How the doctrine of cessationism percolated within certain Church of England splinter groups and especially those that immigrated to America.

This is part 4 of the series of Cessationism, Miracles, and Tongues. Part 1 was an introduction with a general summary. Part 2 uncovered the medieval psyche surrounding the supernatural, miracles, and magic. This same article also contained how the protestant movement revised the perceptions of miracles in the early church from the traditional catholic opinion. Part 3 demonstrated how the Church of England, especially through the influence of the Puritans, officially formulated the doctrine of cessationism.

The most populous splinter group from the Church of England was the Methodist movement. This is where the analysis starts for Part 4.

John Wesley and the Methodists on Miracles

As previously shown in this series of articles on cessationism, the doctrine never really became a universal one in the Church of England, and neither did it become a factor in its prodigy — the evangelistic and fast-growing Methodist movement.

The Methodists were a reform group within the Church of England in the 1730s, but later became independent in 1795. This independence happened four years after the founder of the movement, John Wesley, had died. The worship and liturgy was very similar to its parent organization.1

Wesley himself gave a sermon called The More Excellent Way about the existence of miracles. He wrote that their cessation was incorrect:

It does not appear that these extraordinary gifts of the Holy Ghost were common in the church for more than two or three centuries We seldom hear of them after that fatal period when the Emperor Constantine called himself a Christian, and from a vain imagination of promoting the Christian cause thereby heaped riches, and power, and honour, upon the Christians in general; but in particular upon the Christian clergy. From this time they almost totally ceased; very few instances of the kind were found. The cause of this was not (as has been vulgarly supposed) “because there was no more occasion for them,” because all the world was become Christian. This is a miserable mistake; not a twentieth part of it was then nominally Christian. The real cause was, “the love of many,” almost of all Christians, so called, was “waxed cold.” The Christians had no more of the Spirit of Christ than the other Heathens. The Son of Man, when he came to examine his Church, could hardly “find faith upon earth.” This was the real cause why the extraordinary gifts of the Holy Ghost were no longer to be found in the Christian Church — because the Christians were turned Heathens again, and had only a dead form left.2

Wesley promoted miracles in the life of the believer. He believed the purpose of miracles were a natural outcome of any Christian with a vibrant faith.

And these signs shall follow them that believe – An eminent author sub – joins, “That believe with that very faith mentioned in the preceding verse.” (Though it is certain that a man may work miracles, and not have saving faith, Matthew 7:22-23.) “It was not one faith by which St. Paul was saved, another by which he wrought miracles. Even at this day in every believer faith has a latent miraculous power; (every effect of prayer being really miraculous;) although in many, both because of their own littleness of faith, and because the world is unworthy, that power is not exerted. Miracles, in the beginning, were helps to faith; now also they are the object of it. At Leonberg, in the memory of our fathers, a cripple that could hardly move with crutches, while the dean was preaching on this very text, was in a moment made whole.” Shall follow – The word and faith must go before. In my name – By my authority committed to them. Raising the dead is not mentioned. So our Lord performed even more than he promised.3

Wesley asserted a doctrine of the perpetuation of miracles when writing a defense against Conyers Middleton.4 Middleton wrote that miracles had ceased after the establishment of the Church. The refutation countered by piecing together historical references. However, he does not appeal to miracles in his own ministry or the world about him as part of his treatise.

Elsewhere, in his A Farther Appeal to Men and Religion, he recognized the role mysticism and its expressions but adds a cautionary note.

Are you not convinced, Sir, that you have laid to my charge things which I know not? I do not gravely tell you (as much an enthusiast as you over and over affirm me to be) that I sensibly feel (in your sense) the motions of the Holy Spirit. Much less do I make this, any more than ‘convulsions, agonies, howlings, roarings, and violent contortions of the body,’ either ‘certain signs of men’s being in a state of salvation,’ or ‘necessary in order thereunto.’ You might with equal justice and truth inform the world, and the worshipful the magistrates of Newcastle, that I make seeing the wind, or feeling the light, necessary to salvation.

