Holy Spirit; though it was only a translation, I recognized therein the sublime genius of the man” (Illustrious Men 115). Theodoret of Cyrus also praised his poetic genius and theological knowledge (Hist. Eccl., IV, xxvi). Sozomen pretends that Ephraem wrote 3,000,000 verses, and gives the names of some of his disciples, some of whom remained orthodox, while others fell into heresy (Church History III.16). From the Syrian and Byzantine Churches the fame of Ephraem spread among all Christians.3

Ephrem spoke Syriac, which is part of the Aramaic group of families—a family that has a connection with Hebrew. Syriac is close to the one Jesus primarily spoke while on earth. Since Syriac was neither Latin nor Greek or Hebrew, Western thought has sidelined this language in the majority of religious discussions. Awareness of Syriac literature is on the rise in today’s academic circles because it intersects with Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. It fills in critical gaps of early Christian literature.

St. Ephrem on the doctrine of tongues is one example where it slightly fills voids left in both Greek and Latin literature—nothing groundbreaking, but useful nonetheless.

Biographical References on Ephrem and Miraculous Language Acquisition

A sixth-century biography about St. Ephrem relates two instances of miraculous language acquisitions to him but also the leaders whom he encountered. The emphasis on both these accounts is on the equality of St. Ephrem and the Syriac Church with that of the Greek and Coptic Churches.

The Coptic church and especially its base in Alexandria, was the cradle of early Christianity and held significant influence. The Greeks represented the largest population of Christians throughout the ancient world. The concept of miraculous language acquisition is subsidiary to the sense of equality. In this case, we are indebted to the biographers writing about tongues even though it was not their primary objective.

These miraculous references are likely later additions to the legend of St. Ephrem. On the other hand, their idea of it being a miraculous ability to speak in a foreign language gives insight into the perception of the doctrine of tongues in the sixth-century Syrian Church.

Their concept of tongues was consistent with the majority of Greek and Latin ecclesiastical tongues texts that preceded them and remained this way for almost a thousand years after.

Here are the actual texts.

St. Ephrem’s encounter with Abba Bishoy

After he waited a little while, the blessed one went out from the society and set apart from them with his student, and went to Egypt. He hoped to reach the desert of the holy and solitary one who was in it. When he reached the city of the name Antinus, he was glad. He asked the inhabitants of the city of what direction to the desert. They ascended to the wilderness, and the holy one brought to the desert also his disciple, who was an interpreter. They reached a cave that there was a holy man of God, Abba Bishoy. The holy Bishoy did not know Syriac, and neither did the holy Ephrem know Egyptian. They asked from God and was granted to Bishoy so that he uttered words in Syrian and Ephrem, Egyptian. And Ephrem, the holy saint, was greatly affected by the appearance and conversation of the great man of God, Abba Bishoy. The Lord promised him while on the mountain of Edessa, “that your reward in the kingdom is as the great man Abba Bishoy is being rewarded.” And the blessed master Ephrem dwelled with the great man of God for a week, and they abounded in the company of each other.4

Abba Bishoy, alternately known as Pishoy or Bischvai, is a revered Egyptian desert father within the Eastern Churches, and especially within the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria.5 He lived in the fourth century.

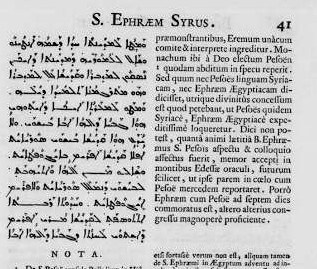

The Original Ephrem-Bishoy Text

The above was translated by me with some help from the Latin and a later German translation. One must exercise caution with the Latin as it appears wonky when compared to the original Syriac and the German. The italics reflect that these sentences neither reflect the Latin or German, and I think is closer to the original intent of the Syriac original. This translation may change. Here are the originals.

Click on the image and you will be brought to the Syriac copy along with a Latin parallel text. The portion translated starts on the bottom of Page 40 (XVI) and runs to the top of Page 42.

