722 B.C. The Assyrians conquered Israel and later Judah. Aramaic becomes the common language of the Israelites.

@460 B.C. Ezra brings Hebrew back as a religious language. The Aramaic Jewish audience hears the Jewish traditions but do not understand.

Hebrew

was entirely lost

as the mother

tongue.

Aramaic

Judaism created

many customs

around the

Hebrew language.

Afterwards, the Greeks ruled most of the known world. The Greek language became the international language of law and commerce. There was no escape from the Greek influence.

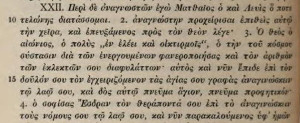

The Greek Jewish community adapted the Aramaic Jewish liturgy of instruction and/or reading in Hebrew with a spontaneous interpretation.

A conflict arose in Corinth over whether Doric (their native dialect), Attic, or Aeolic should be the standard Greek language for translation and other religious needs.

Speaking and interpreting was one of many issues confronting Paul while involved with the Messianic Jewish Community in Corinth.

Four Facts:

The synagogue act of public reading in Hebrew has evolved and is still in use today.

The relationship between the gift of tongues and the ancient Jewish liturgies are greatly overlooked in contemporary discussions.

Judaism discontinued the Hebrew instructor after 400 A.D. Christianity removed it from their customs around 100 A.D.

The use of an interpreter in both the Jewish and Christian liturgies were phased out in the Medieval Age.

The importance of the public reader, instructor, and interpreter were critical features of first-century Judaism. It is estimated only 10 to 15% of the people who lived in Roman Empire during this period were literate.

This interpretation framework believes that any miracle, including that of speaking in tongues, died with the early church and could never be repeated. Therefore, any research on the Corinthian tongues saga is only for historical purposes. The tongues of Corinth have no impact on the modern Christian life.

This interpretation framework believes that any miracle, including that of speaking in tongues, died with the early church and could never be repeated. Therefore, any research on the Corinthian tongues saga is only for historical purposes. The tongues of Corinth have no impact on the modern Christian life. Higher-Criticism is the dominant modern theory of explaining the tongues of Corinth and Pentecost. This doctrine believes that the christian rite of tongues has its origins with the Greek prophetesses at Delphi. These women performed inside a temple that had fissures underneath issuing volcanic fumes. The inhalation of the fumes would put the prophetess in an ecstatic state and would prophesy in what was believed to be unintelligible utterances. Ecstasy, glossolalia, and ecstatic utterance are keywords for this interpretational system. The higher-criticists supposed the earliest Christians synthesized this ancient Greek rite as part of making Christianity a universal religion. Church writings and ecclesiastical history are willfully excluded from this premise.

Higher-Criticism is the dominant modern theory of explaining the tongues of Corinth and Pentecost. This doctrine believes that the christian rite of tongues has its origins with the Greek prophetesses at Delphi. These women performed inside a temple that had fissures underneath issuing volcanic fumes. The inhalation of the fumes would put the prophetess in an ecstatic state and would prophesy in what was believed to be unintelligible utterances. Ecstasy, glossolalia, and ecstatic utterance are keywords for this interpretational system. The higher-criticists supposed the earliest Christians synthesized this ancient Greek rite as part of making Christianity a universal religion. Church writings and ecclesiastical history are willfully excluded from this premise.