Neither do I confound the extraordinary with the ordinary operations of the Spirit. And as to your last inquiry, ‘What is the best proof of our being led by the Spirit?’ I have no exception to that just and scriptural answer which you yourself have given, — ‘A thorough change and renovation of mind and heart, and the leading a new and holy life.’5

A retired methodist pastor and blogger, Craig L. Adams, deeply looked into Wesley and miracles and concluded: “Thus we can say that Wesley would not have fully endorsed either cessationism or pentecostalism. Extraordinary gifts and miracles have not necessarily ceased, but they are not necessary proofs of the Holy Spirit, either.”6

The Irvingites and Miracles

This article will stop for a moment and reiterate that the doctrine of cessationism is unique to the reformed branch of churches (Presbyterian, Baptists etc.) and does not reflect the greater traditional protestant psyche which led more to de-emphasism or in many cases continuation. However, another item besides the Methodists shall be included and that is of Edward Irving who was a cleric of the Scottish Church along with his congregation based in London, England, during the 1820s. His leadership and congregation were controversially engaged in the restoration of the gifts. Irving was well aware of two strong influences: the Scottish Church belief in the cessation of miracles and the rise of rationalism within the greater English religious community. He countered both with the restoration of miracles:

This power of miracles must either be speedily revived in the Church, or there will be a universal dominion of the mechanical philosophy; and faith will be fairly expelled, to give place to the law of cause and effect acting and ruling in the world of mind, as it doth in the world of sense. What now is preaching become, but the skill of a man to apply causes which may produce a certain known effect upon the congregation? — so much of argument, so much of morality; and all to bring the audience into a certain frame of mind, and so dismiss them well wrought upon by the preacher and well pleased with themselves.7

Irving proceeded to state:

I know nothing able to dethrone this monster from the throne of God, which it hath usurped, but the reawakening of the Church to her long-forgotten privilege of working miracles.8

The Scottish Church took exception to Irving’s unorthodox activities and was referred to the London Presbytery for review in 1832. He was not charged with reviving the supernatural rites of tongues and healing which he abundantly broke from the Scottish Church tradition. Rather, he was charged with not following procedural issues such as allowing women to speak. In doing so he was found guilty and defrocked. 9 The procedural route was chosen because of the theological controversy surrounding cessationism. There would be less of a chance of clearly settling the problem if this manner was chosen.

For more information on the Irvingites, see The Irvingites and the Gift of Tongues.

The Migration of the Church of England breakoffs to the Americas

The Puritan strand in England had run its course after the late 1600s, but its influence had moved with the migrants to the United States. The tradition of cessationism passed on with the puritan-based members of the Church of England – mainly those who settled in New England. It was also found with the Presbyterians who crossed the Atlantic from Scotland. A separation group of Puritans from the Church of England called the Pilgrims, along with the Baptists, and the Congregationalists, also carried the seeds of cessationism.

The Baptists

The reader will be stopped for a moment and to ponder on the Baptist influence. Religious persecution in England caused many christian groups calling for reform in the Church of England to immigrate to other countries. The Baptist contingent was one of them and its migration to the United States included the doctrine of cessation. One of its American proponents was Augustus Strong (1836–1921). He was a first-rate thinker and a well studied student. He worked his way up from Yale, and over the years became the President of Rochester Theological Seminary. He wrote a compelling argument on miracles which was one of the better ones from a traditional perspective. He fully understood the rationalist angle that a miracle is a suspension of natural law or a manipulation of nature. He carefully disputed that miracles were of a personal nature that happened inside the person’s mind and not an external or visible act. He provided a well worded alternative framework for a miracle being something different and more wonderful that included the supernatural. This is a good piece of literature, but he breaks the momentum with this statement:

We may not be able to mark the precise time when miracles ceased. There is reason to believe that they ceased with the first century, or at any rate with the passing away of those upon whom the apostles had laid their hands. So long as the Scripture canon was incomplete, there was need of miracles. When documentary evidence was at hand, miracles were seen no longer. The fathers of the second century speak of miracles, but they confess that they are of a class widely different from the wonders wrought in the days of the apostles.10

His great thinking was restrained to the bounds of baptist cessationist policy.