A German translation can be found at University of Fribourg website (Chapter ten).

St. Ephrem’s encounter with Basil

When Basil greatly pressured that he [Ephrem] was to receive the service of the priesthood, he appealed many times by the necessity. He laid a hand and made him a deacon, and then Basil laid his right hand upon him and gave the ordination of his ministry. He took his hand and, in the Syriac language, said, “Accept, O Lord, that he should stand (in your presence).” And then Ephrem, the master answered in the Greek language, “Accept me, and may I stand, O God, in your favor.” And the gift of the Greek language was given to the master Ephrem by the prayer of the true shepherd Basil, as it was the result of him asking from Him in complete humbleness. And the grace of the gift was given to the master Basil who was uttering Syriac by the prayer of the holy Ephrem. So was the laying of hands granted of the priest to the disciple.6

The Basil referred here is to Basil of Caesarea, also known as Basil the Great. He had a high standing as a Bishop in the Greek-based churches surrounding various regions of modern-day Turkey. He also is known as one of the Cappadocian fathers alongside Gregory of Nyssa and Gregory Nazianzus. Both Western and Eastern Churches recognize him as a Saint.7

Both these stories are predicated on the idea that St. Ephrem knew neither Greek nor Coptic and both Bishoy and Basil did not know Syriac. There is speculation surrounding whether St. Ephrem spoke Greek—most veer towards he did not know Greek. The global power of Greek, and the location that St. Ephrem lived, suggests that he would have at least an elementary knowledge of Greek. One would have to suppose knowledge unless evidence proves otherwise. His commentary on I Corinthians showed below suggests that he was exposed to the language: whether he spoke it, he did not state. The likelihood of him knowing Coptic at his arrival to Egypt is low, though the text later states he lived there for eight years. For that many years to pass, the assumption is that he became fluent in the Coptic language.

It is doubtful that Bishoy or Basil knew Syriac.

Determining whether this event is true or false is not essential. The vital aspect is how the people perceived the christian rite of tongues in their world. They understood this rite as the miraculous ability to speak in one or more foreign languages.

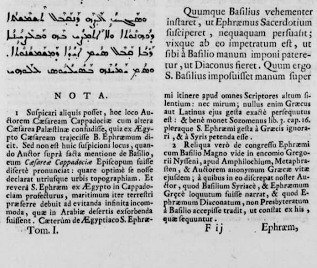

The Original Ephrem-Basil Text

Click on the image and you will be brought to the Syriac copy along with a Latin parallel text. The portion translated starts on Page 43 (XIX) and finishes on 44.

A German translation can be found at University of Fribourg website (Chapter fourteen).

Ephrem on I Corinthians 14

Ephrem wrote numerous commentaries on the books of the Bible. I Corinthians was one of them. The only existent text available today is an Armenian version which is not available online. Even if an online version exists, I cannot translate this language. A Latin translation is easily available, though it doesn’t read easily. This problem may relate to the fact that it is a translation of a translation.

His reflections on the Corinthians tongues passages are, for the most part, not unique. Two references stand out.

I Corinthians 14:13

Therefore, the one who speaks in a language, let the person pray, that this person of the Greeks may be interpreted through the authority of the Greek language because he is speaking in a foreign language. For the gifts of the Spirit were in accordance with this course, because kinds of languages were given to one, and another interpretation of languages, and the one requires the work of another. Namely, that person who was speaking was on behalf of him who was being interpreted: moreover, the Church is both entities. 8

Here is the original Latin:

Qui ergo loquitur lingua, oret, ut per graecam linguam Graecorum possit interpretari illud, quod loquitur lingua aliena. Dona enim Spiritus hoc tenore erant, quia uni data erant genera linguarum, et alteri interpretatio linguarum, ut unus opus haberet alterius; ille scilicet qui loquebatur ejus qui interpretabur; Ecclesia autem utriusque.9

This is a difficult passage to either translate (The Latin is not a clean work) or analyze. More background knowledge is required to understand his rendering. Fortunately, a European traveler to Israel in the fourth century named Egeria documented that Greek was the language of instruction in the indigenous Syrian assemblies while another priest stood nearby immediately, translating into Syriac.10

With this evidence in mind, St. Ephrem was referring to I Corinthian 14:13 in his context: speaking or reading in the foreign Greek language. A language that only a master of Greek could convert into the Syriac language.