The Baptist themselves are a hard organization to follow the flow of cessationism through the centuries. The emphasis on the independence on the local congregation allows for flexibility in this area. They dropped the cessationist clause in the New Hampshire Confession of Faith in 1844. Why it was dropped is unknown. Historical practice shows they have remained structurally immune to the christian mystical experience.

There are earlier exceptions with the Baptists. The noted historian, Jane Shaw, would disagree that Baptists were definitive cessationists. She believed that new divine healings were occurring amongst the Particular Baptists though cautiously expressed. Further details or what epoch the Particular Baptists were operating are not known at this time.11 An 1883 edition of the Presbyterian Review disagrees with a protestant minister named Rev. A. J. Gordon, a Baptist writer, preacher and composer from Boston, who wrote a book called, The Ministry of Healing, Or, Miracles of Cure in All Ages. He argued miracles from the Moravians, the Huguenots, the Covenanters, the Friends, Baptists, and Methodists were still happening.12

The largest present religious training institution for Baptists is The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. This institution does not have any reference to cessationism in their doctrinal statement. However, within the Southern Baptist community there is some type of oral commitment to cessationism. One clue is from the Southern Baptist Convention. They recently changed their internal policy on speaking in tongues and now will give consideration to missionary applicants who do so. The previous policy outrightly rejected them.13

The Presbyterians

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, the bastion of american cessation belief belonged to the presbyterian theologians of Princeton Theological Seminary. This was especially found in the Principals of the Seminary; Charles Hodge (1797–1878), his son A. A. Hodge (Principal from 1878 to 1886) and Benjamin Warfield (Principal from 1887 to 1921). Warfield, in fact, is considered the last conservative leader of Princeton Theological Seminary.14

Charles Hodge, whom some have called the Pope of Presbyterianism15 was highly influential on the topic of cessationism—even though he never directly wrote on the subject. Being the principal and teacher of one of the leading theological seminaries during his era and a prodigious writer, Hodge helped establish and shape conservative American Protestantism for generations. Cessationism by his time was already lodged deeply within the Reformed psyche and needed no explanation. Neither was this an open topic for discussion. This left Hodge leeway to move into other theological topics, especially the encroachment of rationalism on the traditional protestant faith. Charles Hodge excelled at this because his large and comprehensive education demonstrated a well-rounded understanding of the rationalistic spirit of his times.16

After his death, the leadership torch of Princeton was passed on to his son, Archibald Alexander Hodge. Archibald similarly attacked the tenets of rationalist christian thinking rather than defend traditional protestant doctrine. Just like his father, he didn’t need to defend his faith because that was already stated and needed no revision. His coverage can be found in A Commentary on the The Confession of Faith. With Questions For Theological Students and Bible Classes, which was published by the Presbyterian Board for the purpose of teaching “theologians, Bible-class scholars, ruling elders, and ministers”.17 The semantics and logic contain a high degree of difficulty. He slightly altered the cessationist formulation in his approach, choosing the word revelation over miracle. Revelation is God expressing His divine will through miracles, the supernatural, act or order of nature. It is a more comprehensive word than miracles.

The order of miracles according to A. A. Hodge is too ambiguous to use in the cessationist clause, but there is an admission by him that miracles do exist, but veiled it in wordiness. He understood miracles as part of a comprehensive order of life that were “fixed in their occurrence by God’s eternal plan” and the “order of nature is only an instrument of the divine will, and an instrument used subserviently to that higher moral government in the interests of which miracles are wrought.”18 These are deep and complex thoughts that are almost cryptic. A. A. Hodge was attempting to work around the cessationist tenet that miracles cannot occur after the establishment of Scripture. He knew that miracles could occur today, but how could he manage an explanation without changing the fundamental cessationist framework? He rationalized that any miracles subsequent to the foundation of Scripture was pre-ordained at the creation of the world and part of the course of nature built by God.

The pinnacle of cessationist theory is held in the name of the last conservative principal of Princeton Theological Seminary, Benjamin Breckinridge Warfield (1851–1921). Unlike the high semantics of Charles Hodge, and the middling ground of A. A. Hodge, Warfield used everyday language to express both that miracles stopped around 100 AD.

How long did this state of things continue? It was the characterizing peculiarity of specifically the Apostolic Church, and it belonged therefore exclusively to the Apostolic age—although no doubt this designation may be taken with some latitude. These gifts were not the possession of the primitive Christian as such; nor for that matter of the Apostolic Church or the Apostolic age for themselves; they were distinctively the authentication of the Apostles. They were part of the credentials of the Apostles as the authoritative agents of God in founding the church. Their function thus confined them to distinctively the Apostolic Church, and they necessarily passed away with it.19

Warfield’s work was not unique. He took from Conyer’s Middleton’s work, Free Inquiry and simply updated it. He cites his name over 23 times. Warfield correctly asserts about the power of Middleton’s argument:

After a century and a half the book remains unrefuted, and, indeed, despite the faults arising from the writer’s spirit and the limitations inseparable from the state of scholarship in his day, its main contention seems to be put beyond dispute.20

Warfield’s commendation about Middleton still rings true today. The traditional protestant community, including the present renewalist movements, have not engaged in the important debate that Middleton made popular. No person or group has reconciled it within a christian framework or outright refuted it. It is a tension that still remains.

Warfield spent more time on outlining the counterfeit miracles than explaining the nature and purpose of miracles. He was happy with his short definition that they ended before 100 AD.

He used his theological framework as a basis to attack the catholic history of miracles and many of the legends and myths surrounding them. This is a predictable Protestant approach to miracles. A notable section is his assessment of the protestant miracles; especially the Irvingites, the Christian Science movement, and faith healers.

He does not note any individual faith healers, but the most prominent one during his day, John Alexander Dowie, was opposed to physicians and medical assistance including pharmaceutical intervention. Dowie was so influential and popular that he built a city outside of Chicago and called it Zion. 6000 devotees initially settled there.21 The city still stands today, though its early foundational roots have been shaken off. The Holiness movement itself had its share of faith healers and those that promoted the great physician over human doctors and medicine.

Jon Ruthven, author of On the Cessation of the Charismata deeply delved into Warfield’s motivations. He believed that there were a variety of influences that pressed upon Warfield when he wrote his book Counterfeit Miracles — many of which were eroding the traditional base of Protestantism.22 An interesting factor that Ruthven noted was a personal one. Warfield’s wife was struck by lightning on their honeymoon and became an invalid for the rest of her life. Ruthven wrote that we can only speculate on the impact, but it must have been significant.23

After the death of Warfield in 1921, the traditional Princeton message lost its momentum and the Presbyterian Church was confronted with more pressing internal matters. The era of Presbyterian influence on the American religious conscience was in serious decline.

1920s to Today

Cessationism was found elsewhere in the religious American psyche. One of the more important guardians was Lewis Chafer. Chafer was originally a Congregationalist minister – another offshoot of the Church of England that subscribed to the Savoy Declaration of Faith and Order, 1658. This declaration reaffirmed the ceasing of the gifts. Chafer was known for two important features of American Christianity. The first one related to him being mentored by Cyrus Scofield, whose Scofield Reference Bible had a major influence on the spread of a distinct christian framework called dispensationalism. Although Scofield emphasized little on cessation in his work,24 the mere association with his stature gave Chafer a national audience. Secondly, Chafer helped form a christian higher education institution called the Evangelical Theological College in 1924, which later became known as Dallas Theological Seminary. As one of the dominant suppliers of higher education teachers and pastors for almost 100 years, their doctrinal stance has reached christian communities throughout the world.