He had no inclination of this passage referring to a sudden, miraculous event. Nor does he refer throughout the Corinthian commentary to utterances, groans, or joyful exuberances. These were outside the realm of any liturgical expressions in the Syrian community.

I Corinthians 14:22

If, therefore, languages had been given that person on account of the people, so that they knew the time of the new Gospel through the agency of language. Therefore, languages are now a sign; they are not for believers. What kind do you ask? but for unbelievers. One may see clearly with why the Jewish people had been dispersed, to those of which was written, and they do not take heed in such a way, said the Lord. Prophecy, on the other hand, is not for unbelievers, but believers: if then they do not believe what you are saying, how can they hear what you are speaking?11

Here is the Latin:

Si ergo propter populum illum datae sunt linguae, ut scirent per linguas tempus Evangelii novi, ergo linguae nunc in signum sunt non fidelibus, quales vos estis, sed infidelibus, Hebraeis videlicet divisis, illis de quibus dictum est: et nec sic exaudiant me, dicit Dominus. Prophetia autem, non infidelibus, sed fidelibus: si enim non credunt, quod dicis, quomodo audient quod loqueris?12

In this particular passage, he is not even referring to the Pauline text but the purpose of Pentecost. His description nonetheless infers Corinthian tongues as human language.

Notes

This article is part of the ongoing Gift of Tongues Project which has a fourfold goal:

- Locate source literature on the subject

- digitize the original texts

- translate into English with critical notes

- trace the perception of tongues in the church from inception until modern times.

The GOT Project started perusing the massive Migne Patrologiae Graecae, the overwhelming series called Corpus Scriptorum Christianorum Orientalium, and touching on portions of Migne Patrologia Latina. The CSCO was especially utilized looking at Syriac church literature with the hope of breaking through with St. Ephrem once his works came up.

These lofty goals were in the pre-internet era in the 1990s, and print books still reigned. The MPG and MPL volumes were available at a local university library, while CSCO was available through interlibrary loan from a university in Pittsburgh. The interlibrary loan only allowed one book at a time, and at some point, the source library began to decline requests. These factors led to a decision for the exclusion of Syriac literature from the GOT Project.

However, an email from a person named Michael Büschlen in December of 2019 changed things. He sourced original texts of St. Ephrem on tongues and forwarded these finds. Instead of the long and tedious task of locating and collating the documents, the only challenge for me was to translate the Syriac and Latin texts. All of the citations forwarded by Mr. Büschlen were of high quality. One especially shone through and validated the GOT Project analysis of I Corinthians.

St. Ephrem on tongues is in honor of Mr. Büschlen’s contribution.

- Ephrem the Syrian. (1898). Nineteen Hymns on the Nativity of Christ in the Flesh. In P. Schaff & H. Wace (Hrsg.), J. B. Morris & A. E. Johnston (Übers.), Gregory the Great (Part II), Ephraim Syrus, Aphrahat (Bd. 13, S. 260). New York: Christian Literature Company.

- https://goudenhoorn.com/2016/07/27/the-vita-of-st-ephrem-the-syrian-1/

- http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/05498a.htm

- My translation

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pishoy

- my translation

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Basil_of_Caesarea

- my translation

- St. Ephraem S. Ephræm Syri commentarii in epistolas D. Pauli nunc primum ex Armenio ex Typographia Sancti Lazari. 1893. Pg. 76

- For more information see The Language of Instruction in the Corinthian Church.

- My translation

- St. Ephraem S. Ephræm Syri commentarii in epistolas D. Pauli nunc primum ex Armenio ex Typographia Sancti Lazari. 1893. Pg. 77