Lewis Chafer himself held to cessationism,25 and this translated into Dallas Theological Seminary holding a similar position. Their doctrinal statement contains this certainty:

We believe that some gifts of the Holy Spirit such as speaking in tongues and miraculous healings were temporary. We believe that speaking in tongues was never the common or necessary sign of the baptism nor of the filling of the Spirit, and that the deliverance of the body from sickness or death awaits the consummation of our salvation in the resurrection.26

Dallas Theological Seminary’s wording of cessation is a polemic against the Pentecostal and Charismatic movements. The Holiness movement and its child progeny, the Pentecostals blossomed in the early 1900s with an emphasis on the restoration of the early church and miracles. This led to a revival in the cessationist doctrine to counteract them such as the above statement. Jon Ruthven observed this fact; “the advancing front of charismatic growth has precipitated showers of polemical books and tracts, virtually all of these reiterating this cessationist premise.”27

By no means is Dallas Theological Seminary the only one producing traditional christian leaders of the cessationist strain. There are others such as Moody Bible Institute,28 but the importance has quietly disappeared.

From my own observation as a Bible College graduate,29 cessationism is dying in traditional reformed background schools. Young Christians entering into higher education are predominately from a renewalist background (Pentecostals, Charismatics and Third Wavers) who believe in the perpetuation of miracles. The precipitous drop of enrollment in higher christian education institutions has forced many schools to be more flexible or drop this doctrine altogether.

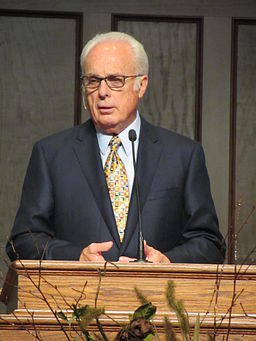

All contemporary discussions surrounding cessationism inevitably will lead to the strong opinions of the American radio host, church pastor, and author, John F. MacArthur. He may be one of the most controversial theological figures in the American christian community today.

Mr. MacArthur reaffirms the traditional reformed perspective on miracles. The only difference between MacArthur and his ancient Puritan influenced theologians is that he traded the virulent anti-Catholicism for anti-Charismaticism. Indeed, the parallels between the excesses found in mystic catholicism and the charismatic movements are very similar, and there are serious problems of credibility. He uses numerous examples of Charismatics to demonstrate miracles no longer exist and the acts they are performing are a sham.

His arguments are based on Scriptural references alone and there is no reference to the philosophical or rational attachments that have grown with the movement over the centuries. His message is simplified and intended for a mass audience. His approach and framework for writing on miracles is very similar to that of B. B. Warfield.

He makes the same mistake from the tradition instituted by the Protestants at the Reformation who threw out all catholic experiences related to miracles—not even giving it a status as myth or legend or even seeing the social context that framed such activities. MacArthur has simply changed the name of Catholicism to that of Charismatics and modernized the reformed script. This is reflected in his book, Strange Fire:

Charismatics now number more than half a billon worldwide. Yet the gospel that is driving those surging numbers is not the true gospel, and the spirit behind them is not the Holy Spirit. What we are seeing is in reality the explosive growth of a false church, as dangerous as any cult or heresy that has ever assaulted Christianity. The Charismatic Movement was a farce and a scam from the outset; it has not changed into something good.30

Much like the ancient Reformers before him, MacArthur points out some very real and tangible abuses in the realm of miracles, especially in the realm of faith healing. He takes such charges to the extreme and cites adherence to cessationism as a pillar of the true christian faith. On the other hand, the charismatic movement has become intransigent and refuses to make the necessary changes, just like the initial reaction of the medieval Catholic Church. This is history repeating itself.

You are at then end of this series. For the previous articles on this topic.

- Cessationism, Miracles, and Tongues: Part 1 Introduction and General Summary to this series.

- Cessationism, Miracles, and Tongues: Part 2 A medieval background to magic and miracle along with an overview of the Protestant view of miracles in the early church.

- Cessationism, Miracles, and Tongues: Part 3 The question of miracles from Martin Luther to the Church of England.

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/Methodism

- The More Excellent Way Sermon 89:2

- John Wesley’s Notes: Mark 16:17

- A Letter to the Reverend Conyers Middleton. Occasioned by his late Free Inquiry. January 4, 1748-9

- Transliteration as found at Craig L. Adams website, John Wesley and the Spiritual Gifts. The original text is found in An Earnest Appeal to Men and Reason and Religion by John Wesley. Pg. 41

- https://craigladams.com/blog/john-wesley-and-spiritual-gifts/

- Edward Irving. The Collected Writings of Edward Irving in Five Volumes. Gavin Carlyle ed. Vol. 5. London: Alexander Strahan. Pg. 479

- Edward Irving. The Collected Writings of Edward Irving in Five Volumes. Gavin Carlyle ed. Vol. 5. London: Alexander Strahan. Pg. 480

- on allowing unlicensed speakers and females to speak, allowing the church service to be interrupted on the Sabbath, and giving time in church for the expression of the gifts. Oliphant, Margaret. The Life of Edward Irving, Minister of the National Church, London. London: Hurst and Blackett, Publishers. 1862. Vol. 2. pg. 261

- Augustus Strong. Philosophy and Religion: A Series of Addresses, Essays and Sermons Designed to Set Forth Great Truths in Popular Form. New York: A. C. Armstrong and Son. 1888. Pg. 146

- Jane Shaw. Miracles in Enlightenment England. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. 2006. Pg. 49

- Marvin R. Vincent “Modern Miracles” as found in The Presbyterian Review Vol. 15. Charles A. Briggs, Francis L. Patton editors. New York: Anson D. F. Randolph and Company. 1883. Pg. 481 and see also A. J. Gordon. The Ministry of Healing, Or, Miracles of Cure in All Ages. London: Hodder and Stoughton. 1882. Pg. 78

- http://www.charismanews.com/us/49661-southern-baptists-change-policy-on-speaking-in-tongues

- https://www.theopedia.com/bb-warfield

- http://www.patheos.com/Resources/Additional-Resources/Presbyterian-Pope-Thomas-Kidd-01-04-2012

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Hodge

- A.A. Hodge. A Commentary on the The Confession of Faith. With Questions For Theological Students and Bible Classes. Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publication and Sabbath-School Work. 1869. Preface

- A.A. Hodge. A Commentary on the The Confession of Faith. With Questions For Theological Students and Bible Classes. Philadelphia: Presbyterian Board of Publication and Sabbath-School Work. 1869. Pg. 140

- B. B. Warfield. Counterfeit Miracles. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. 1918. Pg. 5

- B. B. Warfield. Counterfeit Miracles. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons. 1918. Pg. 31

- http://faith.galecia.com/essays/wolfe-dowie-zion-city

- Jon Ruthven. On the Cessation of the Charismata: The Protestant Polemic on Post-Biblical Miracles. 1993. Reprint 2008. Pg. 7 and 40

- Jon Ruthven. On the Cessation of the Charismata: The Protestant Polemic on Post-Biblical Miracles. 1993. Reprint 2008. Pg. 43

- “Tongues and the sign gifts are to cease, and meantime must be used with restraint, and only if an interpreter be present” http://www.sacred-texts.com/bib/cmt/sco/co1014.htm

- Lewis Chafer. He That is Spiritual. New Edition. Philadelphia: Sunday School Times Company. 1919. Pg. 57

- https://www.dts.edu/about/doctrinalstatement/

- Jon Ruthven. On the Cessation of the Charismata: The Protestant Polemic on Post-Biblical Miracles. 1993. Reprint 2008. Pg. 3

- https://www.moodyglobal.org/beliefs/sign-gifts/

- I attended Winnipeg Bible College which is now known as Providence University College and Seminary. At the time of attendance in the early 1980s the school had influences from Dallas Theological Seminary and Trinity Evangelical Divinity School. I must note unfamiliarity with the many and complex challenges facing christian higher education today and my comments may be based on trends and patterns of 30 years ago that have since been eclipsed by new issues.

- John F. MacArthur. Strange Fire: The Danger of Offending the Holy Spirit with Counterfeit Worship. Nashville: Nelson Books. 2013. Pg. Xvii.